The Orthodox Church, one, holy, catholic and apostolic, is present today on all the continents and, with its presence and apostolic labor, witnesses to the Gospel to all peoples, fulfilling thereby Christ’s command: “Go and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”1

What is the Orthodox Church? And how do Orthodox Christians approach the study of Scripture? For many believers outside of Orthodoxy, Orthodox Christianity seems exotic and foreign. But for believers inside her communion, she is sometimes called the Ark of Salvation, seen as the fullness of faith, the original Christian church, and the only sure place to find Christ. Due to this unique perspective, the Orthodox approach Bible study a little differently and have a unique perspective on many key doctrines of Christianity.

Table of contents

- Understanding the basics of Orthodox history

- Orthodoxy: A worldwide faith

- Orthodox faith is tradition

- So what are the core beliefs of this Orthodox tradition?

- Prominent Orthodox figures

- Deeper aspects of Orthodoxy

- Festivals and feasts of Orthodoxy

- How the Orthodox approach Bible study

- Embracing technology in Bible study

Understanding the basics of Orthodox history

Orthodoxy sees itself as the church of history. It sees itself not merely as an institution to join or a set of beliefs to affirm, but rather as the meeting place of God and the body of Christ. Archimandrite Vasileios wrote, “The Orthodox Church is not a religious view; it is a theophany, a manifestation of God.”2 The Orthodox Church regards itself as a living, breathing spiritual entity that carries this direct encounter with the love and wisdom of Jesus Christ forward through the ages.

Spiritual lineage

Orthodox Christians believe that their spiritual lineage traces back to the early Christian communities established by the apostles. The disciples of Christ who were sent out into the world to “turn the world upside down” with the gospel (Acts 17:6) found that their message was received in many places. So it was said that “it was in Antioch that the disciples were first called Christians” (Acts 11:26). As the gospel went out, particular churches were established in many parts of the world, some of which are mentioned in the New Testament—think of Corinth, Philippi, or Thessalonica.

This revealing of the church was—in the Orthodox view—carefully preserved through apostolic succession, the teaching that proper authority in the church comes from an unbroken chain of ordinations from the apostles to contemporary bishops; and, equally important, a simultaneous commitment to the Orthodox faith and to the teachings of the church. “The Apostles handed down to their successors that which they had received from the Lord: the same faith, the same Baptism, the same Holy Mysteries, the same Godly life,” say Bishop Danilo and Hieromonk Amfilohije in their catechism, No Faith Is More Beautiful Than the Christian Faith. “Their successors handed that down by the laying on of hands … to their successors, and these in turn to their successors.”3 This unbroken chain of faith and order from the apostles to today’s bishops is a key belief of Orthodoxy, providing the church as it does with a direct link to Christ and his teachings.

Worshiping faith

We call our faith “Orthodox” because the church endured many persecutions throughout history that posed a threat to the truth, including numerous theological debates and controversies. Literally meaning “right belief,” and alternatively translated “right glory,” Orthodox Christianity is a worshiping faith, grounded in the ancient Scriptures and the historic worship life and liturgical rites of the church.

It is a worshiping faith, and as dogmatic theology professor Harry Boosalis writes: “Indeed liturgical worship lies at the very center of the life of the Orthodox Church. To worship Christ remains the ultimate focus of Holy Tradition.”4 The worship of Christ is intimately linked with personal purification and our understanding of truth: “All the truths of faith … are only revealed to a prayerful mind and a pure heart.”5 In Orthodox perspective, sin can be a barrier to understanding and illumination.

Creeds and councils

Our commitment to Orthodoxy as “right belief” is most evident in our historical participation in the Seven Ecumenical Councils6 of the first millennium of Christianity. These councils, held between the fourth and eighth centuries, were pivotal in defining and defending the Orthodox Christian faith against emerging heresies.7 Attended by bishops from across the Christian world, these councils made significant decisions that are still important to Orthodox Christians today, and are part of the common inheritance of much of the Christian world.

Probably the most well-known statement to come out of these councils is the Nicene–Constantinopolitan Creed (also simply called the “Nicene Creed,” or the Creed, for short), which Orthodox Christians continue to proclaim in each Divine Liturgy. In unison, we say, “I believe in God the Father Almighty, maker of Heaven and Earth,” showing forth a living testament of faith, firmly uniting individual Orthodox Christians in a corporate profession of belief in God as revealed to us through the person and work of Christ, and ultimately to a revelation of God as eternal Trinity. To this day, Orthodox Christians recite the original, unaltered Creed of AD 381.8

Patriarchates

It’s important to note that at that point in church history, Christianity had begun to coalesce around ancient centers of faith, known in Orthodoxy as “patriarchates.” The unity of the Church across vast distances was preserved by organizing and consolidating territories under “patriarchs.” The rise of the five early patriarchates, known as the Pentarchy, enabled the unity of the church across vast distances, and were located in Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem. These centers of authority and spiritual leadership preserved the unity of the church through their shared faith and decisions in council.

