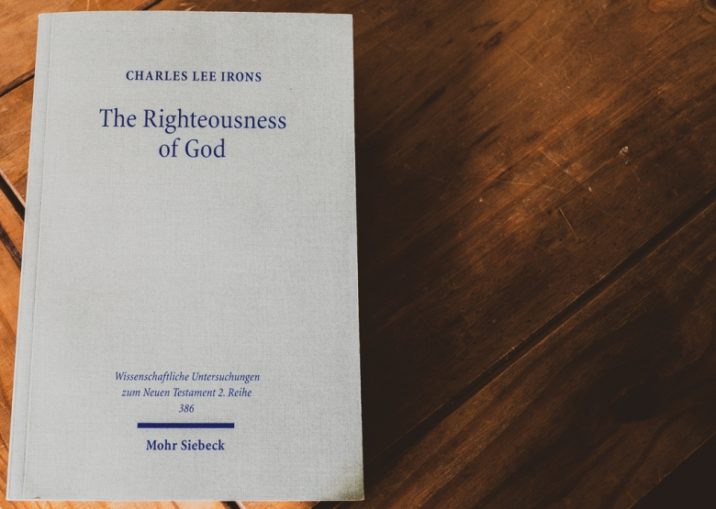

We recently had the opportunity to speak with Charles Lee Irons about his impressively researched monograph, The Righteousness of God (Mohr Siebeck, 2015). Lee offered some keen insight during our interview concerning the New Perspective on Paul, the use of “righteousness” language in the NT and surrounding literature, the subjective/objective genitive debate, and the significance of the “old perspective” for the health of the church.

What was your experience like working under the legendary Donald Hagner? Were you one of his last doctoral students at Fuller?

CLI: I was Don Hagner’s second-to-last doctoral student. Studying under Dr. Hagner was a pleasure. My favorite doctoral seminar with him was “The History of New Testament Research,” which provided a great introduction to the field and a general orientation to using a chastened historical‐critical method from a stance of faith. As a PhD supervisor, he was great. Even when he was traveling, he carefully read my chapters as I wrote them, quickly returning them with his corrections and comments. There were some points were we disagreed, but he always respected my freedom as a scholar and made sure I dealt with all the issues and secondary literature. What I appreciated most about Dr. Hagner was his balance of scholarship and piety. He believed in the historical-critical method, but he applied it in a reverent and believing spirit. He was totally conversant in the history of New Testament scholarship and the current literature, and yet he was a humble man of faith who revered the Scripture as the Word of God while also recognizing its human quality. As he liked to say, the Bible is the words of God in the words of men. See his contribution in I (Still) Believe: Leading Bible Scholars Share Their Stories of Faith and Scholarship (ed. John Byron and Joel N. Lohr; Zondervan, 2015).

You clarify early on that your intent is to address a shortcoming of the New Perspective on Paul, but you also make it clear that of the three pillars upon which the NPP is built, you only intend to address one. What are those pillars, and why did you choose to focus on Paul’s ΔΙΚ‐ terminology?

CLI: Scholarly paradigms like the New Perspective on Paul often have one or two major scholars who are the frontline spokespersons for the view, but what people don’t often realize is that there were antecedents that had prepared the ideological way for the new paradigm long before. So in the case of the NPP, the big names would be James D. G. Dunn and N. T. Wright. But the ideological ground had been prepared several generations earlier.

One of those who is rarely mentioned is the German theologian and lexicographer Hermann Cremer (1834–1903). He is more well-known for his Biblical‐Theological Lexicon of New Testament Greek, which was a precursor of Kittel’s Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (TDNT). Cremer set the stage for the NPP by arguing that “righteousness” in the Hebrew Bible is a relational concept. In other words, righteousness is the fulfillment of the demands of a specific relationship, and if the relationship is between God and man, then the relationship is a covenant. There is no norm external to the relationship that defines what righteousness is. The norm is the relationship itself. Cremer further argued that “the righteousness of God” in the OT is never a negative concept involving judgment or wrath but is always positive. He said it is a “thoroughly positive” concept, and therefore comes to be a synonym for salvation. For example, “In you, O LORD, do I take refuge; let me never be put to shame; in your righteousness deliver me!” (Ps 31:1). God’s righteousness is a saving righteousness. He saves or delivers his people in keeping with his covenant relationship with them. Thus “the righteousness of God” could be understood as his saving covenant faithfulness.

