A former coworker of mine, now retired, a very sharp editor and faithful Bible reader, sends me occasional Bible questions. She sent one the other day about the alleged secret meaning of God’s name:

Hey, Mark, I’ve seen this circulating on social media and wonder if this is how Hebrew works.

My friend continued:

I’ve never heard this meaning before. Do you define the word by the individual meaning of the letters? If so, how does this meaning square with Exodus 3:14? Thanks!

Secret meaning

I love these questions. And I have some guidance for those who run across such memes.

Anytime I encounter claims about secret meaning in the Hebrew or Greek, especially those employing some kind of apparently consistent linguistic method, I like to see where that method takes me. If it takes me to consistent insight, and insight that persuades other judicious interpreters, then it probably reflects something about how God made language or how he inspired the Bible. If it takes me to greater and greater absurdities … perhaps I can at least get an article out of it for Word by Word.

So let’s try this method. Under the rules as stated, the meaning of YHWH would actually be, “Hand behold nail behold” (where did the source get the “my” and the “the”?).

But then the “true meaning” of other words that contain these letters would also be some mixture of “hand,” “behold,” and “nail.” For instance, by this method, the very common word וַיְהִי (WYHY), which usually gets translated, “And it came to pass,” or sometimes just “when” (sometimes it’s not translated at all), would mean “nail hand behold hand.”

And those three letters aren’t the only ones in the Hebrew alphabet: the method can be extended, presumably. The internet tells me what the other Hebrew letters “mean,” so now we can know the secret meaning of all the words in the Hebrew Bible!

- By this method, another major title for God, Adonai (usually translated “lord” or “master”), has the secret meaning, “Ox door serpent hand”—or perhaps, because possible alternate meanings are given for each letter at Wikipedia, “Cow head fish fish hand.” And if you think about it long enough, you can probably come up with some way for that to picture Jesus. If it’s ox-door-serpent-hand, you can imagine an ox trying to enter the door to the sheepfold of the kingdom, but the hand of the serpent stops him. Or if it’s cowhead-fish-fish-hand, you can think of, um, a barley loaf in the shape of a cow head and two small fishes in the hands of the little boy who shared his meal, enabling Jesus’ miracle of the feeding of the five thousand (??).

- The longest Hebrew words are the best: you can get the most meaning out of them. The name “Hazzelelponi,” a descendant of Judah (1 Chr 4:3), really meant something like, “There’s a papyrus plant in the window—goad yourself, goad yourself with the fish hook in your hand.” This, too, has deep theological meaning. The papyrus, of course, was the main kind of paper used for making early copies of the Greek New Testament, so I think the name Hazzelelponi was probably a promise that that the New Testament would soon be seen—it was in the window, as it were. And if the ancient Israelites would just have goaded themselves to study, to the point of sharp physical pain, they’d have seen that papyrus—they’d have known that the Messiah (which really means “water sun hand wall”) was coming.

- But there’s something even better than long words. This method works equally well with whole verses, too—and why not, if we can do it with words? Under this method (and if your source gets to add connector words, so do I), Genesis 1:1 really means: “The house’s head ox had a tooth in his arm—marked with a house head ox, in fact. And an ox goad in the window had a hand on the water ox. But, mark well, the window tooth also had a water arm, a water hook, and an ox mark window. Ox heads are papyrus plants.”

Absurdities

I think we’re discovering greater and greater absurdities. There is also a significant complication here called matres lectionis, consonants that are used to indicate particular vowels but were likely not present when Moses actually sat down to put pen to parchment using, we presume, some kind of paleo-Hebrew script. In other words, the exact original spelling of some Hebrew words was probably a bit different than what we see in the Hebrew Bible today.

