It is now a general consensus among New Testament scholars that, despite its deviations from Jewish traditions, early Christianity can nevertheless be understood as a Jewish phenomenon. Even so, we all recognize that the “Jewish world” of the first century was not just the “Jewish world”: a plethora of theological ideas and religious practices regularly circulated throughout the ancient Mediterranean and exerted constant influence across a variety of religious groups.

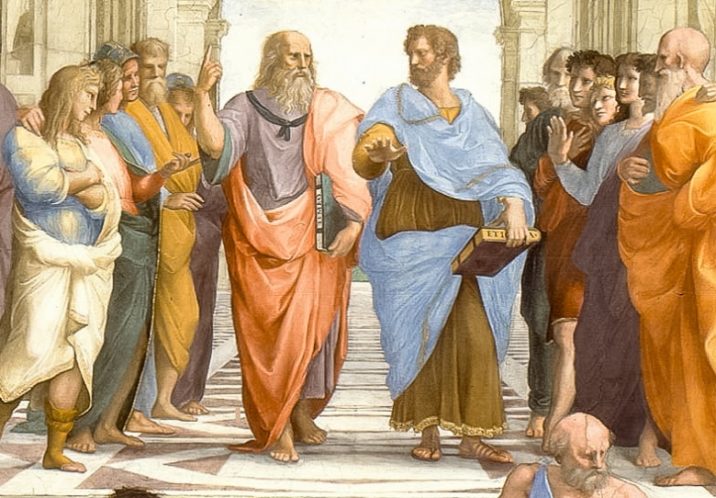

That being the case, we must always remember that many early Christians configured their ideas in dialogue, and in tandem with, Graeco-Roman philosophical traditions—and, of course, numerous scholars have long noticed early Christianity drawing from and engaging with their philosophical contemporaries.

This post is an invitation to a specific kind of thought experiment stimulated by the proximity between the earliest Christians and their philosophical neighbors. What if, just for a moment, we set aside questions of origin or influence and read the New Testament from the various perspectives of the Graeco-Roman philosophical traditions? What if we imagined ourselves in their shoes and painted a picture of how they might react to reading early Christian documents?

I want to engage in such an experiment by scrutinizing some aspects of Paul’s letters with Aristotelian eyes. To make this more specific, I will utilize Aristotle’s configurations of ἐνέργεια and friendship as the position from which we can reread some of Paul statements about salvation and agency. While this will permit Aristotle, in a sense, to dictate the rules of engagement and the categories of analysis, this approach might just make Paul come alive in a new light and bring fresh insights about his theology to the surface.

Aristotle: Ἐνέργεια Extended

Across multiple works, Aristotle sets forth what can be called an “actualistic ontology”—that is, he doesn’t make a sharp distinction between being and acting. Well, actually, he doesn’t make a distinction between these at all; for Aristotle, action is coextensive with and identical to being. At the same time, Aristotle also insists that our action or energy (ἐνέργεια) can extend beyond ourselves in cases where we create or influence things. Put differently, when we act upon things, the energy those things receive from us is still, in fact, our energy, only contained in something else. Yet if our ἐνέργεια can be contained in the things that we make and influence, and if ἐνέργεια and action are identical to being, this means that the things we make or influence actually contain our very being. If all of this seems rather convoluted, here are some of Aristotle’s own articulations:

Actuality (ἐνέργεια) resides in the thing produced (τὸ ἔργον); e.g. the act of building in the thing built, the act of weaving in the thing woven, and so on; and in general the motion resides in the thing moved … Evidently, therefore, substance (οὐσία) or form (εἶδος) is activity (ἐνέργεια). (Met. IX, 1050a30-1050b3)

We exist by virtue of actuality (ἐσμὲν δ᾽ ἐνεργείᾳ) (that is, by living and acting [τῷ ζῆν γὰρ καὶ πράττειν]); and one’s product is, as it were, the maker-in-actuality (ἐνεργείᾳ δὲ ὁ ποιήσας τὸ ἔργον ἔστι πως). (NE 1168a6-10)

The last claim—that the maker is what she produces—is the natural conclusion of the double contention that our being is our ἐνέργεια and our ἐνέργεια is contained in what we make or influence.

