Out of the inscrutable neuron maelstroms we know as “the brains of small children,” there often come what speech pathologists call “the darnedest things.” My kindergartener said yesterday—and I promise I have no idea where this came from—“What if ‘Lutheran’ meant ‘disqualified’?”

I immediately took his question down verbatim for future blog use. It’s my job. And because my boy has a wannabe linguist-theologian for a father, my own neuron maelstrom—which, since I’m an adult, is easier to scrute—started whirling . . . What if, indeed?

Well, a lot of church signs would have to come down. Nobody would want to go to Trinity Disqualified of Albuquerque—if that’s what “Lutheran” meant. Attendance would drop off at both DCMS and EDCA congregations. Sales of the Life Works of Martin Disqualify would fall just as precipitously.

My son’s bizarre hypothetical gives me an opportunity to invite one and all to a little soapbox I always keep nearby. You want to know, why do we associate seemingly unrelated noises [like diss-KWAL-if-eyed] with specific meanings? Well I’ll tell you: there is little to no necessary connection between the sounds we utter and the meanings they carry. That connection is made by inherited group convention.

Cue clever pivot to Bible study

Now comes the point at which I’m supposed to cleverly pivot into a lesson about Bible study, and it’s so easy. I could pivot into anywhere in the Bible, anywhere. Because all the words in there are like “Lutheran” and “disqualified”—they bear little to no meaning in and of themselves but instead derive their meaning from the thick webs of convention we call “Hebrew” and “Greek.”

(A partial exception is onomatopoetic words, like buzz or meow, which sound like the things to which they refer. One example from biblical Hebrew is דַּהֲר֖וֹת דַּהֲר֥וֹת: da-hu-rōt, da-hu-rōt—“galloping, galloping” in Judges 5:22. But even there, we say in English “gallop,” not da-hu-rōt—there is still a strong conventional element in the formation of each word. Dogs bow-wow in English; in Spanish they guau-guau.)

Understand, in saying all this, I’m not saying that biblical words are meaningless or that we can impute whatever meaning we want to them. That’s the sin of the serpent in the Garden (“Yea, hath God said?”). I’m saying that it matters how we think we get at the meaning of words. If you assume that there is some sort of necessary connection between a word and its meaning—that the sounds L+OO+TH+R+I+N must always and only refer to the church which has descended from the Magisterial Reformer—you’re going to risk confusion when you come to your Bible. Because the Bible uses words the same way we do: with flexibility constrained by context.

Disqualified

Let’s take a look at the Koine Greek (near-)equivalent of one of the words my son mentioned. No, not λύθεραν (lutheran—not a real word), but ἀδόκιμος (adokimos—“disqualified”). That particular set of sounds—A+D+O+K+I+M+O+S—is used even within the NT to refer to a flexible, though not limitless, set of ideas.

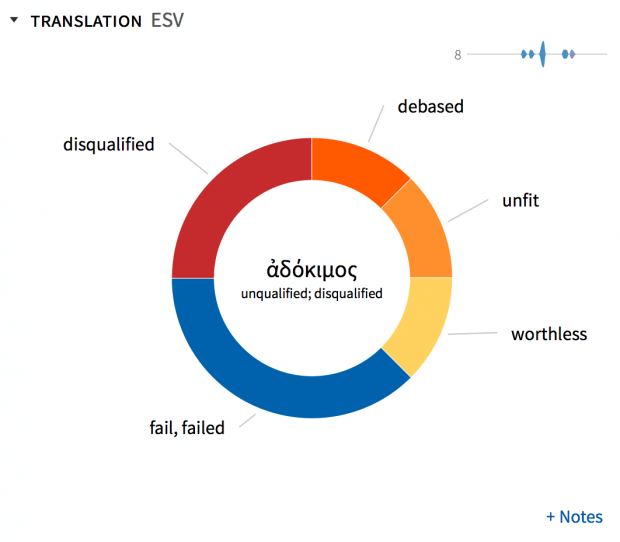

My Bible Word Study tool in Logos tells me that the ESV translates the word in several significantly different (but still apparently similar) ways:

The Bible Word Study also tells me that the Septuagint uses the word in yet another way, to refer to silver dross:

On first glance, I was guessing that “dross” may have been the original meaning of ἀδόκιμος, and “worthless” may have been the metaphorical derivative that eventually took over. That happens often in language. A little further thinking and study shows that my guess was forehead-slappingly wrong; the word clearly comes from a combination of “not” (a-) and “tested” (dokimazo) (which itself goes back to “show,” dechomai). Ah, well. “Dross” still provides a rich word picture, an illustration for the word that I could use in teaching.

