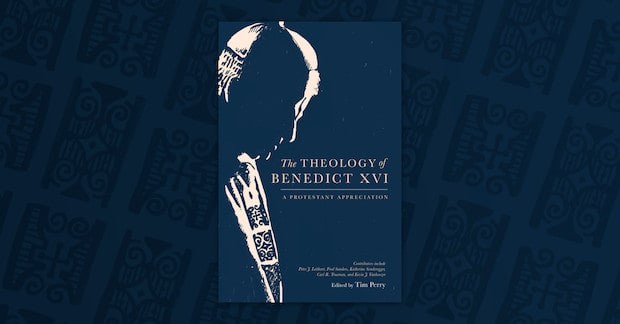

Why read a book of Protestant appreciation for Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI/Joseph Ratzinger?

First, it helps clarify some misunderstood doctrines of the Catholic Church.

Second, the prevalence of Catholicism should challenge Protestant pastors, ministers, and theologically-minded laypeople to understand what our Catholic friends, neighbors, and classmates believe.

Joey Royal, author of an essay about the Eucharist in Lexham Press’ new book on Benedict XVI, adds another answer to the question:

To better understand Catholic thought through one of its most important and articulate exponents, to see an Augustinian theology that overlaps with Protestantism in key ways but deviates from it in other key ways, to see how Ratzinger’s theology is saturated in Scripture, and to deepen one’s own understanding of Scripture by reading him. To clear away misunderstandings around key themes of Christian thought and hopefully lead to better dialogue and more unity among Christians in the West.1

We can glean this kind of understanding in The Theology of Benedict XVI: A Protestant Appreciation. Contributors Fred Sanders, Gregg Allison, and Carl Trueman, among others, guide readers toward a Protestant understanding of common ground—and key differences—with the theology of Joseph Ratzinger/Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI.

The following excerpt comes from a chapter by Kevin J. Vanhoozer on revelation, tradition, and biblical interpretation that demonstrates the careful engagement with Benedict’s work in The Theology of Benedict XVI.

***

In a presentation celebrating the one-hundredth anniversary of the Pontifical Biblical Commission, Cardinal Ratzinger refers to Moses gazing on the promised land “of an exegesis liberated from every shackle of magisterial surveillance.”2 Whereas exegetes in the first half of the twentieth century were barred from entry, Vatican II marks “the entrance into the Promise Land of exegetical freedom.”3

However, freedom with no boundaries risks destroying itself. The magisterium no longer imposes norms on exegetes, yet the text does, and tradition is faith’s reception of divine revelation in and through the text of Scripture. There is no such thing as pure exegetical objectivity, and when biblical scholars pretend there is, they lose sight of the Bible’s special and specific (theological) nature.

For Ratzinger, we might say, faith has its reasons that a purely critical reason cannot know. Faith receives the Christ presented in the Scriptures, but the Christ of the Scriptures is also the Jesus of history. Yet the full truth of the Jesus of history, the revelation of the Father, must be received in faith. Faith is a mode of knowing, and the critical attempt to set faith aside “does not produce pure objectivity, but sets up a cognitive standpoint that rules out a certain [theological] perspective.”4

Here it is important to recall Ratzinger’s insistence that the church, the community of faith, is the “living presence” of the word, and that the church’s bishops are the concrete corporate form of tradition. To read in faith means, for Ratzinger, to read as a member of the church, a single reading subject.5

Apart from the concrete reality of the church (that is, lived Roman tradition), Scripture becomes a victim of experts’ disputes.

Differences between evangelicals and Roman Catholics of course remain. The most important concerns the pattern of interpretive authority and the catholicity of the church. For Benedict, Scripture, tradition, and the Roman magisterium always coincide, because they are guided by the same Spirit. By way of contrast, evangelicals acknowledge that, tragically, the church sometimes errs, both by misinterpreting what is said or by adding to what is not. Scripture therefore retains supreme authority over Roman tradition and interpretations. The Bible, not the college of bishops, is our ultimate authority. Moreover, evangelicals acknowledge the positive role of catholic tradition in biblical interpretation, but point out that Rome does not enjoy a monopoly on catholicity.6

Ratzinger’s most enduring legacy may well be his attempt to make good on Vatican II’s claim that “the study of the sacred page should be … the very soul of theology.”7

At the same time, he also insists that exegetes “do not stand in some neutral area, above or outside the history of the Church … [rather] the faith of the Church is a form of sympathia without which the Bible remains a closed book.”8

Indeed, Roman Catholic scholars, thanks to Ratzinger’s leadership, may now be ahead of evangelicals as far as being intentional about not putting asunder what God has put together: exegesis and theology.9

As one Catholic biblical scholar puts it, “Today it is starting to be an established fact for Catholic exegetes that the interpretive task must not stop with the historical-critical dimension but must go as far as theology.”10

In Benedict’s words, “Where theology is not essentially the interpretation of the Church’s Scripture, such a theology no longer has a foundation.”11

As an evangelical, I not only appreciate Ratzinger’s exhortation to do theology biblically and to read the Bible theologically; I also say, “Amen.”

***

This post is adapted from The Theology of Benedict XVI: A Protestant Appreciation, available now through Lexham Press.

The headings and title of this post are the additions of the editor. The author’s views do not necessarily represent those of Faithlife.

- https://blog.lexhampress.com/2019/11/04/appreciating-the-theology-of-benedict-xvi-a-round-table-interview/

- Joseph Ratzinger, “Exegesis and the Magisterium of the Church,” in Opening Up the Scriptures: Joseph Ratzinger and the Foundations of Biblical Interpretation, ed. José Granados, Carlos Granados, and Luis Sánchez-Navarro (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), 128.

- Ratzinger, “Exegesis and the Magisterium of the Church,” 129.

- Ratzinger, “Exegesis and the Magisterium of the Church,” 135.

-

Ratzinger appeals to Gal 2:20 (“It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me”) in support of the claim that the church is not an abstract principle but a single and living (reading) subject (Nature and Mission, 51–52, 61).

-

For an expansion of this point, see my “A Mere Protestant Response,” in Matthew Levering and Kevin Vanhoozer’s Was the Reformation a Mistake? Why Catholic Doctrine Is Not Unbiblical (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2017), 191–231.

- Dei Verbum, §24.

- Ratzinger, “Biblical Interpretation in Crisis,” 22–23.

-

See the essays in Carl, Verbum Domini and the Complementarity of Exegesis and Theology—particularly Pablo Gadenz, “Overcoming the Hiatus between Exegesis and Theology: Guidance and Examples from Pope Benedict XVI,” 41–62.

-

Carbajosa, Faith, The Fount of Exegesis, 249. However, Carbajosa does not see theology as a second step beyond exegesis, as if the text were not inspired by God, but rather as a second dimension, alongside the historical, in what ought to be a single exegesis.

- Benedict XVI, Verbum Domini, 56.