For Aristotle, however, this configuration applies not only to one’s relationship to objects but also one’s relationship to people. For example, he argues that when a teacher acts upon a pupil by transferring her knowledge to the pupil, the energy or activity of the teacher becomes contained in and expressed by the pupil:

It is not absurd that the actualization (ἐνέργεια) of one thing should be in another. Teaching is the activity of a person who can teach, yet the operation is performed in something—it is not cut adrift from a subject, but is of one thing in another. (Phys. 202b5-6)

Aristotle suggests that the ἐνέργεια of one person can be located in another person in cases where the former influences and acts upon the latter. This might seem rather strange, because modern notions of individual autonomy will naturally lead us to think that we are utterly self-determining agents, and if someone’s ἐνέργεια determines my actions, then I am unable to have any ‘real’ ἐνέργεια of my own. Aristotle, by contrast, does not insinuate that acting upon and extending ἐνέργεια through others limits or snuffs out their own capacities for self-determination. While your ἐνέργεια might be present in me, I do not lose any of my own ability to express ἐνέργεια. Our ἐνέργεια can, as it were, coexist.

But given Aristotle’s actualistic ontology, shouldn’t he conclude that when someone extends their ἐνέργεια to another, the actor also extends her own being to this other? This precise configuration comes to clear expression in Aristotle’s concept of friendship. First, note how Aristotle suggests that virtuous friends make each other more virtuous through exerting their virtuous ἐνέργεια upon one another:

But the friendship of good people is good, and increases through their association (ὁμιλία). They seem to become even better (βελτιόω) through their activity (ἐνεργέω) and their improving (διορθόω) each other, because each takes impressions (ἀπομάσσω) from the other of what meets with his approval, which gives rise to the saying, ‘From noble people comes nobility’ (NE IX.12, 1172a11-14).

For Aristotle, virtuous friends take on each other’s properties, sharpening each other through their continual mutual association; put another way, they symmetrically shape one another as they extend their properties to and exert ἐνέργεια upon one another, such that each friend’s virtuous behavior becomes an expression of the other’s ἐνέργεια. This process is continuous: I exert influence over my friend, who then becomes more virtuous and then exerts influence upon me, which makes me more virtuous, and on it goes. This process results in ἐνέργεια between friends becoming directed toward the same virtuous end.

In light of Aristotle’s claim above that another way of talking about “activity” (ἐνεργεια) is “living” (ζάω), it is no surprise that he states that for friends the most desirable thing is “co-living” (συζάω), which is seen in how they drink together, do sports together, and study together (NE IX.12, 1172a5-7). More importantly, the fact that he considers friends to exert ἐνέργεια upon one another implies that each friend contains the other friend’s ἐνέργεια; and, again, this would furthermore mean that friends share the same being. Aristotle says precisely this when he claims that, as friends mutually shape one another and extend their ἐνέργεια upon and through each other, each friend becomes another self (ἔστι … ὁ φίλος ἄλλος αὐτός) (NE XIII 12, 1161b). As they are mutually transformed by each other, friends share their being with one other.

Let me isolate some conclusions before moving on to Paul. First, Aristotle considers the things which we act upon to contain and express our ἐνέργεια through their ἐνέργεια. Second, when one’s ἐνέργεια is contained within another thing or person, it does not compete with or detract from another’s own ἐνέργεια. Third, when friends extend their ἐνέργεια through each other, it leads to a kind of shared being between them.

Paul: Christ Lives in Me

So what does this have to do with Paul? Well, let’s try to imagine reading some of Paul’s statements about Christ from the Aristotelian perspective outlined above. In various places, Paul suggests that Christ takes on human properties: Christ was sent “In the likeness of sinful flesh” (Rom 8.3), “became under law” (Gal 4.4), “became a curse” (Gal 3.13), and became “born in the likeness of man” to the point of becoming “obedient unto death” (Phil 2.6–8). In Aristotle’s words, various properties that belonged to humanity are transferred to Christ. What is initially curious about this is that Christ doesn’t take on human properties by being influenced by human ἐνέργεια; he voluntarily takes on these properties of his own accord (Phil 2.6) or by the direction of the Father (Gal 4.4; Rom 8.3). Yet, perhaps counterintuitively, by taking on these human properties, Christ transfers his own properties and virtues to others. Now we are back in some familiar Aristotelian territory. By “redeeming” believers (Gal 3.13, 4.5)—that is, by acting upon them—Christ transfers his positive properties to believers: they receive his blessing (Gal 3.13–14), his status as Son, and his Spirit (Gal 4.5–6).