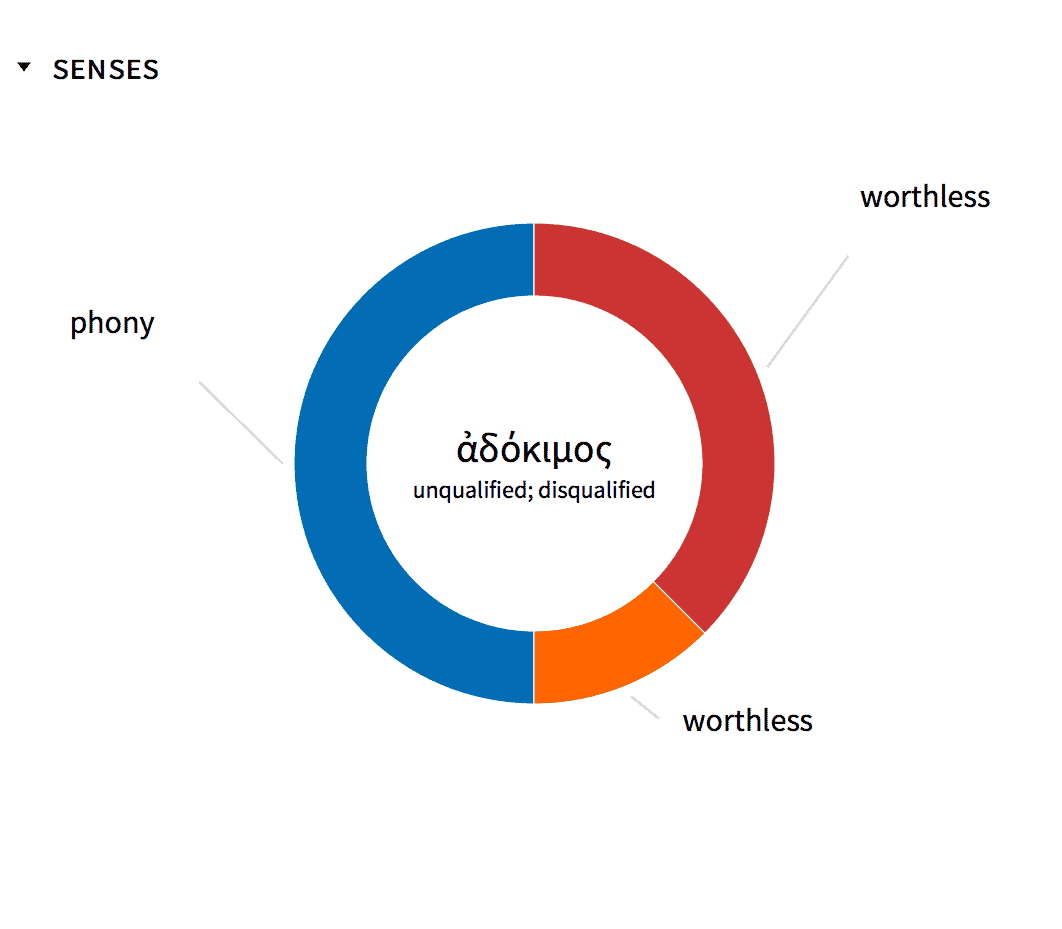

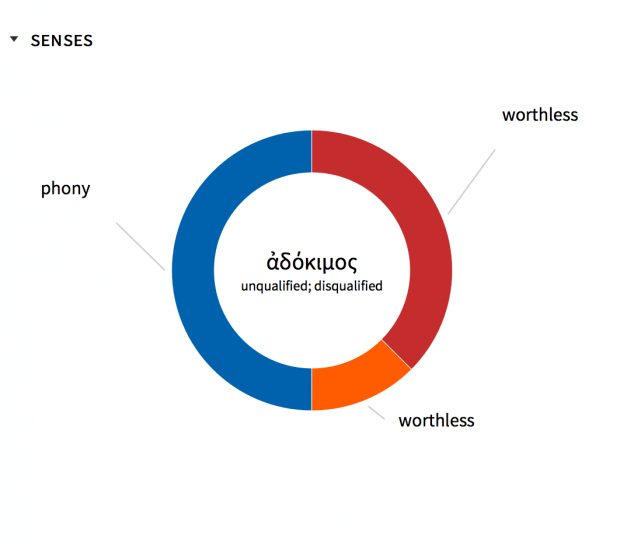

The Bible Sense Lexicon offers two major senses, “phony” and “worthless” (the latter is divided into moral and non-moral senses, hence the two sections on the chart):

This word ἀδόκιμος (adokimos) cannot mean precisely the same thing everywhere it appears. Take just three examples:

- If [farmland] bears thorns and thistles, it is worthless and near to being cursed, and its end is to be burned. (Heb 6:8)

- Since they did not see fit to acknowledge God, God gave them up to a debased mind to do what ought not to be done. (Rom 1:28)

- I discipline my body and keep it under control, lest after preaching to others I myself should be disqualified. (1 Cor 9:27)

There’s more than a family resemblance in all three of these uses; we’re dealing with the same Greek word. But the contextual emphases are noticeably different, and they foreground different potentials within the word.

- Farmland (example 1) can’t be morally “debased.”

- And sinners (example 2) aren’t “worthless” (all God’s image-bearers, no matter how depraved, bear genuine worth).

- And Paul in 1 Corinthians 9 (example 3) uses an athletic metaphor for which “disqualified” is a particularly suitable English equivalent; he’s not afraid of being “worthless” or “debased.”

Our English word “disqualified” is probably not quite as flexible as adokimos. But it has enough flexibility that, like adokimos, it can be used to speak of both moral and non-moral disqualification. You can be “disqualified” from the runnings for the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame because of gambling on games, and you can be “disqualified” from military service because of a heart murmur. Context tells you which kind of disqualification is intended.

