The word “church” occurs only three times in the Gospel accounts, each time in Matthew. The most definitional of these uses comes from Peter’s confession of Jesus as the Son of God. Jesus replies to him,

And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it (Matt 16:18 ESV; emphasis added).

Of first importance, this passage teaches us that the Christian church is no ordinary institution of common interest, but that it is built by Jesus Christ himself. It is the only human institution that will endure into eternity, overcoming even the gates of hell, not because of its own human strength, but because Christ, the builder, sustains it.

The church is the people that Jesus came to save through his death and resurrection. Since the church is the redeemed people, where Christ has willed to dwell, the church is where salvation is to be found. “All who know God’s salvation know it as members of the body of Christ.”1

So then, what sort of a community is this people of God?

In this article, we’ll consider what the church confesses concerning itself, what Scripture teaches us to believe about the church, and what the church looks like now and can be heading into the future.

The church in its creeds

Ecclesiology is the study of the Christian church. The word ecclesiology derives from the Greek ekklesia, usually translated in the New Testament as “church.” Ecclesiology, then, encompasses what the Bible teaches about the church and one’s theological convictions concerning it.2

The doctrine of the church was important enough to the early Christians that they included its definition within their early creeds, alongside other important matters like the doctrine of the Trinity. The Nicene Creed, ratified at the Council of Constantinople (AD 381), expresses this baseline ecclesiology. In this creed, we confess “one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church.”

One

God’s people have real spiritual unity because we are all bound together by one Spirit, all redeemed by one Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, and all worship one God and Father of us all (Eph 4:4–6). The oneness of the church derives from and reflects the unity of Father and Son (John 17:20–23). Peter Leithart notes that humanity, though created to be one, was divided by sin. The church is the new humanity, reunited in God.3

Holy

God has set the church apart from the world (John 17:17–19). She is a people for God’s own possession (Titus 2:11–14), a temple of living stones, purified by the blood of Christ so that God may dwell in and with her. Because the church is the dwelling place of the Holy Spirit, the church is the place where salvation may be found.

Catholic

The catholicity of the church flows from its oneness.4 The whole church comprises all followers of Jesus, at all times, everywhere. Particular churches are manifestations of the one catholic church. The Christian believers worshiping in Indonesia, China, Africa, and Israel are your brothers and sisters. You will spend eternity with them. You are accountable to God for how you treat them. The church exists in the present as a visible institution, but it encompasses the whole of God’s people from all time—past, present, and future.

Apostolic

The faith of the church “was once for all delivered to the saints” by Jesus Christ through the witness of the apostles, and was faithfully handed down to subsequent generations (Jude 3). The church is founded upon that deposit of faith (Eph 2:19–22).

Related article: “To Creed or Not to Creed: Why You Need Creeds in the Christian Life” by Michael F. Bird

The church in the Bible

While creeds and Bible are not opposed, we have not arrived at a full account of what the church is until we’ve looked to what Scriptures say about it.

The church as an ekklesia

In the Greco-Roman world, the ekklesia could refer to an assembly of a city’s citizenry gathered to consider a course of political action.5 But is that how the New Testament writers would have used the word?

