If you want to start a fight, meddle with people’s religion and their grammar at the same time.

Here goes.

I think it’s time to no longer capitalize deity pronouns in Christian writing and in (most) Bible translations.

Shall we take this out back?

I feel the weight behind this tradition because I, too, live to honor God and I, too, want to write good English prose.

But we should still let the custom drop. Not only does it muddy our communication with the uninitiated, a similar tradition has robbed us of the knowledge of how to pronounce God’s name.

Why we should not capitalize deity pronouns

Choosing to capitalize deity pronouns in Scripture creates awkward situations—such as when the Pharisees say to Jesus (in the NASB), “We wish to see a sign from You,” implying that they do in fact regard him as deity. This practice forces us to specify whether a given pronoun refers to God in ambiguous cases; it also shouts interpretations that authors may have preferred to whisper (Isa 53:6). And as the Zondervan style guide wisely points out, capitalization in English doesn’t generally mean respect, but specification (see “Pol Pot” and “Satan”). Also, as this capitalization tradition fades—and it is fading—younger readers may interpret a He in the middle of a sentence as emphasis (or, I’d add, as random, Dickinsonesque orthographic noise). Bible translations, and Christian books generally, ought to avoid distraction by sticking to conventions familiar to the largest number of readers possible.

But not everyone is persuaded that tradition ought to yield to accessibility in this case. After I published a column on this subject, two seminary-trained men wrote me (graciously!) with opposite reasons for their disagreement. One insisted that he capitalized deity pronouns not for respect but for clarity, the other that he capitalized them not for clarity but for respect.

Frankly, it’s kind of fun to have a serious disagreement when the stakes are so low. You can engage in all the Kabuki of outraged argument without actually being angry. But the gentleman who did capitalize deity pronouns for respect raised an interesting parallel issue that convinced me even more that I was right (a lovely feeling the internet often affords one). This is where the pronunciation of God’s name comes in.

Even older scribal traditions

Writing a letter to the editor in my own denomination’s magazine (where I had written my column), this pastor said,

I appreciate Dr. Ward’s zeal for clear communication… but I disagree with his call to eliminate the capitalizing of deity pronouns and select nouns.

I can think of two ancient conventions intended to convey reverence that lend support to continuing our tradition of capitalization. In the OT there is the qere perpetuum practice of substituting “Adonai” for YHWH. The Jewish reader would say “Lord” when the text read God’s personal name.

In the NT there was the scribal practice of substituting divine nouns with the special abbreviations called nomina sacra. It was a unique practice that people outside of the Christian community would not have readily understood. Similarly, our typographical tradition of capitalization has become standardized among the Christian community.

No rational reader would see a capitalized pronoun referring to Jesus in the reported speech of Pharisees as an indication that the Pharisees respected Him. It simply indicates that we’re making a small effort in our written documents to show Him reverence.

I’m guessing it’s been a while since the words nomina sacra and qere perpetuum have shown up in a letter to the editor of my denominational magazine. When I saw them, I got excited. I had a serious interlocutor with a cogent point, basically that the tradition I was critiquing was far older than I had considered. Time for some serious Kabuki.

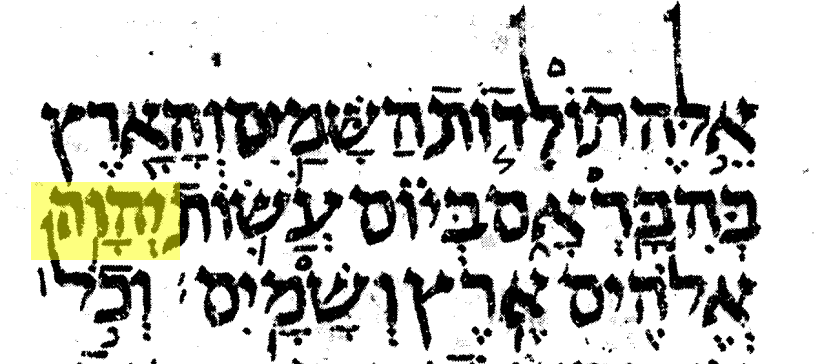

Qere perpetuum is the ancient Jewish practice of retaining the consonants of the covenantal name of God, the tetragrammaton (YHWH, “Lord”), but supplying different vowels, the vowels from adonai, “lord.” Qere perpetuum is an amalgamation of Hebrew and Latin, and it means “always read”; that is, always read this in place of what was originally intended.