The Great Schism

Tensions between the Patriarch of Rome (i.e., the Pope) and the Eastern Patriarchates led to a separation between East and West in the eleventh century, known as the Great Schism. Bishop Danilo offers this explanation:

Until that time not only the East but the West also belonged to the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church of Christ. The reason for the separation was the introduction of various innovations in the West into the teaching of the undivided Church.9

Bishop Danilo lists the doctrinal matters at issue:

The Filioque, the absolute primacy of the pope and the infallibility of the pope, the inquisition and indulgences, created grace, purgatory, the abolishment of the epiclesis—the invocation of the Holy Spirit at the Divine Liturgy—and, later, the introduction of new non-Orthodox doctrines concerning the Mother of God, the elimination of fasting, etc.10

Though several issues contributed to the schism, it was really papal claims from Rome in coordination with the unilateral insertion of the phrase “and the Son” (Filioque) by Rome into the Nicene Creed that caused the rupture in unity. History books frequently recount a scene AD 1054 where papal legates bring notice of excommunication to the Patriarch of Constantinople to dramatic effect, but it is not altogether clear that this moment was a clean break. Bishop Danilo writes,

The chasm between Orthodoxy and the Latin West became particularly acute after the coming of the Crusaders to the East in the beginning of the 13th century, and the establishment of a Latin kingdom in Constantinople (1204 AD). The Western occupiers desecrated many shrines in the East, and even trampled upon our Holy Communion in the chalice. The result was a chilling of that mutual, centuries-old brotherly love that held us in unity.11

With the sack of Constantinople, Communion was certainly broken. Conversations resumed at the Council of Florence in the fifteenth century, but to no effect—and only in the modern era have ecumenical conversations between Orthodoxy and the Roman Pope resumed.

Ecumenism

The Orthodox Christian Church sees herself as the fullness of the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Christian Church. Orthodox clergy have at times and places participated in ecumenical conversation, but Orthodox involvement in ecumenical relations and dialogues tends to be one of witness more than dialogue. Orthodox ecumenism is seen as part of the gospel injunction “to preach the gospel to every creature” (Mark 16:15).12

Orthodoxy: A worldwide faith

As Christianity spread throughout the world, the faith left its mark on the societies that received the message. Not only did individuals find Christ, but those individuals made up nations and large groups of people, and Christianity began to permeate entire societies.

This is why today one hears of Orthodox who are called Antiochian, Bulgarian, Greek, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Ukrainian, or the like. “Every culture which embraces the Orthodox Faith makes its own unique contribution to the Church’s manifold expression of her life in Christ.”13

Today, there are fourteen undisputed “autocephalous” (meaning, “self-headed”) Orthodox Churches around the world, and several autonomous Orthodox Churches—along with daughter churches.14 The Antiochian Orthodox Church traces its lineage back to the apostles Peter and Paul, who established the church in Antioch. Greek Orthodoxy, one of the most well-known branches, is deeply rooted in the Byzantine tradition. Russian Orthodoxy emerged as a significant branch of Orthodoxy following the Christianization of the Kievan Rus in the tenth century.15

Each regional church has its own history and “hagiography,”16 as well as unique liturgical, musical, and artistic traditions; they are nonetheless united in faith. “This life of Holy Tradition is dynamic. Its content does not change. This remains eternal. However, its outward expression is open to a variety of ethnic expressions.”17 All Orthodox Churches share the same sacraments, the same divine liturgy, and the same belief in apostolic succession and the Nicene Creed.

In other words, all Orthodox Churches hold the same tradition, the same faith, and the same basic piety, even if there are slight variations in practice.

Faith in Orthodox Christianity is more than mere intellectual assent to a set of beliefs. It is intimately linked to our piety (or spiritual practices), as the Church guides us on a transformative journey towards God, leading to a change in one’s entire being. Orthodox theologians often speak of the doctrine of theosis when speaking of salvation (see below for further explanation). Practices such as prayer, fasting, and partaking in the sacraments are crucial to this transformative journey, as God transforms the person in a kind of synergy. Boosalis writes:

We are not called to simply “follow” Tradition or “mimic” Tradition. We are called to experience it within our own daily lives. We must live Holy Tradition just as the Saints have done and continue to do. Tradition must come to truly exist within us.18

Orthodox faith is tradition

Some may worry about using the word “tradition” to describe Orthodox faith, but it is undeniable that Orthodoxy teaches a set of core beliefs—with a particular way of reading Scripture and of understanding the faith. Orthodox Christians see it as a divine calling to protect the treasure of Orthodox faith, beliefs which are rooted in the Holy Bible and are believed to have been passed down from the Apostles through the centuries; beliefs that continue to guide Orthodox Christians in their faith today.

Tradition is more than mere customs or practices passed down through generations. It is viewed as life of the Holy Spirit within the Church, guiding the Church in truth throughout the ages. Boosalis says that the “Orthodox Church does not exist apart from Holy Tradition,” and that “Holy Tradition is the very source from which the life-giving waters of Orthodox spiritual life and theology flows forth.”19 Tradition includes the written teachings of the church, such as Scripture and the writings of Church Fathers, as well as unwritten elements—such as the Divine Liturgy, holy icons, and the lives of the saints.

These elements of tradition are viewed by the Orthodox not as antiquated or irrelevant, but as a profound source of spiritual wisdom for the faithful.

