In the twenty-five-plus years I’ve led and participated in Bible studies, the most-asked question by far—by both new Bible readers and longtime students of the Bible—is what the best Bible translation is. And every time I’m asked, I always wish I had a simple answer!

Perhaps the better question is: What is the best Bible translation for me right now?

Before I try to offer an answer (and hopefully, equip you to help answer that for others too), we’ll explore the basics of Bible translations. You can start reading from the top or skip to the topics about Bible translations that most interest you.

What is Bible translation?

The history of Bible translation

How do manuscript differences affect Bible translation?

Types of Bible translation

Is one translation strategy better than the other?

How to choose the best Bible translation for you

The value of different Bible translations

How to choose a translation for the task

What is the best Bible translation for you right now?

Bible translation FAQ

What is Bible translation?

The following section is excerpted from Lexham Bible Dictionary.

Bible translation means to restate the meaning of words in one language with words from another. Translation of Scripture is part of the work of interpreting and communicating it.1

This means some portion of the Bible has been translated into 3,415 languages.

But approximately 3,945 languages still need Scripture—which means the people who speak these languages are not able to read God’s Word in their native tongue.2

Because the Bible is more than a book of antiquated stories about wars and relationships—it’s the living, breathing Word of God with the power to transform hearts and minds—translating the original language manuscripts into these 3,945 languages is critical.

The history of Bible translation

Bible translations aren’t new. They’ve been around since before Christ. In fact, in the fifth century BC, after the priest Hilkiah rediscovered the book of the law of Moses in the temple (see 2 Kings 22:8), the Levites stood before God’s people and read the Scriptures aloud. Nehemiah 8:8 says:

They read from the book, from the Law of God, clearly, and they gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading.

The New International Version (NIV) says the priests “clearly explained the meaning of what was being read,” and the Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB) says they read the book of the law of God “translating and giving the meaning.” Thus, they were explaining the first five books of the Bible for the people in a way they could comprehend.

They were translating.

In the third century BC, Jews produced what’s known as the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament for the Greek-speaking Jews living in Alexandria, Egypt. Ron Rhodes writes that this translation “solved a big problem” because “many of the Jews who grew up in these cities could no longer speak Hebrew, but only Greek.”3

Bible translation took off in the first century, Rhodes writes, as early followers of Jesus obeyed his words to “make disciples of all nations”:

Early in biblical history, Syriac or Aramaic translations of the Bible became increasingly important as Christianity spread throughout Central Asia, India, and China. As Christianity continued to spread even further, the need developed for Egyptian (Coptic), Ethiopic, Gothic (Germanic), Armenian, and Arabic translations.

Because Latin emerged as the common language in many parts of the Roman Empire, a man by the name of Jerome was commissioned by the Bishop of Rome to translate the Scriptures into Latin in AD 382. This translation continued to be an unofficial standard text of the Bible throughout the Middle Ages.4

Latin, however, slowly became the Romance languages (Italian, Spanish, French, Romanian, etc.) and ceased to be the common language of the European people. Latin hung on as a scholarly and ecclesiastical (the two things were not distinguished at the time) language, which meant the Church depended on clergy to communicate biblical truth. The Latin translation was called the “Vulgate,” the “common” Bible. But it was not until the fifteenth-century rise of vernacular languages and the invention of the printing press that most “common folk” could again read Scripture for themselves. (More on this below.)

John Wycliffe—an English philosopher, theologian, reformer, priest, seminary professor at the University of Oxford and an advocate for translating the Bible into common language—finished his English translation in 1382. Unfortunately, he worked from Jerome’s Latin Vulgate instead of the original Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek texts, which led to translation shortcomings.

William Tyndale would be the first to translate the Bible into English from the original Hebrew and Greek (though technically, Myles Coverdale was the one who completed the full translation of that Bible after Tyndale’s death) in 1535. For his work, Tyndale was burned at the stake. His crime? Heresy. But his efforts were not in vain. Ryken says just over 80 percent of the King James Bible is essentially Tyndale’s work.5

Other translations followed, like Matthew’s Bible (1537) and the Great Bible (1539).6 The Geneva Bible (1557), translated from the original Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek, would become the official Bible of the Church of Scotland. Leyland Ryken writes that this Bible “quickly became the household Bible of English-speaking Protestants, and it was the Bible used by Shakespeare and carried to America on the Mayflower.”7

It would undergo no less than 140 editions over the next 100 years until “dethroned” by the King James Bible translation.

And from there? Fast forward to modern-day, where Bible readers can choose among about 10 major English translation options. (More on the most-read and popular of these below.)

Learn more about Bible translations in these resources.

How do manuscript differences affect Bible translation?