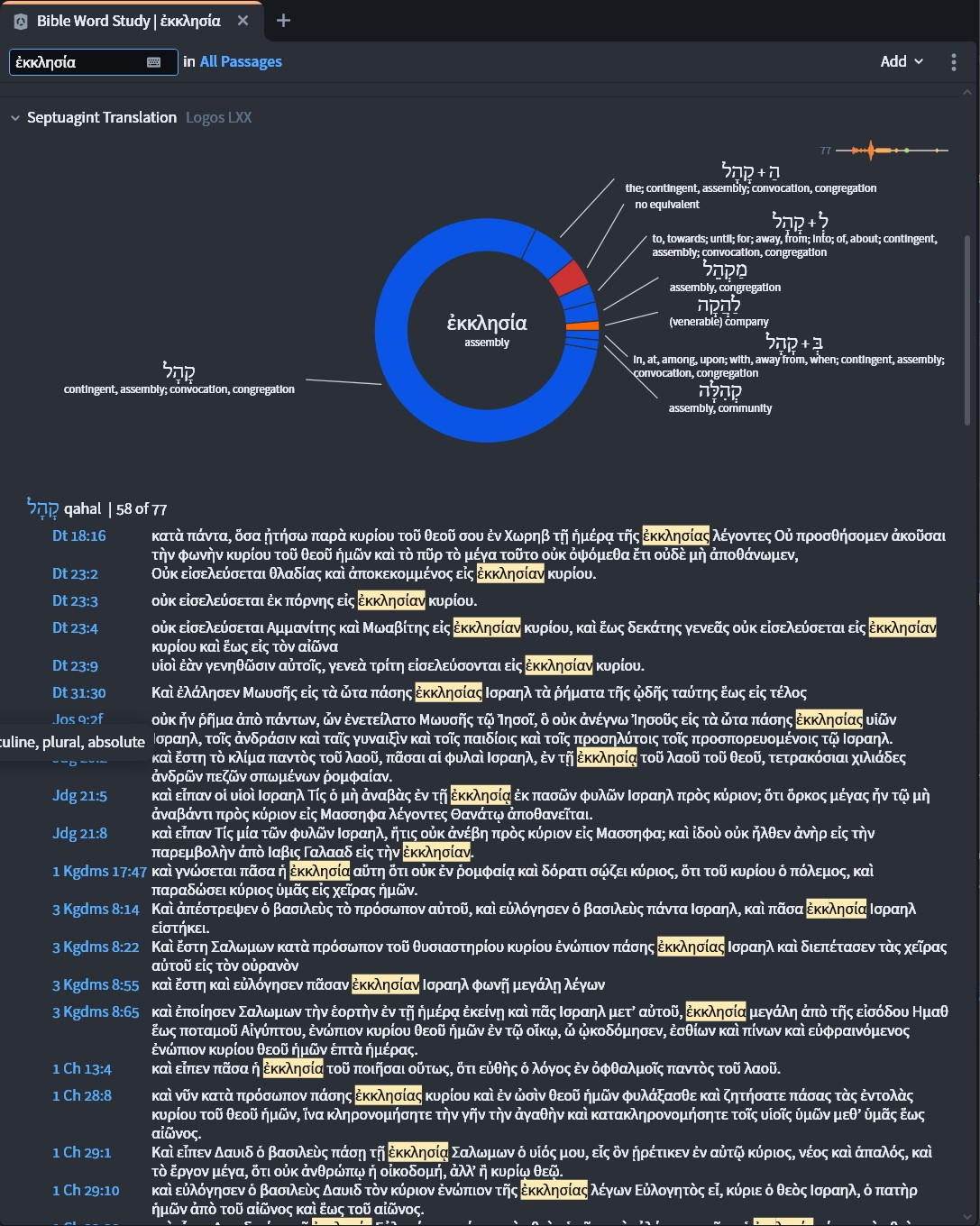

To determine this, we need to look at how ekklesia is used in the Greek translation of the Old Testament, often called the Septuagint or LXX. The Septuagint existed in the time of Christ and the apostolic writers and forms the background for the New Testament use of Greek vocabulary. We can easily examine the LXX’s use of ekklesia using Logos’s Bible Word Study combined with a tagged Septuagint. You can also refer to a Greek lexicon for a selection of usage.

Run a Bible Word Study on ekklesia in the Logos Bible Study app. Get the Logos app free, if you don’t already have it.

We find that ekklesia is most often used to translate the Old Testament word for Israel’s assembly (Hebrew qahal). This background helps guide our understanding of the meaning of its use in the New Testament

So does the New Testament use of ekklesia correlate at all with the Greco-Roman conception of ekklesia as a ruling or voting assembly? The Old Testament church (the assembly of Israel) was both a political and religious body. The nation had both civil and cultic aspects to it.6

If this is the background of the New Testament use of the word, the church in the New Testament must likewise be a politico-religious body.7

The church’s focus and mission has both vertical and horizontal dimensions. It has ultimate concern both with God and with fellow humanity. The political character of the assembly has not been nullified in the New Testament, even though the way the church relates to the civil realm has changed.