Holy Tradition is the presence of the Holy Spirit in all generations of Orthodox Christians to the end of the age and the world, no matter the number. It is the fruit of the mystical cooperation of the Holy Spirit with spirit-bearing men. That living and life-bearing Holy Tradition which encompasses both the written word of God and unwritten experience of holy men, is particularly witnessed in the works of the Holy Church Fathers, the Canons of the Church, the decisions of the Ecumenical Councils and of the local Church councils confirmed by them.20

There can be no doubt that Orthodox Christianity is committed to tradition. St. John of Damascus said,

We will not remove the age-old landmarks which our fathers have set, but we keep the tradition we have received. For if we begin to erode the foundations of the Church even a little, in no time at all the whole edifice will fall to the ground.21

Sources of tradition

As mentioned earlier, Orthodox Christianity makes the bold claim to be the original church. What are the Orthodox sources of belief, what constitutes tradition, and what are the authoritative sources for Orthodox doctrines and dogma? Scholar and bishop Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev provides a helpful summary of the sources of tradition, in order of importance:22

1. Holy Scripture

The Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testament are held as an unconditional and indisputable authority. Written by human hands under divine inspiration, the Bible is a reliable guide to the revelation of God among mankind, and the foundational text for Christian faith and practice. Alfeyev notes: “Scripture grew out of tradition and composes an inseparable part of it.”23 It is worth mentioning that the Orthodox Church places a strong emphasis on the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, as the basis for the Old Testament text and canon.24

2. Liturgica tradition

The mature liturgical tradition of the Church is seen as an unconditional and indisputable authority in Orthodoxy.25 These traditions include the celebration of the Eucharist and other sacraments, the use of icons, the cycle of feasts and fasts, and the form and structure of worship. The mature and time-certified liturgical services of the church can therefore be seen as a reliable guide to the content and meaning of the Orthodox faith.

3. Creeds and councils

The creeds and councils of the church, such as the Nicene Creed and the Seven Ecumenical Councils, are given high authority alongside the canonical Scriptures and liturgical texts. “The dogmatic statements of the ecumenical and local councils, which have also undergone the same process of acceptance, also enjoy the same authority, though it must be remembered the council decisions ought not to be examined outside of the context in which they were written.”26

4. Church Fathers

“Next in significance after Scripture, liturgy, and councils are the writings of the church fathers on doctrinal questions.”27 The testimony of the Church Fathers is of high importance to Orthodoxy, providing a deep resource for understanding how the church should interpret the Scriptures and apply them to the lives of believers. Similarly, insights may also be gleaned from other early Christian teachers, who are not considered saints or “fathers” but may nonetheless be used profitably “inasmuch as they correspond” to the teachings of the church.28

5. Apocrypha

Also of note, certain pieces of apocryphal literature of late antiquity that have influenced the church either directly or indirectly, while not part of the canonical Scriptures, should be considered to provide insight into the beliefs and practices of the early church.29

6. Theological teachers and writings

Finally, the Bible calls the church “the pillar and foundation of the truth” (1 Tim 3:15), and so Orthodox teachers and theological writings of more recent times, up to and including modern times, also should be considered valuable, even if in a qualified way. These teachers continue to contribute to the formation of Orthodox Christian faith and life through the generations—provided it stands the test of fidelity to church tradition.

Bishop Danilo and Hieromonk Amfilohije summarize Orthodoxy’s approach to tradition this way:

That living and life-bearing Holy Tradition, which encompasses both the written word of God and unwritten experience of holy men, is particularly witnessed in the works of the Holy Church Fathers, the Canons of the Church, the decisions of the Ecumenical Councils and of the local Church councils confirmed by them.30

So what are the core beliefs of this Orthodox tradition?

At the heart of Orthodox Christianity lies the belief in the Holy Trinity, which is the belief in one God eternally existent in three persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ), and God the Holy Spirit. Orthodox Christians believe that each person of the Trinity is co-eternal, uncreated, fully and equally God. This understanding shapes the Orthodox view of God as a divine community of love and sets the pattern for human relationships and community.

The divinity of Jesus Christ is a central tenet of Orthodox Christianity, and it is crucial to the revelation of God as Trinity. Orthodox Christians affirm that Jesus Christ is true God and true man, two natures united in one Person. He is the incarnate Son of God, born of the Virgin Mary, who suffered, died, was buried, and rose from the dead to conquer sin and death and to grant us eternal life.

The Orthodox understanding of salvation is that Christ destroyed death and made everything possible for the salvation of mankind. From the prayers and hymns of the church:

Let the heavens be glad and let earthly things rejoice; for the Lord has wrought might with his arm. He has trampled down death by death and become the firstborn of the dead. From the belly of Hades has he delivered us and granted the world great mercy.

Having been nailed to the Cross … You have poured forth salvation, O Christ, to all people.31

Theosis

One of the most distinctive teachings of Orthodoxy is that of theosis. Orthodoxy teaches that once death has been conquered, we are called to union with the source of Life. Through the power of the Holy Spirit, we are made “partakers of the Divine Nature” (2 Pet 1:4)—a process we call theosis, or deification, in which individuals are drawn into closer relationship with God and transformed into his likeness. “He was made man so that we might be made god,” as St. Athanasius famously stated (On the Incarnation 54.3). Or, as Frederica Mathewes-Green put it, “As red dye saturates a white cloth by the process of osmosis, so humans can be saturated with God’s presence by the process of theosis.”32 Salvation, in an Orthodox perspective, must include transformation in order to be authentic: “We are being healed of the wounds we bear from our own sins and those of others, and turned into the person God had in mind before we were formed in the womb (Jer. 1:5).”33 We are not God, but God has deigned to save us by taking our condition upon himself. By taking humanity into divinity, theosis has become possible. Some might call this becoming Christ-like; Orthodox Christians call it theosis.

The afterlife

The afterlife, according to Orthodox belief, is a continuation of this journey towards union with God. We hold out the possibility of life eternal with God in the heavenly kingdom—as well as the sobering possibility of eternal condemnation. Nonetheless, prayer and memorials for the dead are important to Orthodox Christians, and we observe regular memorials for loved ones, especially in the early days of their departure. We expect the Second Coming of Christ to usher in the Final Judgment and the eternal state of the cosmos. As the Creed says, “I look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the age to come.”