Mark Ward offers an answer in his article “How to Choose a Bible Translation That’s Right for You”:

The Bibles we read today are based on thousands of ancient manuscripts written in Hebrew and Greek. But no two manuscripts of the Greek New Testament of any length are precisely the same. The story is rather complicated, but the result is this: all modern translations of the New Testament are based on two slightly different editions of the Greek New Testament. The King James Version, New King James Version, and Modern English Version use one edition of the Greek New Testament; the other major English versions (such as the English Standard Version, New International Version, and New Living Translation) all use another. The three passages where the most significant differences occur are Mark 16:9–20; John 7:53–8:11; and 1 John 5:7.8

Types of Bible translations

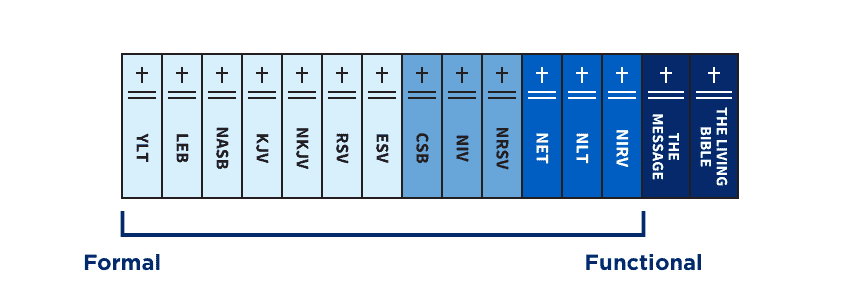

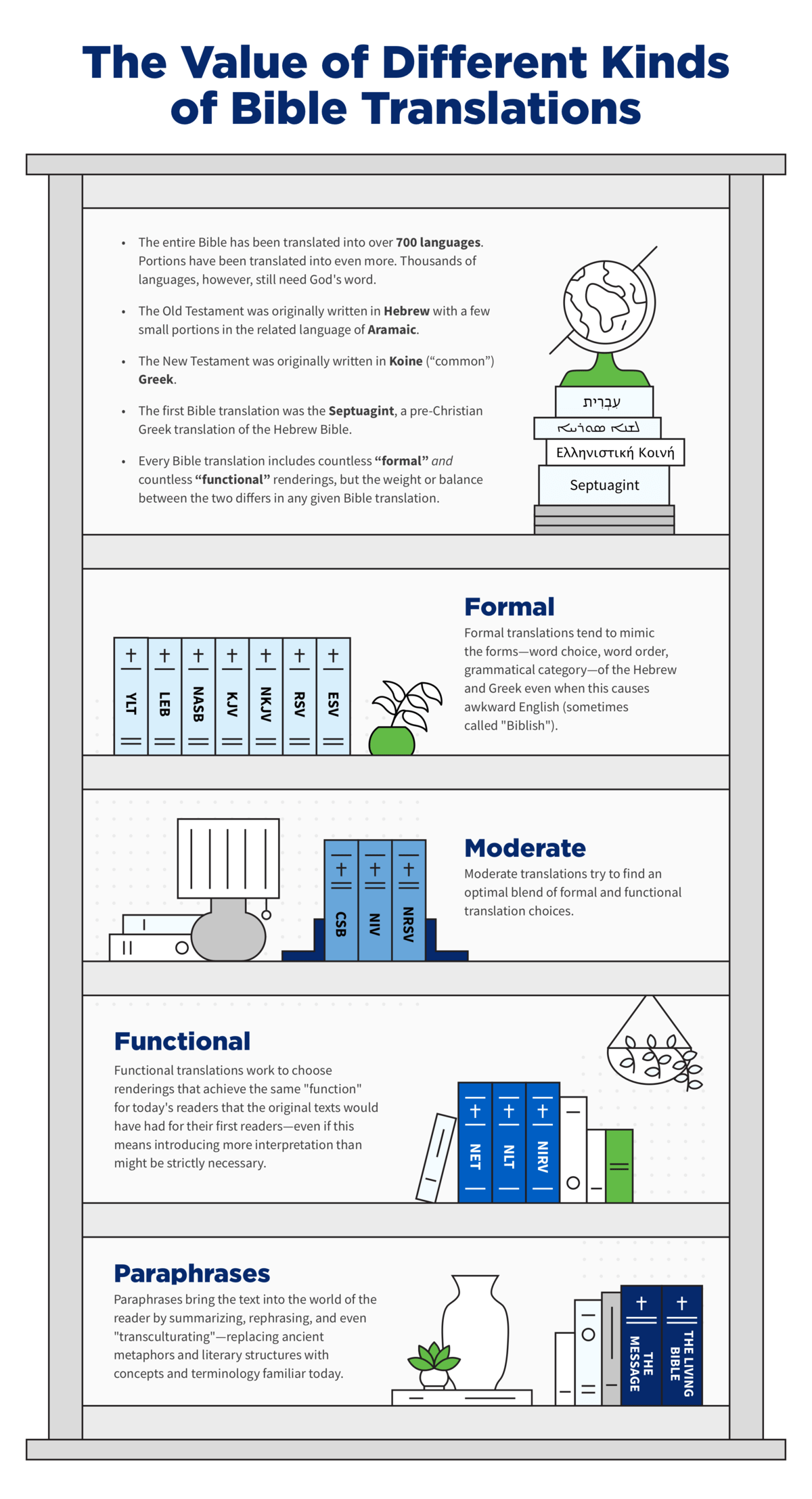

According to BibleProject, every translation balances two goals: faithfulness to the wording of the original language and readability in everyday English. Those two priorities have led to translations that lean more toward one or the other—or fall somewhere in the middle.