The ekklesia is the whole people of God, constituted by his Spirit. We see this first with Adam, humanity’s first representative, when God breathed life into his nostrils. At Sinai, Israel is formed as a covenant nation by God’s presence and residence in the tabernacle. At Pentecost, the Holy Spirit fills the church, making the very people his dwelling.

The church as a worshiping people

An important difference exists, however, between the church and the Greco-Roman assemblies. Greek assemblies gathered for civic functions, to advance political goals. They were not religious gatherings, as such.8

In contrast, the church’s highest and primary calling is to worship God. When the first century church gathered together in Jerusalem, it did so in order to devote itself to the apostolic teaching, to fellowship, to the breaking of bread, and to the prayers. Like the assembly of Israel, the Christian church is a community of faith. This is because this assembly is gathered not by an earthly city or state council, but by God himself.

This worshiping character is made clear in its designation as the temple where the Holy Spirit dwells (1 Cor 6:19). Because Jesus the cornerstone is the living stone, his people are also living stones being built up into a dwelling place for our God (1 Pet 2:4–5).

Like the priests of the Levitical order, Christ’s new royal priesthood must be cleansed of the uncleanness of sin to enter this temple (Exod 29:4; 30:19–21; 1 Cor 6:9–11; Heb 10:19–22). This is represented in the Old Testament through the many washings, and in the church as baptism. Christ washes us and then invites us into the presence of the holy Creator of the universe.

The church as a feasting people

If the church is a worshiping body, then, biblically speaking, it must be a feasting body as well. God’s assembly does not come together without eating and drinking.

YHWH commands Israel to appear before him when they have been established in the land, and to eat and drink (Deut 14:22–29). Notice that they are not simply to get together and have a feast, but to recognize and be mindful that they are doing it before his face. Their feasting is an act of worship. Because of this, they are not to treat it as their own meal, inviting only family and close friends. They are to show hospitality to the Levite, the orphan, the widow, and the sojourner (the foreigner dwelling with them)—the poorest among them.

So also with the church of Jesus Christ, Jesus invites us—commands us—to share a meal in his presence. In the Lord’s Supper, as the hospitable host, Jesus gives us the tokens of his body and blood, and says, “Take, eat, drink.” As with Israel, he is especially displeased when we treat this as our own meal (1 Cor 11:20–22). It is a meal of all God’s people. Not only does this meal express our unity, but it in fact constitutes and fosters it (1 Cor 10:16–17).

The church as body politic

While the worshiping and feasting character of the church are more easily recognized, its political character is more difficult, and perhaps even controversial, to navigate. So it warrants closer examination.

The church of Jesus Christ, as we have seen, is much more than the Greek notion of a city’s body politic. But it is not less. The very word “politic” speaks of a city. The book of Hebrews says of the Old Testament saints that Abraham and the patriarchs were “looking forward to a city” but did not in their life attain those promises (Heb 11:10–16). Of the heroes of the hall of faith, Hebrews says,

And all these, though commended through their faith, did not receive what was promised, since God had provided something better for us, that apart from us they should not be made perfect (Heb 11:39–40 ESV; emphasis added).

In contrast to those who only anticipated the fulfillment of the promises of God, Hebrews presents our arrival at the city of God as a present reality:

But you have come to Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and to innumerable angels in festal gathering, and to the assembly of the firstborn who are enrolled in heaven, and to God, the judge of all, and to the spirits of the righteous made perfect (Heb 12:22–23; emphasis added).

The church is the fulfillment of these promises, a city prepared by God to be far greater than the corrupt cities of man.

The church’s leaders as shepherd–kings

A city (polis) implies a polity—a structure of governance.

When we say “a pastor is a shepherd,” most accept this without objection. After all, that is the meaning of the word pastor. But what if we were to say that a pastor is also a ruler or king? That is more likely to raise some eyebrows.

Most of us are comfortable thinking of the office of “pastor” as something of a prophetic office, since pastors expound the Word and proclaim the gospel. Some Protestants may even dare to conceive of the pastorate as a priestly office, even if we do not hold to a continued distinct priesthood in the way the Roman Catholic Church does.9 We could argue that a pastor has both priestly and prophetic aspects.