The sacraments

The sacraments, or Holy Mysteries, are integral to the Orthodox faith and include Baptism, Chrismation, the Eucharist, Confession, Marriage, Ordination, and the Anointing of the Sick. These Mysteries for the Orthodox are viewed as the means through which God’s grace is imparted to believers. It is common to number these liturgical rites at seven, but Orthodoxy is not strict about this. Indeed, St. Theodore the Studite even counts monasticism among the sacraments of the church, so the Orthodox Church has by no means strictly limited their number to seven.34

The Eucharist holds a central and pivotal role in Orthodox life and worship, serving as the chief act within the Divine Liturgy. Bishop Danilo says that the Eucharist is considered “the heart and hub of all the Mysteries of God in the Church,” with “no Christian life without Communion in the Body and Blood of Christ the Lord.”35

Partaking of the Holy Mystery of Communion is a medicine of immortality and eternal life, and serves in part to “continually renew our covenant with Christ our Lord, both individually and as the ‘People of God.’”36 Frederica Mathewes-Green makes Orthodox claims clear: “When we partake of Communion we really do receive the body of Christ. It is, inexplicably, a joining of our awkward and misused, overindulged bodies with the body of its Creator and source of its life.”37

Veneration of icons

The Orthodox Church also places a great emphasis on the veneration of icons, which are images of holy people for use in church or at home. Holy images have played an important role in Christian worship since early centuries, dating at least back to the catacombs, and were an important part of the “Triumph of Orthodoxy” (AD 787) at the Seventh Ecumenical Council. The Holy Fathers are clear that Christians should worship God, not saints or wood and paint—but Orthodox Christians do believe we can honor our beloved elder brothers and sisters who have reached Christ’s kingdom ahead of us in holiness, and we can use the media of wood and paint to do so.38

Monastic tradition

An important part of Orthodox Christianity is our mature monastic tradition as exemplified in the monasteries of Mount Athos, Meteora, Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, and beyond. Mount Athos itself, for example, has been a spiritual lighthouse in the world for nearly 1,200 years, even if it can only be reached by boat. “Monks are men [and women] who disavow the passable things of this world for the sake of Christ and the Kingdom of Heaven, and who struggle to be faithful to Christ until death.”39

Monks do spiritual battle daily as they fast and pray for the salvation of the world, and indeed monasticism highlights

the innate ascetic spirit, the integral liturgical life and the unending pursuit of prayer which compose and characterize the life of the Orthodox Church. … The way of monasticism, traditionally referred to as the “university of the desert,” serves as a school wherein one commences the ultimate education in the science of the hidden ways of the human heart; the font wherein the abundant life of Holy Tradition comes alive in all its fullness.40

There are other ways they impact our churches in the world—our rich tradition of iconography, our fasting practices throughout the year, and even our liturgical music are each imprinted with monastic fingerprints.

One doesn’t have to be a monk to be a saint, but it certainly helps.

Prominent Orthodox figures

We have already seen how important the saints, early Church Fathers, and ascetics are to the story of Orthodoxy—these prominent figures whose teachings and actions have left an indelible impact on the faith, and can be seen as the great navigators of Orthodox Christianity even now. Orthodox Christians believe that, having gone before us as spiritual mariners, as celebrated saints they now serve as the lighthouses guiding the faithful through the vast spiritual ocean of the world with the light of Holy Orthodoxy. Frederica Mathewes-Green writes,

The whole universe is more porous than we think. The saints are always before the throne of God, but in a mystery, they’re also with us. ‘Since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses’ (Heb. 12:1), we are never alone. The ‘great cloud’ accompanies us in our daily lives and supports us in our spiritual combat. They are our unseen companions, our older brothers and sisters in the faith, whose prayers help us wend our way through this fallen world.41

In Orthodoxy, saints continue to accompany us as the Church Triumphant, bolstering the Church Militant with their prayers from God’s throne. To acknowledge their enduring presence, we embellish our parish walls and home prayer corners with icons. These are not mere tokens of their past existence; instead, they serve as a testament to their continuing existence and their vibrant life in Christ.

“Our life is not schizophrenic, a separation of the bodily from the spiritual;” Archimandrite Vasileios explains, “that is why we speak of the sanctification of both the soul and the body.”42 So in addition to knowing that saints are in heaven around the throne, and that they are painted upon the walls of our churches, we often will have relics of saints in our churches, connecting us to the bodies of the holy ones who have been energized by the Holy Spirit.43

Let’s delve briefly into the lives and teachings of a few of these prominent figures: St. Ignatius of Antioch, St. Athanasius the Great, and St. John Maximovitch.

St. Ignatius of Antioch

Known for his devotion to Christ and called the God-bearer, he was the third bishop of Antioch. His letters, written en route to his martyrdom in Rome probably around AD 107, provide invaluable insights into early Christian theology and the church’s structure. His teachings, particularly on the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist and the importance of unity under the bishop’s authority, remain important to Orthodox faith and practice today. St. Ignatius is also credited with introducing the term “Catholic Church,” which for us carries a sense of wholeness, fullness, and universality of Christ’s church and the power of the gospel. Widely regarded as a friend and disciple of the apostle John, it is remarkable to many observers how Orthodox his theology truly is.

St. Athanasius the Great

A bishop of Alexandria in the fourth century who dedicated his life to defending the Orthodox teachings about the divinity of Christ against the Arian heresy. His seminal work, On the Incarnation, offers a profound understanding of the Incarnation’s significance, and remains the gold standard on the subject. As the Patriarch of Alexandria in a time of great unrest and controversy, St. Athanasius faced exile and persecution for his unwavering commitment to upholding the true faith, earning him the title “Father of Orthodoxy.” Despite these hardships, he tirelessly fought for the unity and orthodoxy of the church, and through his steadfastness and perseverance, left a lasting impact on Christianity forever. His life serves as an inspiring example of standing firm in the face of adversity and defending the truth despite personal consequences.

