Have you ever noticed that when we talk, instead of just saying what we want to say, we’ll often say something about what we’re saying? We use expressions like:

- “I want you to know that . . .”

- “It’s very important that you understand that . . .”

- “Don’t you know that . . .”

Expressions like these are called metacomments. They interrupt the speech by commenting on what’s about to be said, or what’s just been said. We could just as easily leave them out and say what we wanted to say—so why do we use them?

The interruption caused by the metacomment slows down the flow of the discourse, producing a special highlighting effect. Just think about when we use the English expressions listed above. They signal that what we are about to say is important information. Think of them as road flares or speed bumps, telling you to pay attention to what is just ahead.

Believe it or not, metacomments are also used in Scripture. The Lexham Discourse Hebrew Bible and the English High Definition Old Testament use symbols to mark each metacomment.

Metacomments in action

Let’s take a closer look at a metacomment:

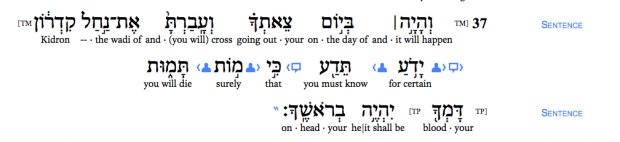

In 1 Kings 2:36–38, King Solomon, adhering to his father David’s final instructions (vv. 2–9), commands that Shimei the Benjaminite be confined to Jerusalem in order to prevent him from marshaling support against the Davidic dynasty. In v. 37, Solomon threatens Shimei with what will happen to him if he attempts to cross the Wadi Kidron and leave Jerusalem:

Notice that the writer could have just said: “. . . on the day you go out and cross over the Wadi Kidron, you will surely die. Your blood will be on your head.” But instead, the author inserts the metacomment: “know for certain that . . .” just before he states the consequence. This has the effect of slowing down the discourse and simultaneously highlighting the severity of the consequences Shimei will face if he tries to flee Jerusalem.

Another example of a metacomment involves the Hebrew phrase yn:∞doa} µ~aun “declares the Lord.” This formula is frequently used in the Prophets to break what might have been one long speech into smaller parts since the original manuscripts lacked chapter and verse divisions. Breaking it into smaller chunks makes it easier for the reader to process. But sometimes we find metacomments like “declares the Lord” used in unexpected places, like the middle of a clause or speech rather than the beginning or end. Placing the metacomment in the middle of the clause interrupts the flow of speech and highlights what comes next. Take a look at the use of yn:∞doa} µ~aun “declares the Lord” in Amos 8.

Amos 8 depicts the Lord’s impending judgment upon Israel. In v. 9, we read:

“And on that day,” declares the Lord GOD, “I will make the sun go down at noon and darken the earth in broad daylight.”

The metacomment “declares the Lord” is unnecessary, since we already know from v. 7 that Yahweh is the one speaking. Inserting this phrase in the middle of the clause interrupts the flow of speech, slowing down the discourse and signaling us to pay special attention to the imagery of divine judgment that follows.

Annotate each metacomment with the LDHB and LHDOT

The Lexham Discourse Hebrew Bible and the Lexham High Definition Old Testament help you dig deeper in your Bible study by annotating each metacomment, as well as 29 other important discourse devices. These resources also include an introduction and glossary to help you understand the function of each device.

Last year we released Genesis–Jeremiah, and now we’re excited to announce the release of Ezekiel–Malachi. When you purchase the LDHB or the LHDOT, you’ll receive Genesis–Malachi; the remaining books will be automatically downloaded to your Logos library as they’re released in the coming months.

If you own either of these resources, you should have already received your update automatically. If you haven’t received your update yet, simply restart your software.

If you don’t already own the Lexham Discourse Hebrew Bible and the Lexham High Definition Old Testament, pick them up today!