Note: As you read the descriptions below, remember that no Bible translation is 100 percent formal or 100 percent functional. It’s more helpful to think of these translation types as points along a line rather than a simple yes or no answer.

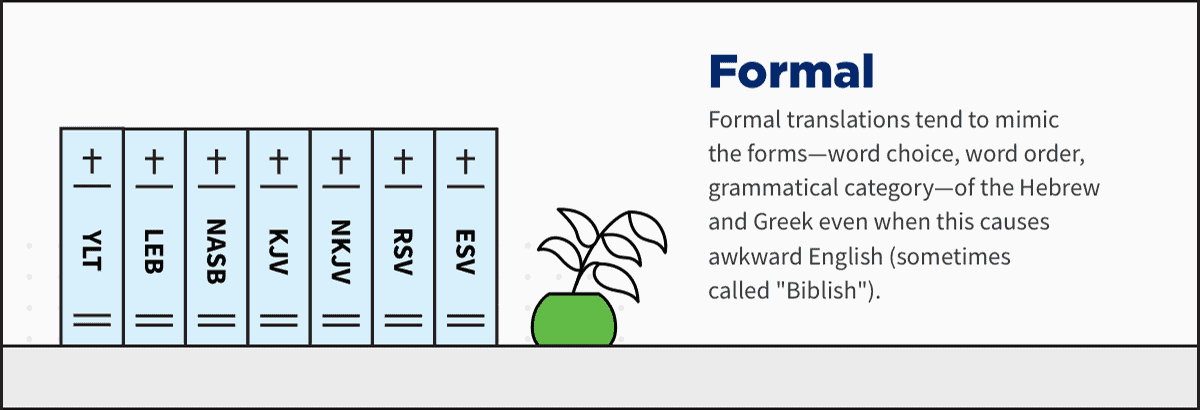

Formal translations

Those that prioritize, as much as English allows, mimicking the forms of the original Hebrew and Greek are known as formal translations; they use an approach to translation called “formal equivalence.”

However, because they generally attempt to choose one English word for each original-language word, and because they try to keep the order of words as close to the original as possible, these translations tend to be more “wooden.” The reading can be a bit . . . bumpy.

For every new translation, a gap of thousands of years exists between now and the time when the authors penned the original manuscripts. Our modern-day culture is dramatically different. Idioms and cultural artifacts and religious practices existed back then that make us scratch our heads. Language, also, has evolved. So naturally, some words or phrasing in formal translations can be awkward to read or nearly impossible to understand in our context. We never say, “Behold!” or “Lo!”

The Lexham English Bible (free with the Logos Bible study app), New American Standard Bible (NASB), King James Version (KJV), New King James Version (NKJV), and English Standard Version (ESV) are some popular formal translations.

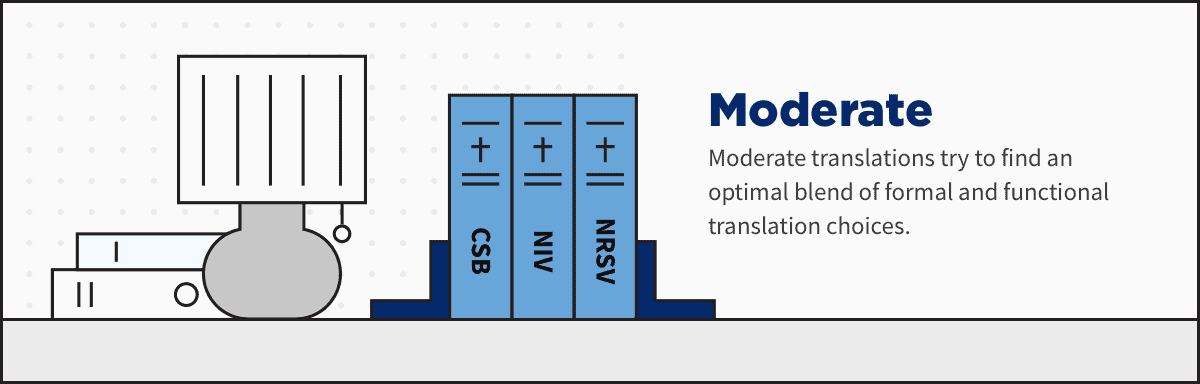

Moderate

Moderate translations try to find an optimal blend of formal and functional translation choices.