St. John Maximovitch

Fast forward to the twentieth century, and we find St. John Maximovitch, a Russian Orthodox bishop who served the faithful in various capacities in Europe and America. He was known for his humility, asceticism, prayerful life, as well as care for orphans, the poor, and the sick. St. John was especially instrumental in preserving Orthodoxy amongst the Russians scattered abroad in “diaspora.” His life was a testament to the Orthodox faith’s enduring power, even in the face of modern challenges.

These spiritual mariners and many others have guided Orthodoxy through the centuries, each contributing to the faith’s rich depth and texture. Their teachings continue to inspire and guide Orthodox believers on their spiritual journey, and we believe their prayers strengthen the church on her journey to the kingdom even now.

Deeper aspects of Orthodoxy

The Orthodox church carries treasures of profound spiritual depth. These treasures, known as sacraments, prayer and fasting regulations, and the liturgical calendar, help guide the Orthodox believer, providing a deeper connection with God.

Holy Mysteries

Earlier, we mentioned the seven sacraments or holy mysteries that are integral to the belief and practice of Orthodox Christianity.

- Baptism, the first sacrament, is a spiritual regeneration and initiation into the Christian community.

- The newly baptized is then sealed with the gift of the Holy Spirit during Chrismation, marking full membership in the church.

- The Eucharist, or Holy Communion, is the most frequently observed sacrament, where believers partake of the body and blood of Christ, engaging in a continual relationship with him and being transformed by his real and life-giving presence.

- Confession is for all Orthodox Christians, and provides a means of repentance, offering forgiveness of sins, and time for counsel.

- The Anointing of the Sick provides healing and comfort to the physically and spiritually afflicted, and is offered in some parishes as a formal service during Lent (or at other times of the year).

- The sacrament of marriage unites a man and woman in a holy union, symbolizing Christ’s love for the church.

- Ordination sets apart individuals for the clerical roles within the church. For our clergy, if they are to be married they must be married prior to ordination.

Prayer and fasting

Notably, prayer and fasting hold a central place in the Orthodox spiritual journey. The church encourages daily prayer, with specific prayer rules. Many clergy, monks, and laypeople alike embrace practices such as the Jesus Prayer using a simple knotted prayer rope. Fasting, traditionally observed on Wednesdays and Fridays (and during specific seasons such as Great Lent), is seen as a spiritual discipline, fostering humility and self-control—we are called to fast about half the year, and we are taught to do so corporately rather than individually (much like we see the people of God do in Isaiah 58).

Bishop Danilo explains how fundamental fasting is to us as people:

The first of God’s commandments in Paradise was about fasting, i.e. self-restraint. Therefore man’s first sin was against the fast. Just as both soul and body participate in sin, so both must participate in virtue and liberation from sin. The goal of fasting is the purification of the body, strengthening of the will, and elevation of the soul. By fasting, Christians unceasingly recall Christ’s suffering for their salvation. The true fast has two sides: physical and spiritual. … Fasting serves to multiply love and prayer, and the readiness to carry out all the virtues of the Gospel. The soul has two wings with which it flies to heaven: fasting and prayer. These are a medicine for spiritual and bodily illnesses, and from every demonic action. The Savior Himself said: ‘This kind does not go out except by prayer and fasting.’ With fasting, the soul and body are prepared to become a temple of the Holy Spirit. True spiritual life is unimaginable without fasting.”44

Liturgical life

The liturgical life of the Orthodox Church is rich and beautiful, and contains a wealth of material to explore. It includes the Divine Liturgy, the Hours, Vespers, and Orthros (or Matins):

- The Divine Liturgy, the primary worship service, is a celebration of the Eucharist.

- The Hours are short services marking the divisions of the day.

- Vespers and Vigils, conducted in the evening, are services of thanksgiving for the completed day and the ushering in of the new one.

- Orthros, or Matins, is the morning service, usually preceding the Divine Liturgy.

It does not take long to notice in Orthodoxy that there are often services that precede the service, so it can be confusing for visitors who arrive on time for liturgy that a service is already in progress.45

Festivals and feasts of Orthodoxy

As part of their liturgical tradition, the Orthodox have a calendar. The Orthodox church year begins on September 1. We have many holidays on our calendar, which includes both fixed and movable feasts. The fixed feasts, like Nativity (Christmas) and Theophany (Epiphany), occur on the same calendar date each year, while movable feasts, like Pascha (Easter), vary each year. The fasting seasons, including Great Lent and the Nativity Fast, prepare believers for the major feasts, encouraging self-examination and spiritual growth.

The Orthodox Church’s liturgical year is intended to be a vibrant, living testament to the lives of Christ and the saints. It encompasses a variety of celebrations and feasts, many of which may seem familiar to non-Orthodox Christians, though they often fall on different dates due to the Orthodox Church’s use of two versions of the Julian calendar—as opposed to the Gregorian calendar used by most Western churches.46 Here are some highlights:

Pascha (Easter)

This is the most significant feast in the Orthodox Church, referred to as the “Feast of Feasts.” Pascha, which is the Greek term for Passover, commemorates the resurrection of Jesus Christ and is usually observed a week or two after Western Easter.47 This discrepancy in dates arises from differing methods of calculation. The Orthodox Church follows the original method set by the First Ecumenical Council, held in Nicaea (AD 325). Citing a hymn from the Paschal Canon, the Apolytikion of the Resurrection, Hieromonk Gregorios writes:

Christ’s Resurrection is an event which we actually live and experience, and it is for this reason we are exhorted by the Church to worship the Risen Christ: “Having beheld the resurrection of Christ, let us worship the Holy Lord Jesus.”48

Nativity (Christmas)

Christmas is preceded by a forty-day Nativity Fast, a spiritual preparation period mirroring the Lenten season, and culminates in the celebration of the birth of Jesus Christ. Some Orthodox observe this feast on January 7 (which is currently December 25 in the Julian).