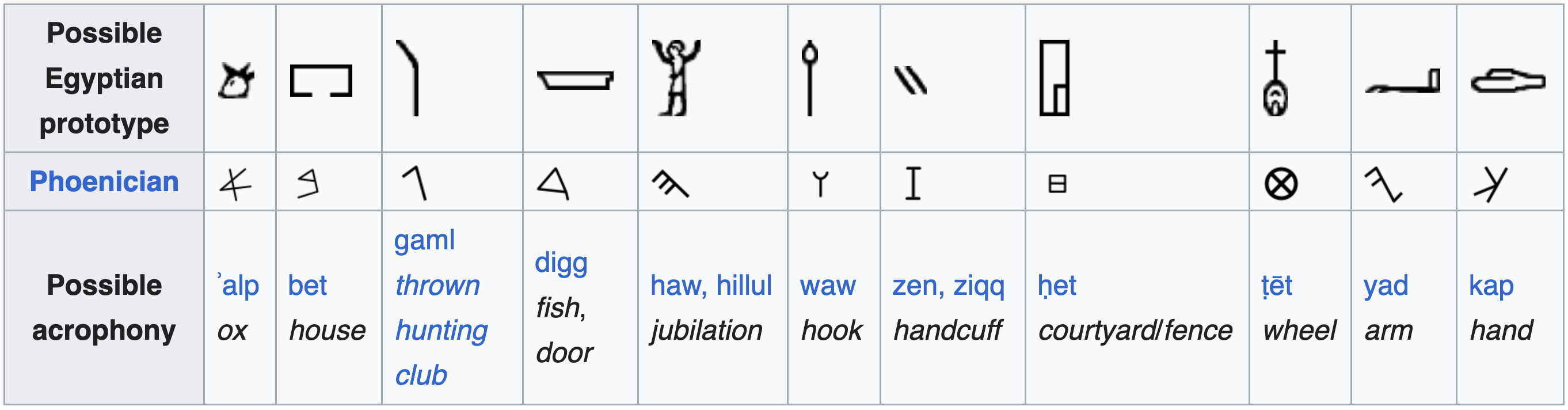

I’ll confess now the weakest point of my answer: I don’t know for certain where the conventional associations named in that meme actually come from. I assume they have at least a partial basis in fact, because indeed it is widely accepted that Hebrew (and Greek, for that matter) alphabets have their ultimate source in pictograms/ideograms.

But we’ve got precisely zero indication that the authors of the Hebrew Bible had any of those historic associations in mind—anymore than we today think about the palm of the hand when we write out the letter K.

Indeed, why shouldn’t this method work in English?

I’ll tell you why: if my wife wrote me a Post-it Note and stuck it on the fridge, with some text saying, “Please take out the trash,” and if I spent fifteen minutes figuring out the secret meaning supposedly invested in every letter instead of taking out the trash, my wife would be mad.

I think God is not pleased by the herculean efforts some people go to look so hard for hidden meanings—whether linguistic or allegorical or what have you—that they miss the simple point of what he said. Bible interpretation is hard enough without layering on top of it all kinds of linguistic silliness.

Exodus 3:14

My old coworker’s reference to Exodus 3:14 is on point: God had a chance to tell us the meaning of his name, and that’s the closest he chose to come. She, in fact, had come up with an excellent example of doing just what I always recommend: if someone makes an interpretive argument based on the alleged meaning of a Hebrew or Greek word, an interpretive argument you (by definition) can’t verify from your English translation, look instead to sentences—sentences you can read in English. If a sentence or paragraph or narrative bears out the argument, you’re good. But frequently it won’t. God’s word in translation is not hiding essential information, or he would have called us all to learn Hebrew and Greek.

If there are layers of meaning in the Hebrew that aren’t available in English, the way to find them is to check multiple English translations. They do sometimes help you see shades of meaning in difficult words—like the paraclete of John: is he a comforter, a helper, an advocate? Probably yes.

But if you compare translations at Exodus 3:14, you’ll find that the translations are pretty united. God chose to give an ambiguous, veiled, layered answer, and no respected translations really make it clearer.

Then Moses said to God, “If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I AM WHO I AM.” And he said, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘I AM has sent me to you.’ ” (Exodus 3:13–14)

I’m not saying knowledge of Hebrew is irrelevant to the study of this puzzling statement from God. But it’s a help mainly at the technical level. I do expect people to be able to get a sound interpretation out of this verse even through translation alone. The themes of authority and divine aseity (the idea that God exists by himself and to himself without any dependence on others) that most interpreters see in the Hebrew are just as visible in English. Honestly: I don’t think Moses understood God at the burning bush with anymore clarity than we do now, especially given the subsequent history of Abraham’s seed that we know and he didn’t—not to mention our centuries of reflection on the famous and glorious passage we know as Exodus 3.

My advice

My advice: keep reading and reflecting on the English, and if the Hebrew really has something to say that you can’t see in English, it’ll probably be in the notes in a good study Bible—or, certainly, in a good commentary in Logos.

If it’s not, you can move on to lexicons—Logos has plenty of good ones (try CHALOT for Hebrew, BDAG for Greek)—or to the Lexham Theological Wordbook.