[callout img=”https://files.logoscdn.com/v1/files/28729067/content.jpg?signature=QMC3fJIrvIaKE9nA55lnvmkc2sc” text=”Get a useful resource for teaching Romans in the classroom with Zondervan’s” link_url=”https://www.logos.com/product/176894/reading-romans-in-context-paul-and-second-temple-judaism?utm_source=academic.logos.com&utm_medium=blog&utm_content=2019-05-30-interview-lee-irons-righteousness-of-god-mohr-siebeck&utm_campaign=promo-logospro2019″ link_text=”Reading Romans in Context: Paul and Second Temple Judaism”]

Another major precursor that paved the way for the New Perspective on Paul was Krister Stendahl. In a 1963 articled titled “Paul and the Introspective Conscience of the West,” he had argued that we need to reconceive Paul’s argument against justification by works within a sociological and covenantal frame. Luther and the Protestant reformers, he argued, mistakenly interpreted Paul through “the introspective conscience of the west,” as part of the quest to find how a sinner can relieve his sense of guilt and be right with God. Stendahl argued that this was a mistake, and that Paul’s doctrine of justification by faith had more to do with the Jew‐Gentile question and defining the identity of the covenant people of God. This new sociological approach lies behind the NPP. The NPP reinterprets Paul’s doctrine of justification by reframing the issue in terms of covenant.

The three pillars of the NPP are (1) E. P. Sanders’s revised view of Judaism as a nonlegalistic pattern of religion called “covenantal nomism,” (2) the argument that Paul’s polemics against “works of law” is not a critique of salvation by human effort but rather an attack on Jewish exclusivism and pride, so that the phrase refers to the Jewish boundary markers (circumcision, food laws, Sabbath) that distinguish Jews from Gentiles, and (3) the interpretation of Paul’s ΔΙΚ‐ language in covenantal terms, so that the verb “justify” means “to reckon someone to be a member of the covenant people of God” and the noun “righteousness” means “covenant faithfulness.”

I thought that the first two pillars of the NPP had been adequately addressed by critics of the NPP, but the third pillar had not been explored in as much depth. I chose to focus on the noun “righteousness” rather than the verb “justify.” I was particularly interested in Paul’s phrase “the righteousness of God,” which N. T. Wright (indirectly influenced by Hermann Cremer through Ernst Käsemann), interpreted to mean “God’s covenant faithfulness.” Ever since the debate between Käsemann and Bultmann in the 1960s over “the righteousness of God,” a lot has been written on this topic. I knew I would not be at a loss for secondary literature to interact with. I thought I had something unique to contribute by going back and doing the lexical spadework of studying the noun “righteousness” in both the Old Testament (in Hebrew and in the LXX) and the New Testament.

What I found interesting about your study was its methodology, especially your focus on the use of ΔΙΚ terminology in the LXX and your understanding of the Cremer Theory. What is special about your study of the righteousness of God in terms of methodology that potential readers and students of Paul should be aware of?

CLI: My methodology in critiquing Cremer involved a combination of lexical semantics and Septuagint studies. Cremer and all those who have been influenced by him argued that the Greek word for righteousness (δικαιοσύνη) was really a Greek word with a Hebrew meaning. Because the Greek word was used as a stereotyped rendering of the two Hebrew nouns for righteousness (tsedeq [masc.] and tsedeqah [fem.]), the Greek word could be understood as a calque with a specialized Hebraic meaning. This can happen—the classic example is the Greek word διαθήκη. In the LXX it is a stereotyped equivalent for the Hebrew word berit (“covenant”). The extrabiblical meaning “will or testament” is still possible and surfaces occasionally in the NT (e.g., Heb 9:16‐17), but by and large in Jewish literature composed in Greek and in the NT it means “covenant.” But in order to demonstrate that a word has become a calque, the acid test is to find examples where it is used that way in texts composed in Greek rather than in texts that are Greek translations of an underlying Hebrew text. I argued that there is no evidence that the Greek word for righteousness shifted from a norm concept to a relational concept (“covenant faithfulness”) under the influence of the Hebrew vorlage of the LXX.

[callout img=”https://files.logoscdn.com/v1/files/22450684/content.jpg?signature=Zt8qjXWdrmWCZFBOOhqtthNoLlY” text=”What are the implications of the NPP for ethics and mission?” link_url=”https://www.logos.com/product/174829/the-apostle-paul-and-the-christian-life-ethical-and-missional-implications-of-the-new-perspective?utm_source=academic.logos.com&utm_medium=blog&utm_content=2019-05-30-interview-lee-irons-righteousness-of-god-mohr-siebeck&utm_campaign=promo-logospro2019″ link_text=”The Apostle Paul and the Christian Life: Ethical and Missional Implications of the New Perspective”]

From Cremer on, it has been argued that “righteousness” in Hebrew thought is fundamentally different from “righteousness” in Greek thought. For example, Dunn wrote that “In the typical Greek worldview, ‘righteousness’ is an idea or ideal against which the individual and individual action can be meaured … In contrast, in Hebrew thought ‘righteousness’ is a more relational concept” (The Theology of Paul the Apostle, 341). There are some specialized usages that are unique to Hebrew (like the plural tsidqot, “righteous deeds”). But one of my main points is to refute the alleged Greek vs. Hebrew dichotomy by showing that there is actually a high degree of similarity between both languages. In fact, “righteousness” in Hebrew has an even stronger judicial thrust than in secular Greek.