Theophany (Epiphany)

Celebrated in January, Theophany commemorates the baptism of Jesus Christ in the Jordan River and the divine revelation of the Holy Trinity. It is a day of blessing waters in remembrance of this event.49

Ascension

Forty days after Pascha, the Feast of the Ascension commemorates Christ’s ascension into heaven as described in the book of Acts. The Ascension is a significant event, marking the completion of Jesus’s earthly mission and the beginning of the mission of the church.

Pentecost

Celebrated fifty days after Pascha, Pentecost commemorates the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles and other followers of Jesus Christ, as described in the book of Acts. This event sparked the church’s mission in the world and is often referred to as the “Feast of the Holy Trinity.”

Dormition of Mary (Assumption)

This day celebrates the Virgin Mary’s falling asleep and bodily transition from earthly life to eternal life. Observed on August 15, it’s preceded by a two-week fasting period.

Great Feasts

These feasts are considered Great Feasts, pivotal events in the life of Christ or the Theotokos (Greek, “God-bearer” or “Mother of God”), and are observed with special liturgies and vigils. There are twelve Great Feasts in total, including those mentioned above. The festivals and feasts of Orthodox Christianity are not just dates on a calendar. They are meant to be a spiritual journey through the lives of Jesus Christ, of the Theotokos, and of the saints. They encourage the faithful to participate in the mystery of faith in a profound, tangible, and communal way. Each celebration is a reminder of God’s love and the promise of salvation, bringing the spiritual ocean of Orthodoxy to life through worship, prayer, fasting, and communal fellowship.

Lesser Feasts

In addition to these feasts, there are Lesser Feasts celebrating various saints and events in church history. Boosalis observes:

By sharing in this same ecclesial life of the Orthodox church, following the same liturgical cycles, singing the same hymns, reciting the same prayers and following the same ways of Prayer, being inspired by the same Scriptural readings, observing the same fasts and celebrating the same feasts—all Orthodox believers from throughout the centuries of the church’s existence, share a common Faith and communal experience of the abundant life in Christ.50

How the Orthodox approach Bible study

The Orthodox Church has a rich and deep approach to Bible study. We believe it to be an approach steeped in centuries of tradition, shaped by deep theological insights, and focused on personal spiritual growth.

But on closer examination, it is simply New Testament Christianity. “The New Testament and the church can never be separated or isolated from one another. They are interdependent and mutually inclusive,” writes Boosalis, because the church gave birth to the New Testament and preceded it by decades.51 It’s no exaggeration to say that “the New Testament organically sprang up from within the very life of the Church, and more specifically, from within her liturgical and sacramental life.”52

A guide to the Orthodox church’s approach to Bible study

Orthodox Christianity reveres the Bible as more than just a book; it is the living Word of God to be experienced within the church’s liturgical and sacramental life, a life punctuated by cycles of feasts and fasts, penitence and celebration. Unlike traditions emphasizing private interpretation, Orthodox Christianity encourages a communal reading of the Scriptures, one framed by the church’s tradition. This includes writings of the Church Fathers, Ecumenical Councils’ decisions, liturgical texts, saints’ lives, and church iconography. The Church Fathers, being early Christian writers and theologians, aren’t merely historical artifacts but living guides in the interpretation of the Scriptures today.

Studying the Bible in the Orthodox tradition is meant to be not merely an intellectual exercise but a spiritual journey. These are the kinds of practices Orthodox Christians use for their Bible study:

- Praying before and after reading: Orthodox Christians often begin and end their Bible study with prayer, seeking the guidance of the Holy Spirit in understanding the Scriptures.

- Using biblical commentaries from the Church Fathers: This can provide valuable insights and help prevent misunderstandings—and resources such as the Orthodox Study Bible can be a great start on this path.

- Reading the Bible in the context of the liturgical life of the church: The church’s liturgical texts often quote or allude to the Scriptures. Reading the Bible within this liturgical context can deepen your understanding of the Scriptures.

- Participating in a Bible study group: Many Orthodox Christians join a Bible study group in their local Orthodox parish, providing community, support, and guidance for Bible students.

- Seeking guidance from a priest or spiritual father: St. Paul tells the Corinthians that he was their spiritual father through the gospel (1 Cor 4:15); likewise, Orthodoxy is a spiritual family with “countless Christian guardians.” If Orthodox believers have difficult questions or struggle with certain passages, we often seek guidance from reliable Orthodox clergy.

- Practicing personal devotion: Beyond structured study, the Bible should be part of the daily life of any believer. A regular habit of reading, reflection, prayer, and even fasting is considered beneficial by the Orthodox. Regular reading, reflection, and prayer can help the Scriptures to become a wellspring of spiritual nourishment and growth.

- “Remember God, say your prayers, go to church”:53 Orthodox believers see no better place to learn the Scriptures than in the context of liturgical life. St. Paul says “faith comes by hearing and hearing by the word of God” (Rom 10:17), so we attend liturgy ready to listen with the ears of faith.