However, the biblical concept of shepherd is actually more kingly than it is priestly or prophetic. In the Old Testament and ancient iconography, the shepherd’s crook is a feature, not of priests or prophets, but of kings. Who is the shepherd of Israel, the man after God’s own heart? Is he a priest, a son of Levi? No, rather, a king: David of the tribe of Judah.10 Yet David is not the ultimate king of Israel, but rules only under YHWH, the great Shepherd of Israel (Ps 80:1; 95:3–7).11

When Jesus says he is the good shepherd (John 10:11–14), this is a claim to kingship. Further, his identity as the great shepherd (Heb 13:20) identifies him as YHWH, the shepherd of Israel, who built his assembly at the rock of Sinai. So likewise, Jesus builds his assembly anew upon the rock of Spirit-filled apostolic confession (Matt 16:15–18).

When Jesus gives “pastors” to his church (Eph 4:11), he gives them as under-shepherds who ought to rule as he does. As church leaders in the city of God, his assembly, pastors are to labor under the rulership of our great shepherd, Jesus Christ.12

If pastor-as-king sounds oppressive or authoritarian to us, we must remember how Christ ruled and rules, and we should expect the same character of his under-shepherds. When Jesus’s disciples dispute with one another about which of them is the greatest, Jesus sets his own way of kingship before them as an example:

And he said to them, “The kings of the Gentiles exercise lordship over them, and those in authority over them are called benefactors. But not so with you. Rather, let the greatest among you become as the youngest, and the leader as one who serves. For who is the greater, one who reclines at table or one who serves? Is it not the one who reclines at table? But I am among you as the one who serves” (Luke 22:25–27 ESV).

When the apostle Peter echoes this exhortation to those he calls his “fellow elders” (1 Pet 5:2–4), he demonstrates that this shepherding function is not only for apostles, but for them as well (1 Pet 5:2–4).13

Pastors are called to judge the flock of God in the realms of doctrine and Christian practice, but they are to do so in a spirit of humility and service that reflects the gentleness of the King of kings. They must also vigorously defend the flock against heresy, sin, and attacking “wolves” (John 10:12; Acts 20:28–31; Rev 2:1–3). Jesus ruled by laying down his life for the sheep (John 10:14–15). Those who guard his flock must do the same (John 15:12–14; 1 John 3:16).

The church as an eschatological people

The church’s future (eschatology) is essential to ecclesiology. Although we now have access to the throne of grace and the presence of God through Jesus Christ, this is not the end. We have come to the heavenly city, but the city is not here fully realized. The present reality of our citizenship in God’s city must not lead us to an over-realized eschatology. Although we gather at Mount Zion, the city of God, we still look for the city that is to come. We have greater glory to look forward to (2 Cor 3:18).

Jesus has given his church a mission, and this mission implies an eschatology. He has commanded us to preach the gospel to every creature (Mark 16:15) and to make disciples of nations by baptizing them and teaching them to follow and obey Christ (Matt 28:18–20). To this end, the church is to make disciples of the nations, not only by winning converts, but by “teaching them to observe” Christ’s commands (Matt 28:20). The extent of Christ’s authority (“all authority”) defines the scope of our mission (“all nations”), and his presence with us is the guarantor of our mission’s success.

This eschatologically oriented mission carries political implications. Because God is the one who grants earthly rulers their authority (John 19:10–11; Rom 13:1–7; 1 Pet 2:13–17), part of the church’s mission is to call them to bow the knee to the King of kings (Rev 1:5; 17:14; 19:16). Describing his vision of the New Jerusalem, the apostle John says,

By its light will the nations walk, and the kings of the earth will bring their glory into it, and its gates will never be shut by day … They will bring into it the glory and the honor of the nations (Rev 21:24–26 ESV; see also Isa 60:3–5).

The church should call earthly rulers to lead their nations to walk by the light of the church and to add their glory to the heavenly city.14 Earthly rulers, converted by the gospel, should encourage their citizens to become citizens of the heavenly city, and the church must call them to rule consistently with the commandments Christ has given. Faith in Christ leads to obedience to Christ, not only for individuals, but for nations as well.

