I caved. Somebody sent me one of those time-wasting links you know you’re not supposed to click on if you want to get any work done. But I couldn’t help it. “Find out what your most used words on Facebook are,” the link said.

I was like Digory at the bell in Charn (for you Narnia fans). I had to know.

Plus, I had a feeling there would be a lesson about Bible study in it somewhere. So I did it. For you, dear reader.

And I am proud of the results, which you can see in the above word-cloud. The most prominent word on the Facebook account my wife and I share is “just.” Quite clearly, my wife and I share a concern for fairness, for justice. Our kids’ names are prominent, too, as are “love,” “good,” and “God”—which, interestingly, landed right next to “Bible” in the graphic.

This little scientific exercise, performed by an impartial computer, proves that our family is “just” and “good”; we “love” our “children,” our “Bibles,” and our “God.” It’s “sweet” and “cool” to be “us.” We’re “champion” “travelers” who “read” “new” “books” and are “happy” even in the “morning.” (And our “kids” “really” “enjoy” “bedtime.”)

Thanks to the clever algorithms behind this little tool, you don’t even have to read our Facebook postings. Just by counting words, you can know what we’re like, what we think.

Right?

Well, not exactly. Most of the words in the graphic are tip-offs to things we are, things we value (or “disagree” with, as in the case of “abortion”). I really am “Daddy,” and my wife really is “Mommy” (and “pretty”). But to know why all the words in that graphic are significant you have to know us. “Just” is so prominent not because we are so equitable but because we’re always reporting on Facebook what cute things our small children “just” did or said. (Real-life example from last week: “Our five-year-old just said, “I always have to be the peacemaker!”; and our four-year-old replied: “And I never get to!”)

The only people for whom this word-cloud could have any value are people who have read all our Facebook posts, but even then they’d have to know those posts pretty well to figure out what relationship these words—all ripped out of context—have to reality.

Do you see where I’m going with this?

Don’t just count your Bible; read it. Don’t use the powerful tools in Logos to help you ignore the contexts in which Bible words are used. Use those tools to provide new, fresh angles on those contexts—or, as we’ll see in a moment, to help confirm something that reading already suggested to you.

A bad example of word-counting

Let me give a bad example of word-counting in Bible study, then a good one.

If you have been in American Christian circles for long enough, you’ve heard that agapao (ἀγαπάω) denotes a volitional (will-based, non-emotional) love and phileo (φιλέω) denotes an emotional one. (I argued against this view briefly in a post on “What Agape Really Means.”)

Eugene Nida takes this view in a brief article in The Bible Translator. He acknowledges that agapao and phileo are “near synonyms,” and he thinks “it is a mistake to think of phileo as describing only human love and agape as relegated to divine love.” Both words, he says, “may describe very superficial and very profound types of love,” Nida suggests that the difference between the two in the NT instead “rests in the quality or nature of the love.”

What is that difference in quality, and how does he know? The one reason he gives in his article is essentially, “I counted”:

One important clue to the difference in the New Testament rests in the fact that nowhere are people commanded to love one another with the verb phileo, for phileo is not subject to command. It is the natural response of the heart . . . . The love of agapao can be commanded, for it consists in recognizing the value and worth in others.

“Difficult Words and Phrases,” The Bible Translator 3:3 (1952): 135.

In other words:

- phileo in the imperative mood in the NT = 0

- agapao in the imperative mood in the NT = 9

- Therefore, agapao is probably more volitional.

I have none of the well-deserved stature of Nida, but I’m afraid I cannot agree with him here. Both of these Greek words are used in contexts in which love is the natural response of the heart and contexts in which love is a recognition of the value and worth of others. (In fact, I would say that love is the natural response of the heart to value and worth of others—but the fall has twisted that response in all of us so that we no longer love what we should love and often love what we should not.)

Counting can take you strange places. Louo (λούω), meaning “wash,” never shows up in the imperative either—does that mean washing is not volitional? Or let’s take another pair of synonyms, chairo (χαίρω) and agalliao (ἀγαλλιάω), both of which are generally translated with the English root “rejoice.” Chairo appears in the imperative 17 times in the New Testament; agalliao occurs in the imperative only 2 times. Does that mean that chairo refers to a more volitional kind of rejoicing than agalliao?