The Christian Standard Bible (CSB), New International Version (NIV), and New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) are three moderate translations.

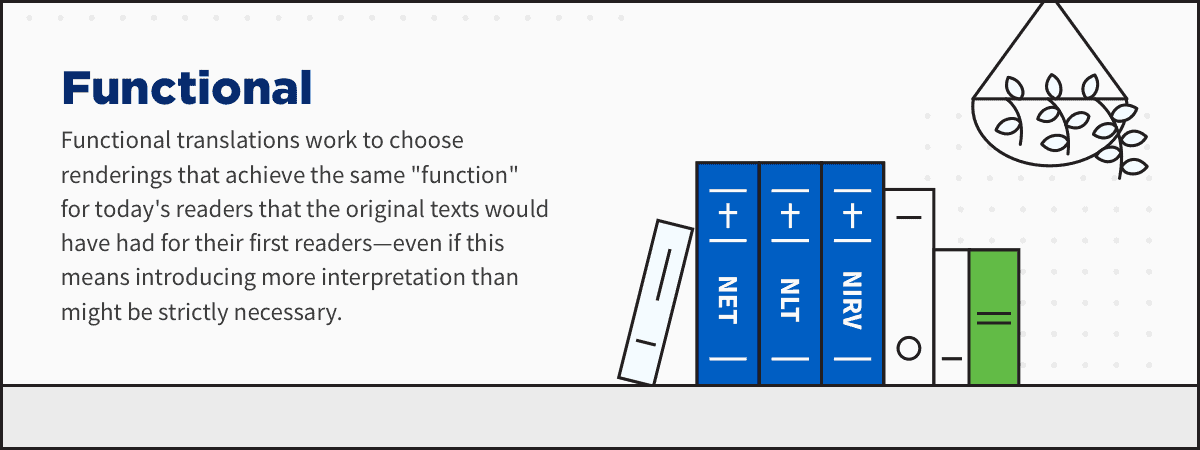

Functional translations

Sometimes referred to as “meaning-for-meaning translations” or “functionally equivalent” versions, functional translations prioritize readability. They attempt to discover the meaning of a text from its form and then translate it to impact modern readers in the same way the ancient text would have affected original readers.

However, though they provide an easy-to-read version of Scripture (and thus tend to be easier to understand), they do this by occasionally being a bit freer to interpret than formal translations are. Meaning and form are not entirely separable; sometimes the original author may have intended more than one meaning. More functionally equivalent versions can sometimes erase inspired ambiguities in the originals.

The New English Translation (NET), New Living Translation (NLT), and New International Reader’s Version are three popular functional translations.

Paraphrases

Some translations are not true translations but rather paraphrases intended to make language even easier to understand than functional Bibles. Mark Ward writes that these versions include “transculturations” of Scripture—replacing ancient metaphors and literary structures with concepts and terminology familiar today. They, therefore, go beyond the formal and functional spectrum. This means they “put Scripture in highly interpretive and very contemporary language.”9

Ward writes:

The most famous paraphrase is The Message, by Eugene Peterson. He has the apostle Peter and Moses and even Jesus talking like modern English speakers. Readers who regard this as sacrilegious are misunderstanding Peterson’s intent—and missing a useful and stimulating Bible study and devotional tool. No, a paraphrase is not “a Bible.” It’s not intended to be. But you still ought to have one on your Bible shelf. Pick it up once you have a pretty good understanding.10

As Ward says, paraphrases are particularly helpful for those who know the Bible well and could benefit from reading Scripture in a fresh way.

Examples of paraphrased Bibles include The Living Bible and The Message.

In this video, Andrew Naselli further unpacks the differences between formal and functional translations, as well as paraphrases:

Is one translation strategy better than the other?

Dave Brunn, author of One Bible, Many Versions: Are All Translations Created Equal? says no, that neither is mutually exclusive or mutually contradictory but are instead “mutually complementary—even mutually dependent.”11

Brunn writes, “When a translator tries to be more precise on one level, such as the word level, it tends to make the translation less precise on other levels.”12

Thus, according to Brunn, each translation has its strengths and limitations”—but also balance each other out.

To illustrate what he means, Brunn references a telescope, a microscope, and a wide-angle lens:

Which of these three ocular instruments gives the best and truest perspective? . . . Obviously, each one is valuable in its own way, and each makes a distinct contribution toward helping us understand the world around us. A microscope does not eliminate the need for having a telescope. And a telescope does not eliminate the need for a wide-angle lens. These three instruments are not in competition with one another—vying for the position of greatest significance. Instead, they complement and balance one another. Each one increases the value of the others.13

So, too, are the many versions of the Bible. “If we understand the translation goals of the various English versions and how they complement each other,” Brunn says, “that can help us glean the full richness of meaning God intended.”14

How to choose the best Bible translation for you

Dear Bible student, keep in mind, you aren’t limited to just one translation—so take the pressure of finding the best Bible translation off your shoulders. Ultimately, the “best” Bible translation for you is the one(s) you’ll read.