Orthodox Bible study is a journey of exploration, discovery, and transformation, inviting believers to encounter the living Word of God within the living tradition of the church, guided by the wisdom of the Church Fathers, and nourished by personal devotion and the liturgical life of the church.

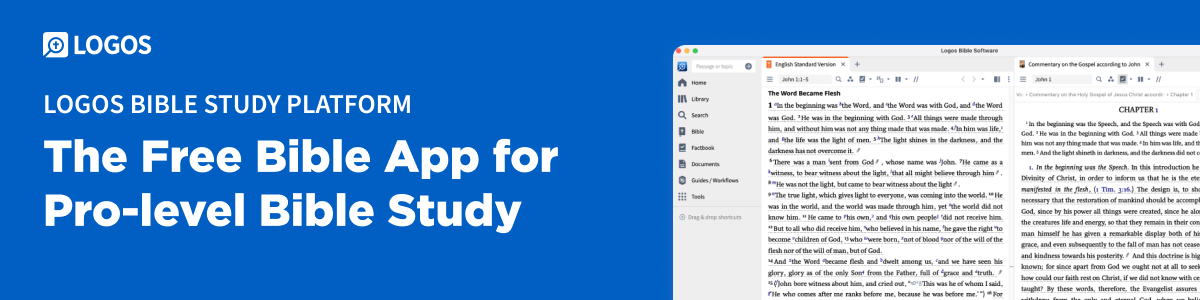

Embracing technology in Bible study

The Logos Bible study platform revolutionizes the practice of Bible study in the digital age. With its extensive digital library, including books, commentaries, and articles, Logos enhances the understanding of Scripture. It offers insights into different Christian traditions, broadening the Bible reader’s theological horizons. But Logos also has a growing collection of Orthodox Christian resources that put the wisdom of the Church Fathers at one’s fingertips.

- The software allows cross-referencing, linking Old Testament prophecies to their New Testament fulfillments, fostering a deeper grasp of the unity of Scripture. This feature is invaluable in grasping the unity of Scripture—a fundamental principle of Orthodox Christianity.

- One of the standout features of Logos is its access to the works of the Church Fathers—the early Christian theologians whose teachings have shaped Orthodox beliefs and practices. Studying these ancient writings is crucial for Orthodox Christians, as they offer invaluable insights into how the early church understood and applied the teachings of Scripture.

- For Orthodox explorers, the Orthodox Bronze library is highly recommended, featuring resources tailored to the Orthodox tradition, including the Popular Patristics Series, the Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture series, and the Works of St. Athanasius series. Logos also offers other libraries, such as the Orthodox Starter library and the Orthodox Silver library, catering to different needs and budgets. Each of these libraries includes a broad selection of Orthodox resources, ensuring that you can find a library that suits your specific needs.

The Logos Bible study platform offers a wealth of resources that can significantly enhance one’s understanding of Scripture. Whether you’re a seasoned scholar or a novice explorer, Logos can assist you in your spiritual journey.

For further reading

Note: The books listed below are recommended by Jamey Bennett, author of this article. Some are available on the Logos platform, but where we have the author’s works but not that particular books on Logos, we’ve linked to the author’s page so you can still access relevant Orthodox works in your Logos library.

Alfeyev, Metropolitan Hilarion. Christ the Conqueror of Hell: The Descent into Hades from an Orthodox Perspective. Crestwood, St. Vladimir’s Seminary, 2009.

Boosalis, Harry. Holy Tradition: Ecclesial Experience of Life in Christ. South Canaan: St. Tikhon’s Monastery Press, 2013.

Gregorios, Hieromonachos, author; Chara Dimakopoulou, trans. The Orthodox Faith, Worship, and Life: Orthodox Catechism: An Outline. Columbia: Newrome Press, 2020 [2012].

Krstic, Bishop Danilo S., and Hieromonk Amfilohije Radovic. No Faith Is More Beautiful than the Christian Faith. Los Angeles: Sebastian Press, 2015 [1982].

Mathewes-Green, Frederica. Welcome to the Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Eastern Christianity. Brewster: Paraclete Press, 2015.

Meyendorff, John. Byzantine Theology: Historical Trends and Doctrinal Themes. New York: Fordham University Press, 1974, 1979.

Archimandrite Vasileios of Iveron, Bishop Maxim Vasijlevic, ed. Thunderbolt of Everliving Thought: ‘American’ Conversations with an Athonite Elder. Alhambra: Sebastian Press, 2014.

- Bishop Danilo Krstic and Hieromonk Amfilohije Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful Than the Christian Faith (Los Angeles, CA: Sebastian Press, 2015), 77.

- Archimandrite Vasileios of Iveron and Bishop Maxim Vasijlevic, eds., Thunderbolt of Everliving Thought: “American” Conversations with an Athonite Elder (Alhambra: Sebastian Press, 2014), 21.

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 51.

- Harry Boosalis, Holy Tradition: Ecclesial Experience of Life in Christ (South Canaan: St. Tikhon’s Monastery Press, 2013), 34.

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 83.

- One might think of the council in Acts 15 as a “prequel” to the Ecumenical Councils.

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 51: “The decisions of some of the Local Councils, both earlier and more recent, have ecumenical significance, because the entire Orthodox Church has adopted them as their own.”

- The Creed from Nicea was expanded at Constantinople, and decreed to be the final draft, subject to no further revision.

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 61–62.

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 61–62.

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 62.

- For more on the complexities of Orthodoxy and ecumenism, see: “On the Attitude of the Orthodox Church Towards the Heterodox and Towards Inter-Confessional Organizations” and “The Orthodox Church and the Ecumenical Movement.”

