This is a guest post by Dr. Craig Evans, the John Bisagno Distinguished Professor of Christian Origins at Houston Baptist University.

When the Roman authority in Jerusalem crucified Jesus, who was viewed as a dangerous messianic pretender and disturber of the peace, there was no uncertainty about what came next: The body of Jesus would be buried in a tomb, but not in a place of honor. That was the Jewish law, and the Romans had no objections to it.

We know the Romans permitted the Jewish people in Israel to follow their customs. If they had not, they would have had insurrection on their hands. Proper burial of the dead, even the bodies of the executed, was of enormous importance to the Jewish people. Guided by the Mosaic law of Deut 21:22–23, the Jewish people buried the dead before nightfall to safeguard the purity of the land. This included criminal dead. We also know that this Jewish custom was respected by the Romans, during peacetime (as seen in Philo, Embassy 300 ; Josephus, J.W. 2.220; Ag. Ap. 2.73), especially because of what Josephus reports: “the Jews used to take so much care of the burial of men, that they took down those that were condemned and crucified, and buried them before the going down of the sun” (J.W. 4.317).

Moreover, even Roman law itself permitted burial of the executed, if petition was made to the authorities (Digesta 48.24.1–3; where emperor Augustus is the cited authority). We know that Josephus was speaking of persons crucified by Roman authority (and not Jewish authority), because capital punishment was limited to Roman jurisdiction, which in first-century Israel meant the Roman governor (Josephus, J.W. 2.117 [“having the authority to kill put into his hands by Caesar”]; Ant. 20.200–203; John 18:31).

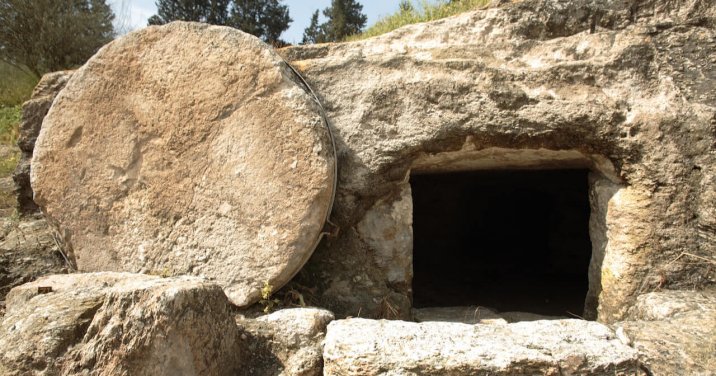

Accordingly, there is no reason to doubt that the body of Jesus was taken down from the cross on Friday and buried before sunset, as the New Testament Gospels tell us. In compliance with Roman law, Joseph of Arimathea requested permission to take custody of the body of Jesus (Matt 27:57–58; cf. P.Pintaudi 52; P.Oxy. 51; P.Oxy. 475; Digesta 48.24.1, 3). The body was not placed in the family tomb or another tomb of honor, for Jewish law did not permit it (m. Sanh. 6:5), but rather it was placed in a tomb not yet in use (Matt 27:59–60; cf. Semahot 13.7). This was an extravagant act of mercy on the part of Joseph.

The Gospel narratives are consistent with the relevant ancient literature and archaeological data, both Jewish and Roman, both Palestinian and elsewhere in the empire. That the body of Jesus was taken down from the cross and placed in a known tomb, under the direction of someone acting on behalf of the Jewish Sanhedrin, should be accepted as historical.

Why did the women visit Jesus’ tomb?

So if the body of Jesus received proper burial late Friday afternoon, why did women visit his tomb early Sunday morning? The Gospels tell that the women brought spices with them (Mark 16:1; Luke 24:1). They did this because of the Jewish custom of visiting the tomb of the recently deceased every day for one week (Josephus, Ant. 17.200; Semahot 12.1; cf. Gen 50:10; 1 Sam 31:13). This was primary burial, or the first funeral, as it were. The spices and perfume helped mask the unpleasant odor of the decomposing corpse. One year later, as prescribed by Jewish custom (b. Qiddushin 31b), family members gathered up the skeletal remains and placed them in a niche, or in an ossuary (m. Sanh. 6:6; Semahot 12.9). In the case of one executed, the remains were collected from the burial place of shame and placed in the family tomb or other place of honor (m. Sanh. 6:5–6; Semahot 13.7). The belief was that after one year of death, and the consequent wasting away of the flesh, removed the stain of guilt.

According to the Gospel of Matthew, the tomb of Jesus was sealed, which made it clear that his body could not be removed and placed elsewhere. The famous Nazareth burial inscription (SEG VIII 13) is probably relevant here. Tampering with tombs was a serious offence. If such happens, Caesar orders that charges be laid. However, visiting the tomb of an executed criminal and weeping quietly were permitted (m. Sanh. 6:6). This is what the women plan to do, so they wonder who will assist them in moving aside the heavy stone (Mark 16:3), that they might enter the tomb, anoint the body of Jesus, and silently pray and grieve.

As it turns out, all of their preparations and plans were thrown to the wind. When they arrive at the place of burial, they find that the stone has been rolled aside and there is no body of Jesus to be anointed. There will be no one week of private, quiet mourning. What has happened? It is probable that they assumed that the body of Jesus had been removed by the Jewish authorities, perhaps on the grounds that the body should have been placed in tomb previously used and designated for the burial of the executed. Perhaps the kindness of Joseph of Arimathea in making his not-yet-used tomb available for Jesus had been overriden by the high priest. It is not likely that the first thing that popped into the minds of the women was resurrection.

What persuaded the women, and soon after several of the male disciples, that Jesus had in fact been raised from the dead was not the empty tomb but actual appearances of Jesus to them. The appearances demonstrated that Jesus still lived; the empty tomb made it possible to speak of resurrection and not merely ghostly apparitions. After all, according to the Jewish understand, resurrection was the raising up of the dead from their dusty graves (as in Isa 26:19; Dan 12:2).

The appearances of Jesus, not only to disciples, supporters, and friends, but also to the indifferent and hostile, offer strong evidence that he had in fact been raised from the dead, that the Easter proclamation was not a hoax or silly urban legend. The resurrection of Jesus, which includes the story of his death and burial, is consistent with all known evidence and makes very good sense of the narratives that the four New Testament Gospels give us. It is therefore important to become familiar with the relevant background archaeology and literature.

***

Keep exploring the Easter story with Dr. Evans. Pick up his Mobile Ed course on Archaeology and the New Testament and The Bible Knowledge Background Commentary: New Testament (3 vols.).