The last few years have been a pretty sensational time for textual criticism of the Bible. You might think that the level of excitement in this tiny scholarly world can’t possibly get that high. But you’d be wrong. Don’t believe me?

Consider a few examples: A world-renowned scholar was arrested on suspicion of stealing over one hundred Greek papyri from the Sackler Classics Library in Oxford for sale on the black market. A years-long academic brouhaha over a supposed “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” in Coptic was exposed as an elaborate hoax on par with daytime soap opera plots. Fragments of an extraordinary paleo-Hebrew scroll that came to light in the 1880s—but that were quickly dismissed as a forgery and then lost— were recently proclaimed as authentic after all.

All of this activity (and more) has occurred within just the last 12 months or so. As if that wasn’t enough, just in the last few weeks, even more exciting news broke in Israel that has plenty more to offer those interested in the text of the Bible—especially the Septuagint.

Looters, caves, and a Neolithic basket

Since 2017 the Israel Antiquities Authority has been working with unprecedented fervor to find and preserve ancient artifacts in the Judean Desert before looters do. So far the renewed effort to scour and excavate caves scattered throughout the Judean Desert had paid off in astounding ways. Among the latest discoveries, for example, is a massive and fully-intact basket that was found in the area around Wadi Muraba‘at. The basket is over 10,000 years old. Let that sink in—it’s older than the invention of ceramic pottery itself.

Other remarkable finds include a 6,000-year-old mummified child, a cache of Jewish coins from the Roman era, potsherds, and arrowheads. As amazing as these finds are, most exciting for textual scholars is the discovery of new manuscript fragments of the Bible—a few dozen of them to boot.

Sheer cliffs, human skeletons, and a French Catholic scholar

Part of what makes these new textual fragments so exciting is that they were excavated from the so-called Cave of Horror, which was discovered by (some very daring) Bedouins in the 1950s. That cave—less dramatically known as “Cave 8″—is precariously situated a few hundred feet off the side of a sheer cliff in the Naḥal Ḥever wadi.

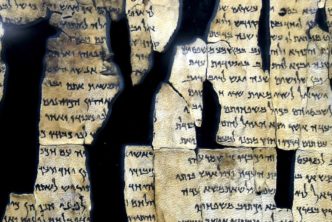

Originally, Cave 8 contained over 40 human skeletons (hence the colorful nickname) that once belonged to Jewish refugees who hid there during the tumultuous Bar Kokhba revolt. But the Cave of Horror also contained a scroll of the Minor Prophets in Greek, now known simply as the Minor Prophets Scroll, or by the less-than-user-friendly label 8ḤevXIIgr. The scroll was discovered by Yochanan Aharoni and later studied in detail by Dominique Barthélemy (1921–2002).

What makes 8ḤevXIIgr so significant is that the Greek text of the Minor Prophets that it preserves differs in certain ways from what we have in the Hebrew Masoretic Text, itself the textual basis of most modern translations of the Old Testament. In his seminal monograph Devanciers d’Aquila (Cerf, 1963), Barthélemy examined 8ḤevXIIgr and permanently altered scholarly understanding of the textual history of the Septuagint.

Prior to Barthélemy, scholars had noted similarities in various translation features between Judges, Ruth, parts of Samuel and Kings, and Lamentations. Of particular importance is the use of καίγε to translate the Hebrew וגם, an observation that goes back to Thackeray and which later became known generally as the Kaige Recension.

In Barthélemy’s study, however, he showed that this tendency was even broader and earlier than Thackeray (or anyone else) knew. Barthélemy added into the group books like the Song of Songs, the Theodotionic version of Daniel, the recension of Aquila, and some other texts.

The critical point was Barthélemy’s explanation of how all these texts tied together. How do you connect figures like Aquila with translation features in parts of Samuel and other books too? Answer: 8ḤevXIIgr. Barthélemy found the same kinds of translation tendencies in 8ḤevXIIgr that Thackeray and others had noticed in other places, indicating that the Kaige phenomenon was much broader and earlier than scholars ever thought.

Not only that, but Kaige features were not indicative of a totally new translation inserted later (as Thackeray thought), but rather according to Barthélemy, represented a revision of a Greek version already in existence. That revision was meant to bring the Greek version closer into alignment with the Hebrew text and it set a kind of precedent for later work such as the translation style we find in Aquila.

Septuagint studies and the promise of further discoveries

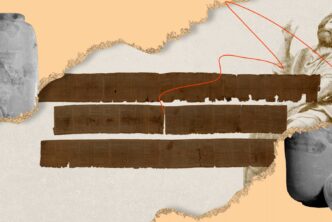

So what is the connection between Barthélemy and the recent discoveries? By all accounts so far, the new textual fragments announced just last month are part of the very same Greek Minor Prophets scroll that Barthélemy examined 60 years ago.

Now, it’s worth noting that they truly are fragments, only about the size of a mangled Post-It note at best. But the texts are nevertheless being studied carefully under the superintendence of Tanya Bitler, Oren Ableman, and Beatriz Riestra of the Dead Sea Scrolls Unit at the Israel Antiquities Authority. So far, eleven lines of Greek have been reconstructed from Zechariah 8:16–17 and Nahum 1:5–6 (in two different scribal hands), in which an example of the Tetragrammaton appears written in paleo-Hebrew.

So what do these new discoveries mean for Septuagint studies? It’s too soon to tell. But you better believe that these texts will receive a great deal of scrutiny in the years to come. For example, the Hebrew text of Nahum 1 has seen a good deal of scholarly argument over the years about its poetic features. The new Greek fragment from that chapter could very well shed important new light on the questions involved. Time will tell.

Whatever these new fragments may tell us, it most likely will not stop there. So far the Israel Antiquities Authority has surveyed over 500 caves using drones and rappelling equipment. But there are many more yet to be excavated. So from the sound of it, these recent textual discoveries will not be the last. It’s an exciting time in textual criticism indeed.

Related articles

- Do the Dead Sea Scrolls Answer the Canon Question?

- What Is the Septuagint and Is It Valuable for Bible Study?

- How to Compare the Septuagint to the Original Hebrew in Logos

- What Is the Talmud and Is It Beneficial for Christians?