- Boosalis, Holy Tradition, 15.

- The Orthodox wiki has a list.

- Outside the boundaries of Eastern Orthodoxy is what is sometimes called “Oriental Orthodoxy,” which includes the Armenian, Ethiopian, Coptic, and Indian/Malankara Orthodox Churches, among others. While they share many similarities with Eastern Orthodoxy, their liturgical practices and traditions have developed independently, and their communion is distinct from the Eastern Orthodox Churches. The divergence stems from theological differences that arose in the fifth century, particularly concerning the nature of Christ, and the divide began in earnest with the Council of Chalcedon. Remarkably, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Christians have discovered that they share similar approaches to tradition, liturgy, fasting, and more. Dialogue between Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox theologians have given some hope for reunion, while others have no such confidence. In many areas of the world that face persecution, these two communities are often found to have even closer ties.

- Hagiography refers to the biography or written account of saints or venerated religious figures. It is often used to describe literature that recounts their lives, deeds, and miracles.

- Boosalis, Holy Tradition, 81.

- Boosalis, Holy Tradition, 31.

- Boosalis, Holy Tradition, 18.

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 54–55.

- Cited in Boosalis, Holy Tradition, 35.

- Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell: The Descent into Hades from an Orthodox Perspective (Crestwood, St. Vladimir’s Seminary, 2009), 205-208. This is a helpful appendix that illustrates an Orthodox theological method.

- Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell, 205.

- The Orthodox Old Testament includes Tobit, Judith, Wisdom of Solomon, Sirach (Ecclesiasticus), Baruch, 1 and 2 Maccabees (some Orthodox Bibles include 3 Maccabees), Greek additions to the books of Esther and Daniel (including the Prayer of Azariah, the Song of the Three Holy Children, Susanna, and Bel and the Dragon). These texts from the era of Second Temple Judaism provide a contextual understanding for the New Testament that is missing from Bibles containing only sixty-six books.

- Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell, 206: “Certain works of church fathers can contain disputable or even incorrect opinions. This cannot be said about the canonical liturgical texts, for church tradition throughout many centuries weeds out any such opinions. Therefore, if we were to create a certain hierarchy of authorities, the liturgical texts would come in second place after Scripture.”

- Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell, 206.

- Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell, 207.

- Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell, 207.

- This category of apocrypha is distinct from the books of our Old Testament, which enjoy a much higher authority in the church. An example of later apocrypha is the Protoevangelion of James, which offers us much insight into the theological reflections of the early church, especially surrounding Old Testament types and shadows being fulfilled in Mary and the Incarnation of Christ. The Gospel of Thomas, on the other hand, while considered apocrypha, is thoroughly rejected by Orthodoxy due to its heretical content. Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell, 208: “Apocrypha rejected by the church do not have any standing for the Orthodox believer.”

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 55.

- Cited in Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell, 168–69, 176.

- Frederica Mathewes-Green, Welcome to the Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Eastern Christianity (Brewster: Paraclete Press, 2015), 68.

- Mathewes-Green, Welcome to the Orthodox Church, 144.

- John Meyendorff, Byzantine Theology: Historical Trends and Doctrinal Themes (New York: Fordham University Press, 1974, 1979), 56.

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 40.

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 40.

- Mathewes-Green, Welcome to the Orthodox Church, 70.

- The example may be given of someone kissing a photograph of a beloved relative who lives far away—the photograph is not confused with the relative, but is a symbol of them and provides a kind of connection.

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 64.

- Boosalis, Holy Tradition, 40.

- Mathewes-Green, Welcome to the Orthodox Church, 37.

- Archimandrite Vasileios of Iveron and Bishop Maxim Vasijlevic, eds., Thunderbolt of Everliving Thought: “American” Conversations with an Athonite Elder (Alhambra: Sebastian Press, 2014), 13.

- See this page for more on relics.

- Krstic and Radovic, No Faith Is More Beautiful, 88.

- For this and other surprising firsts for visitors to Orthodox services, see Frederica Mathewes-Green’s “12 Things I Wish I’d Known.”

- The Julian Calendar, despite being thirteen days behind the Gregorian Calendar currently, continues to be used in the Orthodox Church for its liturgical life, maintaining a continuity of worship that stretches back to the earliest days of the Church. This, among many other aspects, is a testament to the Orthodox Church’s commitment to preserving the richness and depth of early Christian traditions. The Julian calendar, introduced by Julius Caesar, was replaced by the Gregorian calendar in the West in 1582 due to a slight error in calculating the year’s length. The Eastern Orthodox Church, however, didn’t fully adopt this change. Some Orthodox churches use the Revised Julian calendar, which largely matches the Gregorian until 2800, while others, like the Russian and Serbian Orthodox, stick to the old Julian calendar. This explains why Orthodox churches sometimes celebrate feasts on different dates than Western churches.

- The celebrations do align every few years, and then every few years they are more than a month apart.

- Hieromonk Gregorios, The Orthodox Faith, Worship, and Life: Orthodox Catechism: An Outline, trans. Chara Dimakopoulou (Columbia: Newrome Press, 2020 [2012]), 62.

- In Western liturgical churches, this holiday recalls the visit of the Magi to worship the infant Christ, which is also a revealing of God, albeit in a different event.

- Boosalis, Holy Tradition, 14.

- Boosalis, Holy Tradition, 63.

- Boosalis, Holy Tradition, 60.

- Fr. Thomas Hopko was given this instruction by his mother as he went off to seminary.