English philosopher Francis Bacon wrote, “The monuments of wit survive the monuments of power.” In other words, while the trappings of power may decay, works of wit endure.

Among these works of wit is satire. Much more than just a joke at another’s expense, satire is the use of humor to expose faults and inspire change.

I love reading classic satirical literature. While appreciating the author’s razor-sharp pen and comical incisions, we get to study the social mores of another culture and era. And, amazingly, works of satire that were written hundreds of years ago still feel incredibly relevant to today, revealing the foibles of humanity that transcend any particular setting.

Among my favorite “monuments of wit” (by three monumentally witty authors!) are Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, and Charles Dickens’ Bleak House.

And best of all, they’re all available right now on Community Pricing!

Jonathan Swift vexes the world

When writing to his friend and fellow satirist Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift stated that his chief goal in writing Gulliver’s Travels was “to vex the world rather than divert it.”

In the unfolding narrative of his travels, Gulliver reminds the reader that his goal is “to relate plain matter(s) of fact in the simplest manner and style.” He takes his encounters with Lilliputians, giants, floating islands, intelligent horses, and the brutish Yahoos in stride—rarely expressing shock.

By presenting the fantastic as ordinary (or mildly unusual at most), Swift creates his first layer of irony. Professor Ernest Tuveson puts it best, stating, “In Gulliver’s Travels there is a constant shuttling back and forth between real and unreal, normal and absurd . . . until our standards of credulity are so relaxed that we are ready to buy a pig in a poke.” No aspect of eighteenth-century England (or human nature in general) is off limits to Swift. He takes what is familiar and makes it foreign. The normal becomes the absurd. He presents a characteristic as sensible, then proceeds to render it senseless.

When discussing Gulliver’s Travels, I’ve often found that no one can agree upon its ultimate message. Is it to lampoon eighteenth-century politics and corruption? To mock the Enlightenment’s devotion to reason and science? Or to show that we’re simply all Yahoos?

On the surface, Gulliver’s Travels is a simple adventure story. But, as one peels back the layers of irony, they’ll find a captivating and complex satire. Having never gone out of print, Gulliver’s Travels has continued to vex readers for over 280 years.

See what all the fuss is about: pick up Gulliver’s Travels and more with Noet’s Select Works of Jonathan Swift. They’re still on Community Pricing—bid now!

Jane Austen examines the relationship between society and literature

Jane Austen is best known for her ironic humor and satire of the British upper class. In Pride and Prejudice, her most popular novel, Austen’s sharp wit is directed toward nineteenth-century English society’s preoccupation with marriage—especially making a “socially advantageous” match.

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.”

In the midst of writing and revising Pride and Prejudice, Austen completed Northanger Abbey, an ironic parody of the sensational Gothic novels that were so popular during her time. Parody—imitating the style of another composition for comical effect—when used to critique, can be an effective vehicle for satire.

In Austen’s parody, the main character, Catherine, loves Gothic novels—the haunted castles, brooding villains, and pale-faced heroines. During her stay at Northanger Abbey, Catherine confuses real life with fiction, expecting the happenings at the abbey to parallel a Gothic novel. She’s in the correct setting—shouldn’t the characters and plot follow? This is especially well illustrated when Catherine believes to have found a secret document:

Her greedy eye glanced rapidly over a page. She started at its import. Could it be possible, or did not her senses play her false? An inventory of linen, in coarse and modern characters seemed all that was before her! . . . Nothing could now be clearer than the absurdity of her recent fancies. To suppose that a manuscript of many generations back could have remained undiscovered in a room such as that, so modern, so habitable! or that she should be the first to possess the skill of unlocking a cabinet. . . .

As Catherine attempts to find the extraordinary in the ordinary, she misidentifies the true threats to her well-being—a false friend, a man obsessed with wealth, and her own naiveté.

Throughout the work, Austen masterfully builds tension and suspense—hallmarks of the Gothic novel—yet, when we peer into the shadows, instead of discovering ghostly apparitions, we find real life. Just like Catherine, we’ve been misdirected by our expectations.

More than just a comic parody, Northanger Abbey is a novel about the relationship between fiction and reality. Austen illustrates that literature’s impact on our worldview is not to be underestimated.

Good news—we’re building a Noet edition of Jane Austen’s novels! Pick up Northanger Abbey and Austen’s other works at the best price.

Charles Dickens crusades against injustice

Among the most famous of Dickens’ works is Bleak House. In this novel, he satirizes a society that is hopelessly indifferent to the human need for empathy, vividly setting the scene with the novel’s first paragraph:

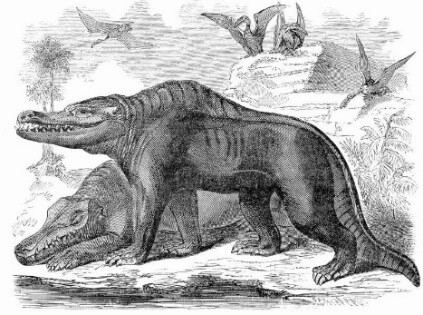

London. Michaelmas Term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets, as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn-hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snow-flakes—gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. . . .

According to American writer and literary critic Edmund Wilson, “Of all the Victorian novelists, [Dickens] was probably the most antagonistic to the Victorian age itself.” Dickens’ novels consistently address the struggles of the poor in nineteenth-century England. Through his masterful portrayals of apathy, greed, and (on a brighter note) the true potential for human goodness, Dickens helped raise awareness and inspire change.

Today, Dickens continues to captivate readers, providing unique insight into the lives of those living on the fringes of Victorian society.

Dickens’ most influential works—including Bleak House—are currently on Community Pricing. Place your bid now!

Study satire with the best research tools for the best price

Jonathan Swift, Jane Austen, and Charles Dickens all employed satire as a clever way to inform and challenge the popular beliefs of their times. Due to their skillful storytelling and timeless themes, their monuments of wit have remained popular and relevant to today’s readers.

With Noet’s smart texts, you can examine satire with unparalleled depth. Compare and contrast Dickens’ influential works, scrolling side by side. Find every mention of “marriage” in Jane Austen’s novels with a single search. Make notes, highlight key phrases, and sync them across devices as you examine Gulliver’s Travels.

Select Works of Jonathan Swift, the Collected Works of Jane Austen, and Select Works of Charles Dickens are all on Community Pricing—bid now!

Then, continue building your library at Noet.com.