If you have difficulty following the phrasing of the NASB, you might enjoy the NIV instead. (Most modern translations are actually really good, especially when you read a few of them.) “English speakers are looking for the wrong thing when we look for best,” writes Ward, who says we should instead be looking for useful: Which English Bible translation is most useful for preaching? For evangelism? For reading through in a year? Which is conducive to close study? How about for reading to kids? For memorization?15Dear Bible student, keep in mind, you aren't limited to just one translation—so take the pressure of finding the best Bible translation off your shoulders. Ultimately, the “best” Bible translation for you is the one(s) you’ll read. Share on X

To help you visualize and better grasp different types of translations, explore the graphic below that shows where some of the more popular translations fall on the “translation spectrum”:

It’s good to have a primary version (some people choose to use the version their church uses), but using many translations while you study will give you a well-rounded understanding of the text at hand.

And with modern technology, this doesn’t mean bouncing back and forth between a tableful of thick Bibles open to your passage (super time-consuming—and that’s if you own multiple print Bibles in different translations!). With Logos Bible Software’s Text Comparison Tool, you can instantly compare any passage in any version of the Bible in your Logos library. It’s fantastic (I glory over how it gives me a different perspective on the passage I’m studying with just a few clicks).

See how it works:

Choosing a translation can be a bit of a process (and many people find it takes time to pull the trigger!). Here’s a few tips:

- Learn the differences between various Bible translations.

- Consider how you will be using the Bible. Will it be your primary Bible or a supplemental Bible?

- Ask a trusted mentor. This likely means your pastor. And that likely means you start with whatever your pastor uses. There’s nothing wrong with this. Your pastor is not perfect, but your pastor is your God-given shepherd.

- New to Bible study? Consider a translation focused on meaning, one that is easy to read.

- Looking for a supplemental Bible to go deeper with your study? Consider one that is the opposite of your primary Bible. (For example, if your primary version is formal, choose a functional Bible.)

Compare translations with these Bible

translation bundles.

Functional (Thought-for-Thought) Bible Translation Bundle 1, 5 vols.

Regular price: $39.99

Mixed Translation Equivalence (Formal and Functional) Bible Bundle 2

Regular price: $32.99

Mixed Translation Equivalence (Formal and Functional) Bible Bundle 1, 6 vols.

Regular price: $39.99

How to choose a translation for the task

You might be a big fan of the New American Standard Bible (NASB), valuing how literal its translation of the original languages is. But that same literal wording might make it a poor choice for reading to your kids. Every Bible has its particular strengths; if they didn’t, then we wouldn’t have so many translations. Those strengths make them well-suited to different tasks. So the first step in choosing a translation is knowing what task you want to accomplish.

While there are many different tasks we may seek to accomplish, in this section we’ll quickly discuss three by way of example:

- Reading large chunks quickly

- Teaching emerging or struggling readers

- Close study of Scripture

Reading large chunks quickly

If you’re looking to read through large chunks of Scripture quickly, it’s important to choose a translation that eases you along. You don’t want to be stumbling over word order when you could be reading text that more closely mirrors the way people talk today. Here are a two recommendations of translations that aren’t likely to trip you up in your extended readings:

- New International Version (NIV)

- Christian Standard Bible (CSB)

Teaching emerging or struggling readers

When it comes to emerging or struggling readers, difficult language can present a huge obstacle both to their understanding and enjoyment of reading. So selecting a translation that simplifies the language and shortens the sentences can help to engage readers who might otherwise be put off. Here’s a good place to start:

Close study of Scripture

In all honesty, everyone has a perspective, and when it comes to Bible translation, even the most literal translations on the market must do some interpretation. Even so, they should try to be objective and present their translation with the minimum amount of interpretation necessary. Choosing to present an ancient metaphor as it was written rather than putting it into a modern idiom is one example of how this can be done. These translations are particularly helpful for closer reading:

- Lexham English Bible (LEB)

- English Standard Version (ESV)

- New American Standard Bible (NASB)

- King James Version (KJV)

So what is the best Bible translation for you right now?

As Mark Ward says, the best Bible translation is “all the good ones.” (There’s only benefit to using multiple translations.) But if you are trying to decide on one, whichever Bible translation you choose, make sure you pick one that you will actually use, read, and study.

With Logos Fundamentals (just $49.99), not only do you get the Text Comparison Tool (you’ll be able to instantly compare multiple texts and quickly spot similarities and differences), but you get four Bible translations to help you do it, including the Lexham English Bible.

Buying individual hard copies of these Bibles could run you a few hundred dollars. But having them all in Logos gives you a much lower price AND makes them portable, so you don’t have to pack a trunk full of Bibles to explore different translations when you’re traveling or running errands or studying at a coffee shop.