Perhaps the love God commands—love for God, for neighbor, even for enemy—really is merely volitional, non-emotional. But we can’t know such a thing by word-counting, only by sentence-reading.

So are there any sentences in the NT—in the whole Bible—in which God reveals that the love he commands need not include emotions?

I do not believe so. In fact, the Bible says that one of the most prominent benefits of the New Covenant is that “the natural response of the heart” gets changed (Ezek. 36:26). We now love a God we hated (Eph. 2:11–18), and we “love the brethren” (1 John 3:14).

The word-counting approach can lead you astray. Sentence-reading always trumps it.

A good example of word-counting

But that doesn’t mean word-counting is worthless. Far from it. I genuinely and firmly believe that real insight can come from the use of concordances, word studies, and even vocabulary lists.

One of my old professors, Bob Bell, has many word-count tables in his book, The Theological Messages of the Old Testament, the culmination of 40 years of teaching Hebrew and Old Testament to students. He uses word-counting to help put on display themes or emphases in the text that he saw while reading.

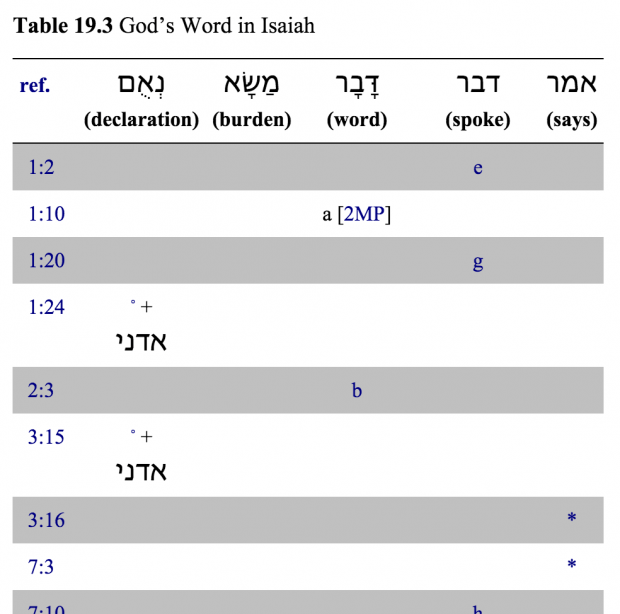

Let me give you an example. Bell includes one word-counting chart in which he shows the number of times Isaiah claims to be speaking for God. Here’s just a tiny portion of that chart:

If this chart doesn’t spur you to actually read Isaiah, it’s worthless. But it’s valuable if it makes you notice something in that reading that you didn’t before—that Isaiah’s prophecy is chock-full of claims that this prophet is speaking for God.

Why is this significant? I have in mind C.S. Lewis’ liar, lunatic, or Lord argument from Mere Christianity, transmogrified a bit to apply to Isaiah. Many people who read the Bible today think they are showing it respect by viewing it as the culturally constrained record of people’s experiences with the divine. They think of Isaiah’s prophecies as something we can all vaguely appreciate and honor, the way we all occasionally enjoy food from another culture. But—in the same way Lewis argued for Jesus’ divinity in his classic work—I argue that Isaiah has not left that option open to us.

Isaiah directly, explicitly, insistently, and—we can say because of word-counting methods—frequently claims to be the mouthpiece of God. He can’t be merely a nice religious man uttering nice religious platitudes. Either he’s lying, he’s crazy, or he’s really and truly speaking for the Holy One of Israel, the Lord of Armies.

Read

By all means, use the word-counting techniques enabled by Logos. Build a concordance of a biblical book using the concordance tool, run a search for the most common verbs in the Gospels, use the Bible Word Study’s connection to syntax searching to see the most common direct objects of the word “believe”—techniques pretty well unavailable to every previous generation of God’s people.

But use these word-counting methods carefully, and never as a replacement for reading, only as a support and a complement. Computers can count words. But only people can truly read them, interpret them, and be changed by them.

Now that you know how to use those word-counting tools responsibly, get them with our latest Logos version. Call our Resource Experts to find the Bible study resources that fit your study. Call: (888) 670-3148