Furthermore, Aristotle would be pleased to find that this transfer of properties does not remain static. Since Christ has acted upon them and transferred his properties to them, all of this comes to expression in their own action. It is through the Spirit of Christ they received as a result of the Christ-event that enables them to act virtuously like Christ, since the Spirit is the means by which they are empowered to “love” (Gal 5.16), the same virtuous activity performed by Christ himself (Gal 2.20).

While both parties take on the properties of one another, the mechanism by which this happens is not, as in Aristotle’s configuration of friendship, symmetrical. It is asymmetrical: whereas humans take on the properties and virtues of Christ by his action (ἐνέργεια), Christ does not take on their properties by their ἐνέργεια—he does that of his own accord. If Aristotle followed Paul up to this point, how would he configure the relationship of ἐνέργεια between Christ and believers? He would not be able to say that human beings extend their ἐνέργεια through Christ. However, since Christ has transferred his properties to them, and because this causes them to act as Christ acted—in (virtuous) love—Aristotle would have to say here that the ἐνέργεια of Christ is contained within and expressed by the ἐνέργεια of believers.

In Aristotle’s eyes, then, Paul’s announcement that “it is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God” reads quite coherently with an Aristotelian ontology. Well, of course Christ lives in me: Christ acted upon Paul and led him to act virtuously, and this means that Christ’s ἐνέργεια is present in Paul and comes to expression in his own ἐνέργεια. And if ἐνέργεια is, as Aristotle thinks, identical to “living” (ζάω), then it comes as no surprise that Paul says that Christ lives (ζάω) in him in such a way that his own living (ζάω) is established thereby.

Furthermore, if Aristotle understood that for Paul God has acted upon believers by saving them, it would come as no surprise that Paul exhorts the Philippians to “work out your own salvation … for God is the one who works in you (ὁ ἐνεργῶν ἐν ὑμῖν) both to will and to work” (Phil 2.13). From Aristotle’s perspective, there is no “tension” or “paradox” between divine and human agency: if God has radically altered believers’ existence, then for Aristotle it would necessarily be the case that God’s ἐνέργεια is present in them in such a way that it does not cancel out their own ἐνέργεια but actually brings about their virtuous actions (their own ἐνέργεια). In this case, divine and human agency are “non-contrastive”—not because this is how God operates everywhere, but because he has uniquely determined the existence of believers through his own ἐνέργεια.

And finally, if Aristotle thought that Christ’s ἐνέργεια is present in believers, then he would probably conclude that they, in some way or another, share the same being. Aristotle would probably understand our language about “being in Christ,” but he wouldn’t be able to affirm this unless believers were acting in Christ, since the connection between Christ and believers is established through activity. Now, to say that they share the same being is not to say that they are altogether identical; but if uniting ἐνέργεια means uniting being, then that means Christ and believers are fundamentally ontologically united with one another through their unified action. While Aristotle might not use Paul’s precise language, he might be sympathetic to Paul’s claim that believers now comprise the body of Christ (1 Cor 12.27).

None of this is to suggest that Paul has an Aristotelian ontology or anything of the sort. But Aristotle’s configuration of relationships and ἐνέργεια might help us see that some of the things that might seem perplexing to us at first glance—statements about double agency or shared being in Christ—might make a bit more sense when read with Aristotelian eyes.

The Select Works of Aristotle, which includes 40 volumes of the great philosopher’s works, is finally being shipped next week for the Logos digital library.

Take advantage of the extra-low pre-publication price now before it goes up on Monday, and gain an uncompromisingly efficient resource for your research efforts and reading pleasure.