The title thou hast lately read art not a clickbait and switch. Verily, I believe it to be one of truth and importance.

Let me put you at ease right away by telling you what I mean by it.

God did not say, “Thou shalt not steal.” He said “You shall not steal.”

He did not say, “I AM THAT I AM.” He said, “I AM WHO I AM.”

Jesus did not say, “Whosoever believeth in him should not perish.” He said, “Whoever believes in him should not perish.”

As linguist Steve Runge has often observed, “Choice implies meaning.” And the choice to use Elizabethan English today adds another message on top of whatever the Bible is saying—a message the KJV translators never intended. It says, “Behold! Thou art reading solemn, elevated, religious verbiage!”

For many people I respect, this elevation is a selling point for the KJV. But one major argument of my new book, Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible, is that the Spirit of God did not choose elevated, archaic, “religious” forms of Hebrew or Greek—and neither should we in English. When the Spirit of God inspired the Old and New Testaments, he used then-current Hebrew and Greek. In our Bibles we should use now-current English.

A new book on an old one

On the surface level, it isn’t hard to grasp what “Thou shalt not kill” means, so I am not saying that everyone should throw out their KJVs. I certainly won’t throw out mine—I use it every day in Logos. The KJV still has important and valuable uses. But when translating, reading, or teaching a text as important as the Bible, we have to be attentive to the language we use. What connotations do we add to the text when we use Elizabethan language in 2018?

As I point out in my new book, all native English speakers intuitively catch the strong overtones of religious authority that Elizabethan English now carries. When you use this form of our tongue, what you say feels, well, authorized. Why else would the Book of Mormon and the Pickthall translation of the Qur’an, published in 1830 and 1930, respectively, use thee and thou and -eth on the ends of verbs?

Here’s the Book of Mormon, with all the Elizabethan English bolded:

Holy, holy God; we believe that thou art God, and we believe that thou art holy, and that thou wast a spirit, and that thou art a spirit, and that thou wilt be a spirit forever. (Alma 31:15)

Here’s the Qur’an:

Verily there cometh unto you from Me a guidance; and whoso followeth My guidance, there shall no fear come upon them neither shall they grieve. (2:38)

These quotations may not sound odd to you. Maybe you expect religious talk to be vaguely otherworldly. But it is odd, historically speaking. It shouldn’t fit; it should feel like Shakespeare translated into Valley-girl. No one alive spoke or wrote Elizabethan in 1830 and 1930, so why did their particular form of English, one that flowered mostly in the 1500s, become the “religious” English? Why wasn’t it the English of the 1300s, or the 1800s? The English of every century is recognizably distinct. Jane Austen’s prose will never be mistaken for Winston Churchill’s, or vice versa. It’s just an accident of history that Elizabethan English has the meaning it does for us.

An accidental sanctity

It’s obvious how the accident happened. The King James Version has exercised a massive influence on our speech—and even our cultural psyche.

I’m not too upset about this; this was in many ways a good accident. KJV English is very beautiful to many, and its phrases have leavened the English loaf in wonderful, fragrant ways. My book opens with a full chapter acknowledging the valuable things we lose as the KJV slips from its position of dominance; its elevated, archaic beauty is one of them.

But KJV English has what C.S. Lewis called “an accidental sanctity.” It didn’t sound antiquated or religious to its original hearers. It was just the way people talked. But as the way people talked (and wrote) changed, KJV wording began to gather religious-y overtones its translators couldn’t have known to expect. Even by the time of the first major English lexicographer, Samuel Johnson (1709–1784), King James English had become “solemn language” (Johnson’s wording), something recognizably distinct from normal English.

KJV Readability

These sanctified overtones have left us with a situation in which KJV English gives a certain air to God’s speech that he, like the translators, never intended. And the process of change in English has caused some serious problems for readability—at least for those people who didn’t grow up speaking Elizabethan English. And, given that the oldest human now alive was born multiple centuries after everyone stopped speaking this way, I think it’s safe to say there’s nobody left who speaks native KJV.

Readability isn’t yet something computers can truly measure (I have a whole chapter explaining why in my book); it’s not the kind of straightforward, mathematical activity computers comprehend. Written language has so many elements, and every one of them contributes to readability in profound ways. Computers can count word and sentence length, yes. But punctuation, word choice, syntax, and even formatting have an impact on the reader’s experience, and computers have a much harder time gauging these. A computer doesn’t know that righteousness is actually an easier word than caul, or that a semicolon and a colon can be powerful tools for meaning. Computers can’t “understand,” they can only count.

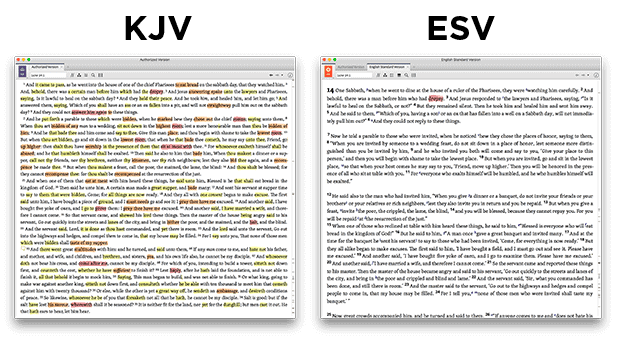

If you marked up a random chapter of the KJV like an editor would, highlighting all its differences from the way we would write today, you’d get something like the colored “heat map” below (taken from Authorized).

- Yellow means something pretty easy to understand.

- Orange means something that might trip up readers.

- Red means something that today’s readers will almost certainly misunderstand—through no fault of their own, but merely because of the inevitable process of change in English.

To be fair, I did the ESV, too—it’s on the right.

Other things being equal—and they generally are, because we have so many good Bible translations—a translation that uses modern English is going to be easier than one that doesn’t.

I am not criticizing the KJV; in the book I say not one negative word about the decisions of the KJV translators. I think their work was sterling. I’m not nearly as smart as they are; my only advantage is that I happen to be breathing. I speak today’s English. They didn’t. If English continues to change at the rate it has been for the last few centuries, the ESV and NIV and NLT and all of today’s translations that speak my English will start gathering yellow, then orange, then red highlights, too. It is no one’s fault that language changes. Authorized argues, however, that we have a moral obligation to change with it. The Bible’s message is too precious—we can’t let any other messages compete with it.