(Plus you get the Faithlife Study Bible, audio Bibles, commentaries, Bible dictionaries and encyclopedias, devotionals, and theological works.)

Learn more about Logos Fundamentals.

Bible translation FAQ

We asked our resident Bible translation enthusiast, Dr. Mark Ward, to answer questions the internet has about Bible translation. Mark is the author of Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible (which D. A. Carson called “highly recommended”) and the editor of Faithlife’s Bible Study Magazine.

Click the topics below that interest you to read more.

Which is the most accurate Bible translation?

There are thousands of Bible translations in hundreds of languages. God only—literally God himself only—knows which translation is the “most accurate.” And I’m not being obtuse; I think it’s important to acknowledge what it would take to judge one translation to stand at the top of the accuracy charts: it would mean that in the countless thousands of little choices that Bible translators must make (How should I render this obscure Hebrew word? Is this Greek word given for emphasis or for clarity?), one group of translators got more of their choices “right” than any other group of translators. And how likely is that?

Let me tell you: it’s not. Even if it did happen, there are no God-given—or even humanly agreed-upon—standards by which one translation can be judged to be “more accurate” than another. Non-specialists tend to assume that “literal” translations are more accurate, but that simply isn’t, well, accurate. Literal translation is a valuable tool that all translators use, but no translation is or could be consistently literal, word for word. Language simply doesn’t work like that. So every single translation in existence uses literal and nonliteral renderings.

We could have a “most accurate” Bible translation only if God’s Spirit nudged or “inspired” one set of translators as opposed to others. And he has not said he would do this, nor has he given us any means by which to discern who his specially anointed translators might be. There is no “most accurate” English Bible.

Is the King James Bible the most accurate translation?

The translators of the venerable King James Version went out of their way to insist that their work was not a special work of the Spirit. They asked (and I paraphrase),

Apart from things done by apostles, made infallible by an extraordinary measure of God’s Spirit, what man-made thing exists under the sun that is truly perfect?

Their answer was a decided “nothing.” God hasn’t promised us perfect Bible translations, or even accurate ones. There are languages out there that have no Bible translations, and I have certainly heard (though, by the nature of the case, I could not personally verify) that some languages are stuck with poor or archaic translations. But in English, at least, we should be grateful that we do have multiple accurate, useful, sound English Bible translations done by competent Christian scholars.

Assuming that one translation must be the “most accurate” has led many Bible readers on a fruitless and frustrating quest. And when it comes to the King James Version, it must be pointed out that “accuracy” is a moving target, because language (as C. S. Lewis once said, actually) “is a changing thing.” The King James was an accurate translation, but it was made into an English no one speaks anymore. Those who love the KJV—some of whom insist that it is the only translation anyone should use—give testimony to this when they make archaic KJV word lists to help contemporary readers. I say with biblical scholar Glenn Scorgie, “If a translation is published but fails to communicate, is it really a translation?” Wherever the KJV uses English that is no longer in use, the KJV is, in a very real sense, “inaccurate.” It doesn’t get God’s message across. (See my forthcoming Lexham Press book, KJV Words You Don’t Know You Don’t Know.)

What is the best translation of the Bible and why?

Check with me on Mon-Wed-Fri, and I’ll say, “The best Bible translation is the one you will read”; check with me on Tues-Thurs-Sat, and I’ll say, “The best Bible translation is all the good ones”; check with me on Sunday, and I’ll say, “Shh! I’m in church! I’m happy to use whatever translation my pastor is preaching from.”

God has not anointed one translation over others. Perfectly word-for-word translations are impossible. So I believe that we all need to see the benefits of our multi-translation situation. I believe—and do please help my unbelief, folks!—that normal people in Christian churches should regularly benefit from checking several major modern English Bible translations. Users of Logos Bible Software very frequently do this; many other Christians do not. And I think this is a significant Bible study mistake.

My family loves to listen to the King’s Singers, and they occasionally sing some old pop standards—including Billy Joel’s “Uptown Girl.” My second-grader recently revealed that he instead thought they were singing, “Up-Down World.”

This is the kind of thing that will happen to your Bible reading if you don’t check multiple English Bibles. You’ll fall into little mental ruts without the remotest realization. It will take checking the NIV to realize, “Oh! It’s the boundary lines around David’s plot of land that have fallen for him in pleasant places!” If you read multiple translations, you will have this embarrassing but delightful experience many times.I cannot choose one translation as The Best, precisely because I so love to hear from people, “Ah! So that’s what that means!”

Which Bible translation is closest to the original?

When people hear me say that there is no “best” Bible translation, I think they sometimes panic. Who is this strange redheaded contrarian who dares to cast doubt on my important quest to find THE ONE RING TO RULE THEM ALL? They have trouble dropping the idea that, surely, one translation must be more closely tied to the original Hebrew and Greek than any other. After all, the marketing slogans—“Essentially Literal”; “The Most Literal; Still Readable”; “Know What God Said, Not What We Think He Said”—promise so much!

