Write what you see in a book and send it to the seven churches, to Ephesus and to Smyrna and to Pergamum and to Thyatira and to Sardis and to Philadelphia and to Laodicea. (Rev 1:11)

The apostle John, the author of Revelation, obeyed God’s instruction in this verse to write down and send what he “saw”—along with the oracles that follow in Revelation 2 and 3—all from while imprisoned on the island of Patmos. These seven cities in Revelation 1:11 were part of an itinerary first followed by John’s messenger who took the scroll—John’s Revelation—from congregation to congregation.

Many pilgrims today follow that same itinerary seeking to immerse themselves in the contexts of Revelation’s audience.

In this excerpted transcript from the Mobile Ed course The Seven Cities of Revelation, instructor Dr. David deSilva explores what the island of Patmos was like when John lived there—as well as what it is like today.

***

Juvenal, the Roman satirist, active toward the end of the first century AD, describes several Greek islands that are near to Patmos as “rocks crowded with our noble exiles.” While Juvenal does not mention Patmos specifically, this smallish island, no more than 30 miles in circumference, might well also have served such a function, a place to which to send largely elite undesirables, removing them from their places of influence where they might foment trouble or otherwise cause embarrassment for Rome and its leaders.

If our image of the island of Patmos, or especially John on Patmos, is the image of a lonely man on a rocky island, we need to revise that image considerably. Patmos was a regular stop on maritime trade routes between Asia Minor or other eastern Mediterranean points of origin and Greece. The island itself, having a very uneven coast, offered many natural harbors to ships carrying goods back and forth between the two sides of this body of water.

It was, in fact, inhabited by many families throughout the Hellenistic and the Roman periods, to judge from funerary monuments that have been discovered throughout the island. . . . no physical evidence [exists] of mines or a penal colony on Patmos, calling into question the traditional image of John having been exiled to Patmos in connection with being condemned to a mine or a particular prison. Rather it appears that he would have suffered relegation to an island as punishment, a form of exile, removing a dissident whom it was not convenient to execute for one reason or another.

The remains of this fortress are scant. This is the result of a practice that has ravaged archaeological sites across the Mediterranean over the centuries. That process is, simply, recycling. Nothing is so attractive to the next century of builders as a pile of precut stones from a derelict building ready to be repurposed in some new construction. So throughout the Mediterranean and throughout the cities that we’ll be visiting in this course, we will see what such repurposers have left behind for posterity to see. However, the footprint of this fortress is still clearly visible, and it suggests a once-imposing and extensive structure on the top of this mountain.

Second-century BC gymnasium

A number of other archaeological finds testify to the liveliness, to some extent, of Patmos as an island. An inscription bears witness to the presence of a gymnasium from the second-century BC and following. A gymnasium was a place for the practice, of course, of Greek athletic games and training and keeping oneself in shape. The Greeks were . . . a major cultural force in drawing attention to such things throughout the Mediterranean. But a gymnasium was also typically a place for the education of the young, training them in all the facets of the Greek curriculum including logic, rhetoric, grammar, astronomy, geometry, music, and the rest.

Hellenistic period garrison

Visitors to Patmos can see the remains of a large Hellenistic-period garrison on the top of Mount Kastelli. This had been built primarily to protect the shipping lanes from piracy. From this altitude, lookouts could keep an eye on the ships coming in and out of Patmos’ ports and intervene if there was any criminal activity threatening the flow of trade east and west.

So the presence of a gymnasium indicates the presence of a larger well-functioning society of families continuing to inculcate the next generation in the Greek way of life. This particular inscription speaks of an association of torch runners, a kind of club within the gymnasium, who participated in a sacred race to take fire to an altar of Hermes on the island. This altar to Hermes, who was the patron god of gymnasia, is yet undiscovered.

Temple of Artemis

The landscape of Patmos is currently dominated by the Monastery of Saint John, founded in the eleventh century. Of course, the monastery is named after John to commemorate the John who wrote Revelation from this island.

The monastery itself, however, set on a hill opposite Mount Kastelli, is built over the foundations of an ancient temple to Artemis. An inscription found on the island speaks of a priestess of Artemis named Bera or Vera and a temple of Artemis on the island, which is here called “the most noble island of Leto’s daughter,” Leto being the mother of both Artemis and Apollo.