There’s science involved in finding that out what a word means in a given context; it’s helpful, at the very least, to understand a little about how language works. Fundamentally, I have to be able to separate in my mind a word and the concept to which it refers. If I insist that “Lutheran” can never mean “disqualified,” not in a million years—because it just can’t, or because the dictionary—I’m going to have a hard time understanding how Paul could do what he does with ἀδόκιμος. I need to be ready for some flexibility in word usage, even and especially in the Bible. I say this not in order to destabilize the Bible but to help establish how clear God intends to be in any give case. There are some things in Scripture that are “hard to be understood” (2 Pet 3:16); God says so, and he designed it that way. It’s okay to admit it. Sometimes clarity is hard-won.

Because there’s art involved in Bible interpretation, too. Weighing all of the interpretive factors in a given context is something I don’t think we’ll ever teach computers to do. Understanding language is an image-of-God thing.

Conclusion

What if “Lutheran” meant “Disqualified”? One important answer to this question is: it could some day. The Chinese famously make the two sounds in ma (M+AH) mean a whole lot of things we English speakers never mean by them. Why can’t the set of six sounds L+OO+TH+R+I+N (seven if you add a schwa sound [ə] in there between the TH and the R) conventionally come to mean what we now mean by “disqualified”? It may seem unlikely, but given the way language works, it is theoretically possible.

Perhaps my son is a prophet, his question a linguistic harbinger. Perhaps this blog post will go viral, he and I will create a meme, and in fifty years, newspaper headlines will read, “Lance Armstrong Lutheraned from Seniors Charity Bike Race After Doping Test.” Stranger things have happened in language.

Mark L. Ward, Jr. received his PhD from Bob Jones University in 2012; he now serves the church as a Logos Pro. He is the author of multiple high school Bible textbooks, including Biblical Worldview: Creation, Fall, Redemption.

Related Articles

29 Bible Study Tools for Reading the Bible More Effectively

How to Study the Bible: 9 Tips to Get More Out of Your Study