I say gently: listen to yourself, my friend! You just cited marketing slogans. Marketers gotta market; I grant this. (I also grant that I put words in your mouth . . .) But I must carefully encourage all English-speaking Christians to take advertisements with a grain of that gold dust they use to gild Bible pages. God gave us a situation in which it is pretty easy, honestly, to communicate the message of the inspired Hebrew and Greek originals. All good translations do it. And it is possible to get little individual things “wrong” in a Bible translation; I, who have graded student exegesis papers, do not deny this. But I have spent many years reading and comparing all the major modern evangelical English Bible translations—the KJV, NKJV, LEB, CSB, ESV, NASB, NIV, NLT, and others—and they are all close to the originals. None is the obvious victor. And even if one were, I would still see plenty of use for the others.

Is the NKJV Bible accurate?

The NKJV Bible is an accurate Bible translation made by competent evangelical biblical scholars. It also has a helpful feature for those who like to get nerdy about Bible study: it includes little “textual notes” in the margins mentioning places where the manuscript tradition of the Greek New Testament has what are called “variants”—minor differences in spelling or wording that were introduced before the era of printing made it possible for books to be mass-produced rather than having to be hand-copied.

Every Bible translator has to do something with these variants. Even though the vast majority of the text of the New Testament is in no doubt, and even though these variants are typically incredibly minor (and often enough not even translatable into English), these variants can’t be ignored or dismissed. The King James translators long ago looked at them, and they left notes about them in the margins of the KJV. When they chose the ancient manuscripts that said, “Shew me thy faith without thy works” over the ancient manuscripts that said the opposite (“Shew me thy faith by thy works”), the KJV translators in effect created a tradition—one the NKJV followed.

The margin of the 1611 KJV recognizes that “Some copies [of the Greek New Testament] reade” differently than others at James 2:18.

This does mean that the NKJV follows tradition even in places where modern scholars, with access to far more information than the KJV translators had, make different decisions about the variants; so the NKJV is not generally used among biblical scholars. But those scholars will be the first to tell you that the differences amount to very little of substance. The NKJV is still an excellent and worthwhile evangelical English Bible translation.

Is the ESV trustworthy?

The ESV was created by competent evangelical biblical scholars who worked hard to revise the widely respected—but just as widely distrusted—Revised Standard Version, which was a revision of a revision of the King James.

Bible translations live and die based on public trust. Some good translations never win that trust. Some win a bit too much. The King James Version is such a one. It was an excellent translation, but it came to command so much veneration that even when its language—because of the natural and inevitable process of language change—started to be misunderstood by the common people for whom it was made, there was little to no call for it to be revised or replaced. Ben Franklin in the 1770s and Noah Webster in the 1830s both noticed that the English of the KJV had become antiquated. Webster actually commented (in his own revision of the KJV) that not only had some words in the KJV fallen into disuse, but some had shifted in sense and had become positively misleading. I talk a great deal about this in my book Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible.

If you, like nearly all English speakers over a certain age, grew up with the King James Version, and if you are now looking for a good translation into contemporary English, it might be useful for you to pick up the ESV. The ESV is a relatively minimal update within the KJV tradition. Like the NKJV, the ESV sticks fairly closely to the wording of the KJV but updates the English. Unlike the NKJV, the ESV incorporates insights from the modern study of the ancient manuscripts of the Hebrew Old Testament and Greek New Testament.

Crossway, the nonprofit ministry behind the ESV, has a special reputation for producing elegant and useful print editions of their Bible version. The ESV has been for over two decades a favorite among serious Bible students.

Is NLT or NIV better?

If you, like I, grew up using a more formal (or “literal”) English Bible translation like the KJV or the NASB, the best thing to ease you out of any Bible-reading ruts you are in may be to look for a less formal/literal translation such as the New Living Translation or the New International Version.

The NIV is considered a middle-of-the-road translation. If every translation is a balancing act between more formal and more functional (or “dynamic”) translation decisions, the NIV stands between the two poles with a firm grasp on each. The New Living Translation, meanwhile, leans more toward the functional pole.

So the NIV reads smoothly for modern English speakers; the NLT reads very smoothly. I think the NIV is a great default choice for churches, especially if they don’t know in advance who they’ll be serving. But when I was an outreach pastor, I did know who I was going to be serving: functionally illiterate adults. For them, the New Living Translation would have been more appropriate than the NIV (though as it happened, I ended up choosing a special version of the NIV made for poor readers called the New International Reader’s Version). I do remember once, too, preaching at an evangelistic youth event that was evenly split between church kids and kids with no church background, and I reached for the NLT for help communicating an important idea in Romans to people with no background in the Bible.Neither the NLT or NIV is “better” than the other. You have to ask, “Better for what?” The NIV is better for certain circumstances and certain audiences; the NLT is better for others.