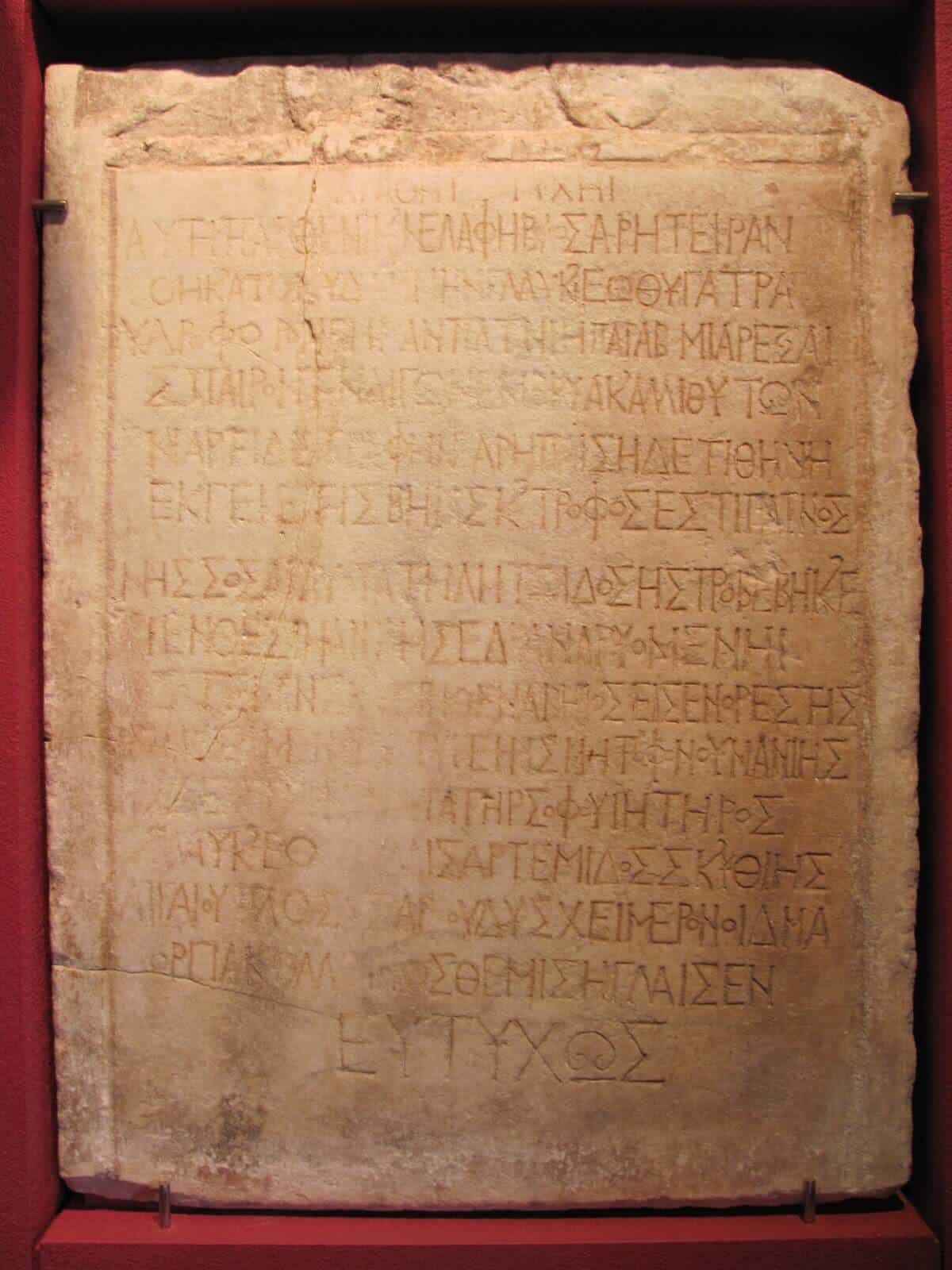

An inscription [below image] was also found on part of an altar under the monastery complex naming Artemis Patmia (Artemis of Patmos) as the dedicatee of the temple there.

Temple of Apollo

There were also major temples of Artemis, of course, on the mainland, but also Apollo, her brother, in Miletus, of which Patmos was a kind of satellite island falling within its administrative jurisdiction, and also a grand temple to Apollo at Didyma, near to both Miletus and Ephesus.

There was a famous oracle of Apollo at Didyma. Apollo was closely linked with prophecy throughout the ancient world. Apollo’s oracles would be consulted by elites and occasionally non-elites on matters of politics and strategy and policy, and the oracle would give cryptic responses, which were received as messages from the god himself.

It has been suggested that there was also once a shrine or temple to Apollo that was part of the complex on Mount Kastelli, standing there as an appropriate counterpart to the temple of his sister Artemis on the opposite mountaintop. The Acts of John, an apocryphal text from the fifth century, speaks of a temple and priests of Apollo on the island also.

Reconfiguration of Apollo mythology

The myths of Apollo and his human mother Leto, and Python, an evil adversary of the gods, may stand behind John’s reconfiguration of this myth in Rev 12, where now he presents Christ as the divine figure and the dragon Satan in the place of the dragon (or the great snake) Python as the antagonist of this divine birth. And it’s also been suggested that Apollo, as a focal point of prophecy in the ancient world, is figured in the rider with a bow on the white horse that goes forth with the opening of the first seal. On this reading, that first seal unleashes false prophecy—perhaps even specifically the false prophecies that were said to have been uttered about Rome and Augustus and the destiny of each.

Contrary to the public discourse about Rome and Augustus, John’s message would counter that their rise did not mean peace and prosperity for the world, but rather civil war, bloodshed, famine, and pestilence.

***

To learn more, get The Seven Cities of Revelation, which combines lectures and photographs to bring the island of Patmos and the seven ancient cities of Revelation 2–3 to life. The course discusses the archaeological remains of each location, shedding light on the cultural context of the book of Revelation.

Related articles

- Consistent Inconsistency in the Book of Revelation

- 4 Keys to Kindling Your Love for the Book of Revelation

- 3 Mistakes Most People Make When Reading Revelation