You take the reader through an impressive reading of multiple ancient sources that include references to the righteousness of God, from extrabiblical Greek to the Old Testament and into Jewish Literature, before engaging in a thorough exegesis of δικαιοσύνη Θεοῦ in Paul, especially Romans. Is there a consensus view of the meaning of the term across all these sources, or are they too diverse to make any certain claims?

CLI: There is too much diversity to be able to say that there is one consistent meaning across all these various sources. However, we can set some general paramaters. If we restrict ourselves just to the noun “righteousness,” it seems to have two broad meanings (with all sorts of particular usages, contextual modulations, and shades of meaning under each): a judicial meaning and an ethical meaning. The first meaning, the judicial one, is that righteousness is the quality of a judge in justly executing justice. The second meaning, the ethical meaning, is as an umbrella term for moral goodness with a focus on one’s dealings with one’s fellow man. I argue that the ethical meaning is a metaphorical extension of the judicial meaning. It is important to keep these two broad meanings in conversation with one another and not to see them as so rigidly distinct that we lose the judicial element even in the ethical usage.

The importance of this can be seen in a specific modulation of the second meaning in the literature of Second Temple Judaism, and that is the concept of “righteousness” as a status before God. Is this an ethical or a judicial usage? It is both. It is a more theologically focused extension of the ethical meaning. Someone who keeps God’s laws and is ethically righteous, has righteousness as a status in the eyes of God the judge. But that means God has pronounced a judgment on that person’s righteousness and so the judicial background enters into this ethical usage. Paul will argue that there is none righteous (in the ethical sense), but that God has provided righteousness as a gift to all who believe in Christ so that they are deemed righteous (judicial sense) in his sight. Steven Westerholm has a wonderful exposition of Paul’s contrast between “the righteousness of the law” (ordinary righteousness) and “the righteousness of faith” (which he calls extraordinary righteousness).

[callout img=”https://files.logoscdn.com/v1/files/28728964/content.jpg?signature=JT5AECLoziW9LKalrZsqvEqDfn0″ text=”Get the tribute to one of the foremost interpreters of Paul,” link_url=”https://www.logos.com/product/176895/studies-in-the-pauline-epistles-essays-in-honor-of-douglas-j-moo” link_text=”Studies in the Pauline Epistles: Essays in Honor of Douglas J. Moo”]

To return to the question, there are these two broad meanings—the judicial and the ethical. Positively, my thesis is that these are both based on understanding “righteousness” as a norm concept rather than a relational concept. Negatively, the main conclusion of my work is that Cremer’s relational theory that “the righteousness of God” in the Hebrew Bible is a “thoroughly positive” and non‐judicial concept that means “God’s saving covenant faithfulness” is simply not supported exegetically or theologically. He gave seven arguments for this interpretation, but I refuted them point by point (pp 131–177). See also Table 8, “Righteousness of God” in Hebrew Bible (“My, His, Your”) on pp. 178–181, where I show that the law court imagery is present in all 41 instances in the OT, and that “the righteousness of God” in the OT denotes God’s justice in executing judgment on the enemies of his people, thereby vindicating them.

Where does your study sit on the dichotomy between objective and subjective readings of the genitive?

CLI: To be technical, the terms “objective genitive” and “subjective genitive” don’t really apply in the debate over “the righteousness of God.” They should be reserved for cases where the head noun conveys a verbal idea, which then permits one to take the head noun as either the subject or the object of the implied verb.

For example, “the love of God” could mean either “God’s love for us” (subjective genitive) or “our love for God” (objective genitive). The phrase δικαιοσύνη Θεοῦ does not contain a verbal idea, so it is not appropriate to ask whether “God” is the subject or the object of the implied verb. Despite this, in the literature there is a debate whether “of God” is an objective or a subjective genitive. The so‐called objective genitive interpretation is that it refers to “a righteousness that God approves.” Calvin held this view, but it is not widely held today. The so‐called subjective genitive interpretation is that “righteousness” is a verbal idea, so that the whole phrase could be translated “God’s saving activity,” God being the subject of the verbal idea of salvation.