What is a good Bible to read and understand?

The late atheist Christopher Hitchens once wrote an article for Vanity Fair in which he bemoaned the decline of the King James Version and the rise of custom-made “Bibles.” He cited “the ‘Couples Bible,’ ‘One Year New Testament for Busy Moms,’ ‘Extreme Teen Study Bible,’ ‘Policeman’s Bible,’ and … the ‘Celebrate Recovery Bible.’” Hitchens had a way with words (in other news: the pope is decidedly Catholic), and he complained that “in this cut-price spiritual cafeteria, interest groups and even individuals can have their own customized version of God’s word.”

In his mind, these were apparently wholly different Bibles tailored for certain audiences. But they weren’t. They were study editions whose notes were aimed at certain audiences. This is an important difference. I acknowledge that I may sometimes roll my eyes at evangelicalism’s too-zealous efforts to make the Bible accessible, even at the risk of cheesiness and hokiness. But the fact is that every one of the editions Hitchens named could have come out in the same translation—the NIV, the NKJV, or even the KJV.

We must not equivocate with this word “Bible.” There is only one Bible. It is the best Bible to read and understand. Every major modern translation does its best, with slightly different philosophies and emphases, to communicate the truth of this one Bible. So whatever Bible you have nearest at hand is almost certainly the best one to read and understand. And if you struggle to understand it, try another translation (not another “Bible”).And keep trying. The Bible is worth all the study effort you throw at it. I say about Scripture basically what Paul said to Timothy (2 Tim 2:7): Think over what God says, and the Lord will give you understanding in all things.

How do I choose a Bible translation?

How do you choose a Bible? I’m not kidding: the last time someone asked me that question—which, as I write, happens to have been yesterday—I said, “Flip a coin.” I wasn’t being flippant (no pun intended). I was trying to make a point: unless the Lord translates the Bible, they labor in vain who search for “the best” Bible translation (my apologies to Psalm 127:1).

I’d like to add some more initially-inane-sounding advice to those wanting to know which Bible translation is best: chill out; calm down; it’s ok! It’s difficult to go wrong!

The English Bible translations I know well are the 1) major 2) modern 3) evangelical ones. I can speak with confidence, then, of the NKJV, CSB, ESV, NASB, NIV, NET, and NLT. They’re all good. Choose one. Roll a dice instead of flipping a coin if you have to. Of each one of them I can say what the KJV translators said (and here I again paraphrase):

Even the worst English Bible translations available contain—no, they are—the word of God. When the king speaks, the speech he delivers is still his speech even after it gets translated into French, Dutch, and Italian—and even if certain translators are not as graceful as others. We judge something by its predominant character, not by its exceptions. A handsome man is not considered to have lost his good looks simply because he has a few warts on his hand.

Every translation has warts: sentences that are inelegant or unnecessarily difficult or not as technically accurate as they could be. But the predominant character of every 1) major 2) modern 3) evangelical Bible translation is the same. Every one is the word of God—the word of God translated. Read this book by Dave Brunn to gain a basic sense for how the formal/literal ones differ somewhat from the functional/dynamic ones, yes. The major translations are substantially similar but usefully different.

But then pick one and read it. Next year pick a different one and read it. Next time you dig into a Bible study, pick several and read them all with the Text Comparison Tool in Logos Bible Software. We have an embarrassment of riches in English Bible translation. Take up and read; go and spend those riches.

***

Related articles

- How to Choose a Good Bible Translation: 5 Guidelines

- Why Is This Passage Omitted from Some Translations and not Others?

- Compare Bible Translations as You Study (Logos training article)

- What Is Textual Criticism? And How Is It Different Than Translation

- John D. Barry, Lexham Bible Dictionary (Lexham Press, Bellingham, WA) 2016.

- https://www.wycliffe.net/resources/statistics/

- Ron Rhodes, The Complete Guide to Bible Translation (Harvest House Publishers), 2009.

- Rhodes, The Complete Guide, 2009.

- Ryken, The Word of God in English, 48.

- The Great Bible was large—it’s pages measured 15 X 10 inches, making it the biggest Bible printed to date.

- Leland Ryken, The Word of God in English (Crossway Books, 2002), 48.

- Mark Ward, “How to Choose a Bible Translation That’s Right for You.” Bible Study Magazine (Lexham Press, Sept/Oct 2019), 39.

- Ward, “How to Choose,” 39.

- Ward, “How to Choose,” 36.

- Dave Brunn, One Bible, Many Versions: Are All Translations Created Equal? (InterVarsity Press Academic, 2012), Ch. 9.

- Brunn, One Bible, Ch. 9.

- Brunn, One Bible, Ch. 9.

- Brunn, One Bible, Ch. 9.

- Ward, “How to Choose,” 39.