The peoples of all nations are to be incorporated into the church, Christ’s temple of living stones. When God promises to make Christ’s enemies his footstool (Ps 110:1; Acts 2:34–35), this doesn’t mean that he will trample all the nations into dust. Footstools are instruments of the king’s enthronement. The king’s feet gently rest upon a footstool—he does not break and crush it the way he crushes serpents.

David calls the ark of the covenant God’s footstool (1 Chron 28:2). And the Psalms identify the temple as YHWH’s footstool (Ps 99:5; 132:7). While YHWH’s glory fills the heavens, the train of his robe, where his feet are, fills the temple (Isa 6:1). To be made God’s footstool then is to be converted into his temple, a thing of honor.

Christ will reign until all things have been placed under his feet (1 Cor 15:25–28). This does not refer to mere conquest, but to the church’s mission to summon the whole earth to worship Christ, that at the name of Jesus every knee will one day bow and confess that he is Lord (Phil 2:9–11). Jesus is in the business of turning his enemies into precious stones in the city of God, his church. It is, after all, what he did for us.

All earthly governments will one day pass away and give way to the heavenly Jerusalem (Rev 11:15), for here we have no lasting city (Heb 13:14). At the final resurrection, Christ will deliver the kingdom up to the Father, having abolished every rule and authority and power (1 Cor 15:24). At that point, only the city of God will remain forever.

Thus, Christ demands that our primary allegiance be to his body politic (Phil 3:20). We are to embody now what is to be true in the future. When the laws of the city of man rebel against the commandments of God, we ought to obey God rather than men (Acts 5:29). We must seek to do good to all, but especially those who are of the household of faith (Gal 6:10). We seek the good of the city we are in because in its good we find our good (Jer 29:7). The good of the earthly city is not an end to itself, but a means to bless the people of God.

The church in contemporary practice

We have seen that church leadership must exist, but the proper form of that leadership is the subject of endless debate and division.15

Church polity (government) can be broadly categorized into three views, with variations depending upon the denomination.

1. Episcopalianism

Episcopal polity is a hierarchical structure of rule, consisting of bishops, presbyters (priests), and deacons. A bishop oversees a regional diocese consisting of many local parishes entrusted to priests and deacons. In some communions, dioceses may be organized into a larger jurisdiction, ruled by a metropolitan bishop. The whole communion may be ruled by patriarchs or a college of bishops. Episcopal ecclesiology sometimes includes the doctrine of apostolic succession, which teaches that the authority of the apostles (especially Peter) was passed down through a largely unbroken line to bishops of the present day.

Examples of episcopacy include the Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Anglican communions.

2. Presbyterianism

Presbyterian polity in its present form developed during the Reformation. Because of the abuses of the late-medieval church, Reformed churches were wary of conferring too much authority upon one person. A renewed emphasis on the priesthood of all believers furthermore led them to abandon priesthood as a distinct church office.

Reformed churches believe the Bible prescribes a more representative form of church government. Each local congregation is ruled by a session (its group of elders—both ruling lay elders and at least one teaching elder or pastor). Delegated members of the session participate in a regional presbytery body (classis in continental Reformed churches). Then finally, presbyteries are members of a larger global general assembly (or general synod).

3. Congregationalism

Congregational polity emphasizes the autonomy of the local congregation from any higher ecclesiastical government or authority. Although individual congregations may choose to associate with a larger group of congregations, no ruling body exists to which every congregation is bound to conform. Congregations may be led by a single elder or pastor, or by multiple elders.

Independent or non-denominational churches, Baptist associations, and free churches exemplify this form of ecclesiology.

Conclusion: Where’s our unity?

All proponents of these views are seeking to be faithful to the Scripture and the practice of the early church. Which one is correct? Is it possible that Scripture does not even prescribe a single form of church government, that multiple valid forms of ecclesiastical polity could exist? Perhaps.16

As we saw, Christians confess that the church is “one” and “catholic.” What, then, can we make of the divisions that we see among us? The answer must be found in the One who makes us one.