I’m not persuaded by this proposal. Many scholars influenced by Cremer have argued this based on the passages in Isaiah where God’s righteousness and God’s salvation are found in Hebrew parallelism (e.g., “My salvation is about to come; and my righteousness is about to be revealed,” Isa 56:1; cp. Isa 45:8, 21; 46:12‐13; 51:5, 6, 8). But as I argued in the book, that is not the way Hebrew parallelism works. It almost never means that the two members of the parallelism are perfectly synonymous. Usually the second line adds something new to create a composite idea. James Kugel explained this using the formula, “A, and what’s more, B” (where A and B refer to the first and second members of the parallelism respectively). In this case, the composite idea is that God’s deliverance of his people comes through his righteous judgment on their enemies. Furthermore, to argue that “God’s righteousness” in Greek can mean “God’s saving activity,” one would need to find evidence of this usage in Jewish literature composed in Greek.

The phrase δικαιοσύνη Θεοῦ (or Θεοῦ δικαιοσύνη or δικαιοσύνη αὐτοῦ) occurs 10 times in Paul’s writings. I argue that in 7 of the occurrences (Rom 1:17; 3:21‐22; 10:3 [2x]; 2 Cor 5:21; and Phil 3:9) the phrase denotes a righteousness from God as a gift, taking Θεοῦ (“of God”) as a genitive of source or author. The other 3 occurrences (Rom 3:5, 25‐26) signify God’s distributive justice, and then Θεοῦ would be a genitive of possession. The NPP interpretation, “God’s covenant faithfulness” is not found in any of the 10.

After reading your work, what should the reader conclude about the theological implications of adopting the NPP view of the “righteousness of God” and its emphasis on covenantal categories of interpretation?

CLI: I have mounted a critique of Cremer’s relational theory of righteousness and its exegetical offspring, the covenant‐faithfulness interpretation of “the righteousness of God” in Paul, which is a key component of the NPP. I realize these are widely held views, and that I am going up against some of the titans of biblical scholarship in the 20th century. Almost all of the lexicons of biblical Hebrew and Greek and the major theological dictionaries assume and promote Cremer’s relational theory. It is a deeply entrenched position in both Old and New Testament scholarship. Such a monolithic view will not die out easily or quickly. But my hope is that I have raised some serious challenges to that view.

[callout img=”https://files.logoscdn.com/v1/files/21587236/content.jpg?signature=hgas5Khn-SGO2lE0rY7zxAdmurU” text=”Justification by faith alone was a Reformation rallying cry, and is” link_url=”https://www.logos.com/product/172376/the-doctrine-on-which-the-church-stands-or-falls-justification-in-biblical-theological-historical-and-pastoral-perspective” link_text=”The Doctrine on which the Church Stands or Falls”]

What is the value of your work for the church, and why should pastors and seminary students be familiar with your work in The Righteousness of God?

CLI: Although the heat of the debates over the New Perspective on Paul seems to have died down, and many have pronounced a desire to move beyond the New Perspective, there remains a lingering doubt that perhaps Luther wrongly read Paul through the lens of “the introspective conscience of the West.” N. T. Wright says Paul’s doctrine of justification isn’t about how to get your sins forgiven so you can go to heaven when you die, but about defining who the people of God are. Justification by faith means all who wear the badge of faith, whether Jews or Gentiles, are reckoned as members of the covenant. The righteousness of God isn’t a gas that floats through the courtroom and is transferred from the judge to the defendant, but God’s faithfulness to his covenant with Abraham which promised a worldwide people of God that included Gentiles.

Because of the wide impact of the NPP, especially through the prolific writings of N. T. Wright, there is confusion over Paul’s doctrine of justification. I hope my work has given new life to an “old perspective,” Reformation reading of Paul. Clearly, “the righteousness of God” was an important, even crucial, concept for Paul. He talks about it right at the outset of his epistle to the Romans as something that stands at the heart of the gospel (Rom 1:16-17; 3:21-26). Paul stated that the gospel is the power of God unto salvation because in it “the righteousness of God” is revealed by faith.

For Paul, this teaching of righteousness by faith stands at the heart of the gospel. He believed and taught with all his energy that the only way sinners can have a status of righteousness before God is not by doing what the law requires, since no one does keep the law, but by grace through faith in Christ. Thanks be to God for “the free gift of righteousness” (Rom 5:17)!

Read further into the debate over God’s righteousness at the scholarly level with the heavy-duty, 15-volume Mohr Siebeck Perspectives on Paul, Judaism, and the Law.

Pre-order now, and save $500 off the retail value through Pre-pub.