Here is the very first instance of the qere perpetuum in the Leningrad Codex, the eleventh century manuscript that provides the basis for modern editions of the Hebrew Bible, at Genesis 2:4 (YHWH is in yellow):

This practice, however, has left us with an odd situation. As the Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary says, “The pronunciation of yhwh as Yahweh is a scholarly guess.” (1011)

The AYBD continues:

Hebrew biblical mss were principally consonantal in spelling until well into the current era. The pronunciation of words was transmitted in a separate oral tradition. . .. Though the consonants [YHWH] remained, the original pronunciation was eventually lost. (1011)

We know the consonants, but we don’t know the vowels. Yes, that’s right: we don’t know for sure how to say the name of our own God (Isa 42:8).

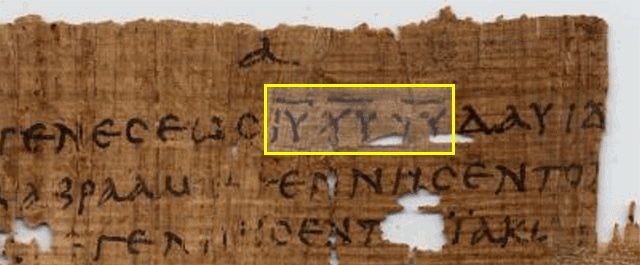

Nomina sacra is the similar Christian practice of abbreviating certain divine names, especially Lord (kurios) but also Jesus, Christ, God, Father, and Spirit—and even cross, crucify, Israel, and Jerusalem. Nomina sacra are visible to this day both in NT manuscripts and in Eastern Orthodox iconography. They show up at the earliest stages of the manuscript tradition. In one of the oldest papyri we have, ?1, there are three nomina sacra in a row in the very first line (ι̅υ̅ χ̅υ̅ υ̅υ̅, Jesus Christ Son):

I’m not aware of any problems caused today by the nomina sacra: we certainly know how to pronounce Jesus (though Larry Hurtado has commented in private correspondence to a friend of mine that the nomina sacra “did amount to a kind of ‘in-house’ convention that outsiders wouldn’t have grasped readily”).

Slicing off the end of the ham

You can look up qere perpetuum and nomina sacra in many resources in Logos, and you should. But if you read a Bible dictionary, you may make the mistake of assuming from the straightforward tone of the article that we know for certain why these scribal practices developed. Philip W. Comfort has a fascinating and detailed discussion of the nomina sacra in his Encountering the Manuscripts: An Introduction to New Testament Paleography and Textual Criticism, and he carefully acknowledges that we simply don’t know how they got started.

Comfort’s highly educated guess is that the nomina sacra were developed on the model of the qere perpetuum in the tetragrammaton. The first Christian scribes may previously have been Jewish scribes. It is therefore “very likely that the first of the nomina sacra was ΚΣ for kurios (Lord).” (207)

The origin story for the qere perpetuum is generally thought to relate to the third commandment and the honor the Jews accord to the divine name. “This name was so sacred to them that they refused to utter it or even spell it out in full when they made copies of Scripture.” (207)

But as with the origin of the qere perpetuum, so with the origin of the nomina sacra. Comfort says: “Definitive proof eludes us.”

That’s what happens with traditions. They get encrusted with new associations that obscure the old ones. And pretty soon your great-granddaughter is slicing off the end of the ham. This doesn’t mean we should jettison all traditions, as if we even could. It does mean that the ad fontes, sola scriptura, semper reformanda impulse of Reformation Christianity makes me suspicious when two very smart people who love the Bible give opposite reasons for maintaining the same capitalization tradition (namely clarity and respect). We’ve reached the encrustation stage. If we’re not sure why we’re doing something, perhaps we need to put the end of the ham back on.

Conclusion

When we have two genuinely valuable things that stand in tension—like clear communication to all English speakers vs. a traditional way of according respect to God’s name—I’m open to keeping both if possible. One way to do that is to consign deity pronoun capitalization, and the capitalization of LORD, and the bolding or small-capsification of OT quotes, and italicization of words supplied by translators, and other specialized Bible-codey stuff to a literal Bible translation or two, like the NASB and LEB, whose readers understand what’s going on and who find these traditions to be helpful shorthand.

But if clarity and tradition truly conflict—as I think they now do in most places where deity pronouns have usually been capitalized—you can guess which one this Protestant thinks should win. Now that we’ve passed the 500th anniversary of the movement, which gave us our explosion of vernacular Bibles around the world, perhaps it’s a good time to no longer capitalize deity pronouns.