In the face of divisions, we must seek to witness together to the one who saved us and who offers salvation to the world. We must carry out the church’s mission to the world, calling nations to obey our Lord, conscious of our underlying spiritual oneness, even while real and visible divisions still exist.

All who confess the triune God have one root and one vine—Jesus Christ. We should recognize other branches who are attached to that same root. Like a tree whose trunk is obscured by a wall with only its various branches visible, Christ is often obscured from view by our division, with only our disparate denominations visible. Somehow, even with our diverse branches, we must present the root to the world.

How can we be one body when divided into denominations? It is hard to imagine how such deep rifts within the church can be healed. But Jesus is the great physician. He can heal his church, although that healing will probably look like nothing we expect. Toward that hope, we must recommit to those things that unite us: the apostolic faith of the Scripture and the sacraments of baptism and the Eucharist. We must not settle for an easy ecumenism, flattening out distinctives and adjusting to the lowest common denominator. Rather, we must strive for true unity rooted in God’s revealed will and character.

Most importantly, undergirding all our efforts must be a love for the brethren—we must want unity. We must earnestly desire and pray for it, just as Jesus asked it of his Father.

Recommended resources

The Temple and the Church’s Mission: A Biblical Theology of the Dwelling Place of God (New Studies in Biblical Theology, vol. 17 | NSBT)

Regular price: $19.99

Who Runs the Church?: 4 Views on Church Government (Counterpoints)

Regular price: $22.99

The Original Bishops: Office and Order in the First Christian Communities

Regular price: $54.99

Related articles

- Who Is Jesus? Answering Life’s Most Important Question

- Life Together, Confession Together: Why Churches Need Corporate Confession

- What Romans Teaches Us about Church Unity

- The Definitive Guide to Christian Denominations

- Edmund P. Clowney, The Church (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1995), 57.

- The English word “church” has a different etymology than the Greek word ekklesia. For a discussion on these differences, see my article, “Beyond ‘A People, Not a Place’: What the Church Really Is”.

- Peter J. Leithart, The End of Protestantism (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2016), 17.

- Lower-case “catholic” simply means “universal,” and does not refer to the Roman Catholic Church. When referring to the Roman Catholic Church, a proper noun, “Catholic” is capitalized.

- Karl Ludwig Schmidt, “Ἐκκλησία,” TDNT (Eerdmans, 1964), 530. It can also, less frequently, mean any group of people gathered together, even a mob (Acts 19:32).

- E. Benj. Andrews, “The Conception ΕΚΚΛΗΣΙΑ in the New Testament,” Bibliotheca Sacra 40.157 (1883): 40–42.

- As Clowney puts it, a “theo-political order.” Clowney, Church, 189.

- In a sense, the Greek polis had an unavoidably religious character, as did all cities of the ancient world, as do cities of any time or place for that matter.

- In fact, our word priest is derived from the Greek presbyteros, meaning “elder,” an office most Protestants see as continuing, while the word denoting the cultic office of priest is hiereus.

- Numerous examples also exists of Mesopotamian shepherd–kings and the Egyptian pharaonic iconography of the shepherd’s crook and flail. For more on shepherd–kings in the ancient Near East, see https://sumerianshakespeare.com/70701/502901.html.

- Daniel I. Block, The Gods of the Nations: Studies in Ancient Near Eastern National Theology, 2nd ed. (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 1988), 57–58.

- Peter J. Leithart, On Earth as in Heaven: Theopolis Fundamentals (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2022), 67.

- See also Augustine’s famous contrast between the two cities in City of God 14.28.

- The fact that the kings in this passage still have places of rule on earth and act in relation to the heavenly city suggests that this describes something happening during the church age, before the resurrection and consummation of history. Stephen S. Smalley, The Revelation to John: A Commentary on the Greek Text of the Apocalypse (UK: SPCK, 2005), 559).

- For a more detailed comparison of different church polities, see Paul E. Engle and Steven B. Cowan, eds. Who Runs the Church? Zondervan Counterpoints Collection (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004).

- Alistair C. Stewart, The Original Bishops: Office and Order in the First Christian Communities (Grand Rapids, IL: Baker Academic, 2014), 354–55. The Reformed Episcopal Church holds to this view.